Taking control of RBS

People-powered banking that puts communities first

22 October 2016

Eight years on from the financial crisis, RBS is still failing its customers and its owner – the UK public. Taking control of RBS and turning it into a network of 130 local banks would help rebalance the economy by investing in communities and businesses left behind by our London-centric economic model.

1. The urgent need for a new economy

The UK’s vote to leave the European Union exposed deep underlying regional divides. Research conducted since the referendum has found that geographical distribution of living standards played a key role in determining how people voted. Part of the reason for this can be found in the UK’s notoriously uneven economic landscape.

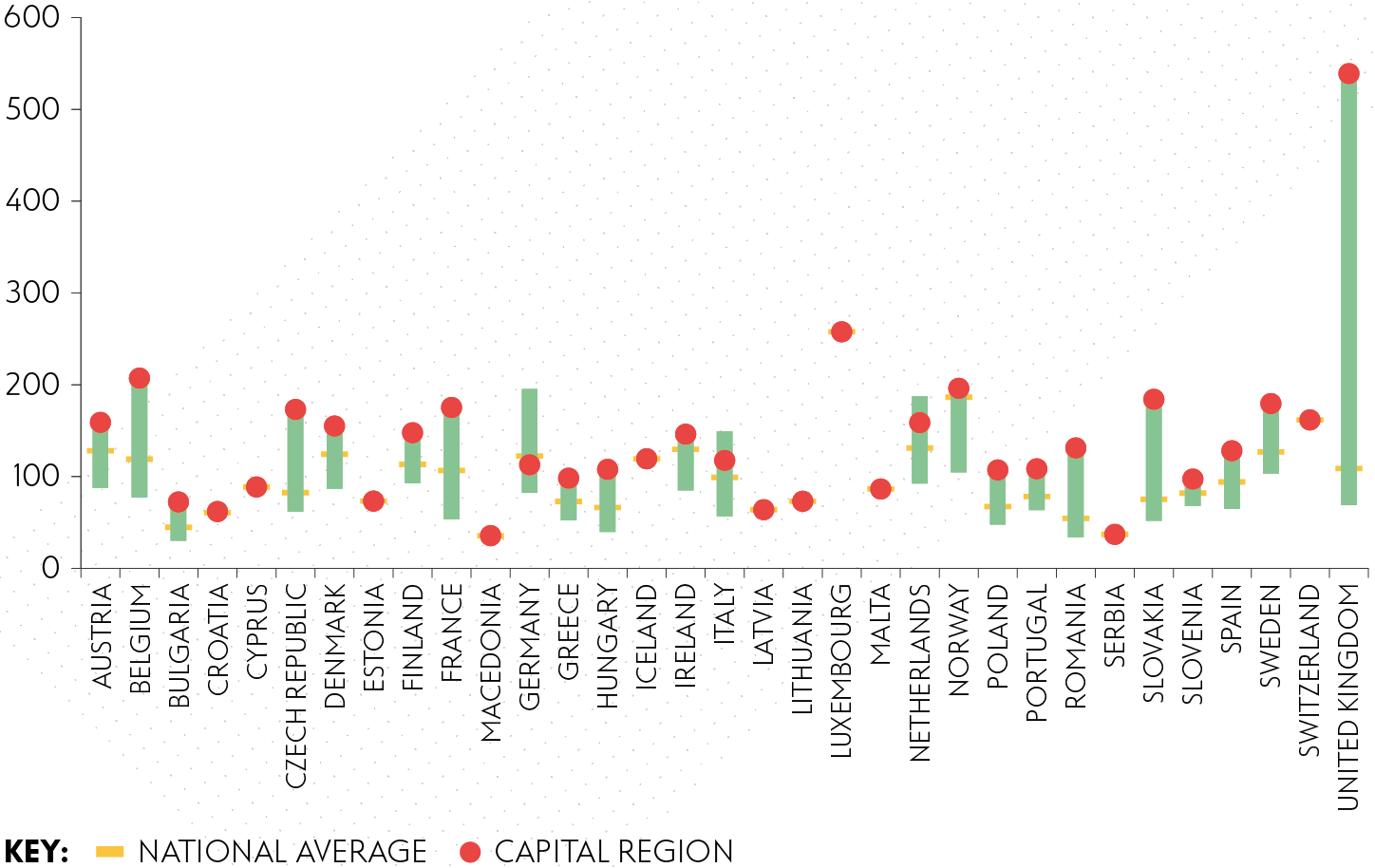

Figure 1 shows the distribution of output within each EU member state, shown as the spread between their poorest region and their richest. The UK is clearly the most geographically unequal country in the EU. Inner London is the richest single area and sits at the top of the UK’s line, but West Wales and The Valleys, the region at the very bottom of the UK’s graph, is poorer than some recent EU accession countries.

Figure 1: Regional disparities in GDP per capita by EU member state, 2013/14 (EU28 average = 100)

Source: Eurostat

The result of EU referendum can be viewed as an expression of this economic polarisation, with some describing the outcome as a vote “against the London economy”.

“The last few decades have seen this gap increase as growth has been driven by financial services in London and the South East while many communities have been left behind by a decline in British industry.”

On current trends, things are likely to get worse. Many of the communities that voted to leave have also benefitted the most from EU regional development funding, meaning that they stand to lose the most from leaving. There is therefore an urgent need to rebalance the economy and promote sustainable economic development in areas that have been left behind by our London-centric economic model.

2. Communities left behind by our global economy

The growing polarisation of the UK economy has been accompanied by significant transformation in the landscape of the financial sector. A wave of mergers and consolidation in the late 1960s and early 1970s saw the UK banking sector become increasingly concentrated. This was further accelerated by legislative changes in the mid-to-late 1980s which led to the decline of Building Societies as a significant component of the overall banking market.

Image credit: Malcolm Payne via Flickr

One example of this can be seen with the fate of the Trustee Savings Banks. In 1976, 20% of the UK population had an account at a Trustee Savings Bank and yet by 1986 the sector had been transformed into a single national shareholder bank. In 1995 it finally disappeared in a merger with Lloyds Bank.

Meanwhile, waves of deregulation beginning in the 1970s led to rapid growth in financial sector activity and profitability. The share of total profits absorbed by financial corporations, having been very low at around 1% through the 1950s and the 1960s, grew substantially from the early 1980s to the present day, reaching 15% after the financial crisis.

The result of this is that the UK now has among the largest and most concentrated banking sector in the advanced economies, with the top three banks owning over half of all bank assets.

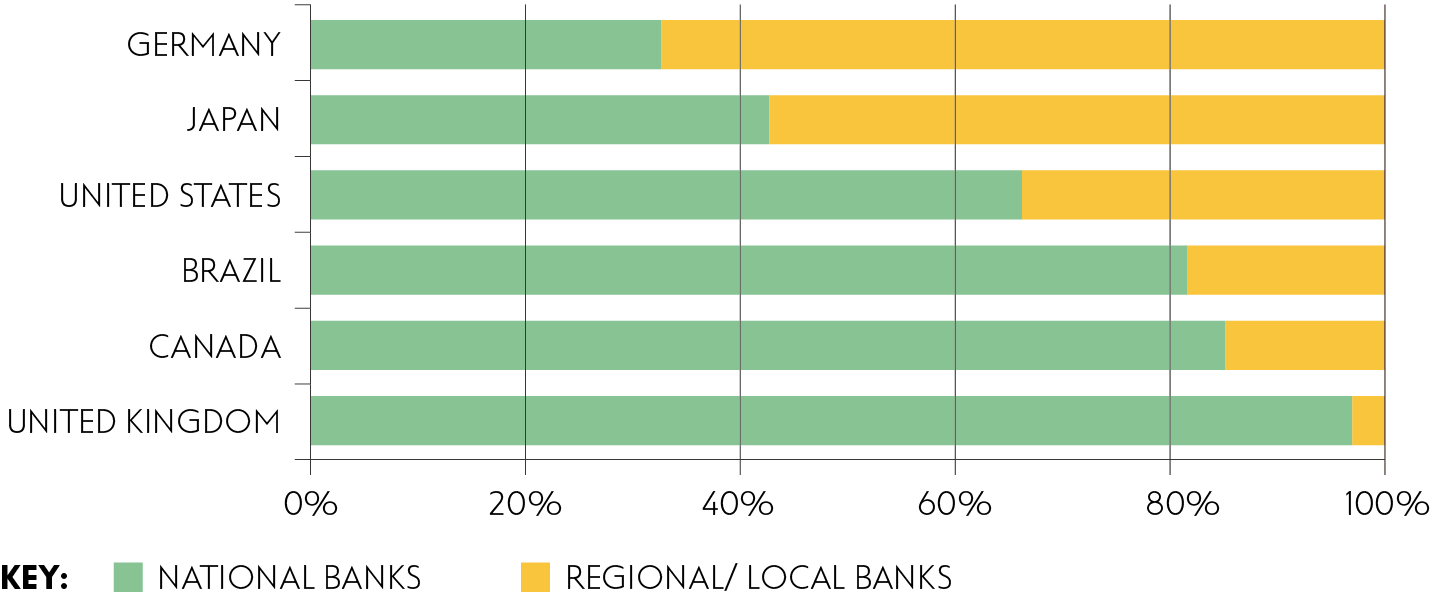

Figure 2: Banks’ market shares of deposits by geographic scale

Source: New Economics Foundation

The UK is also unusual in that it lacks a significant local or regional banking presence – the market is overwhelmingly dominated by national and often internationally orientated banks. Approximately 67%, 57% and 34% of the banking systems in Germany, Japan and America respectively are locally controlled, compared to just 3% in the UK (see Figure 2).

In other countries local banking sectors play a key role in promoting local economies, and these banks are often characterised by stakeholder ownership and governance – in other words the mission of the bank is not to maximise profits but to optimise returns to a range of stakeholders, including customers and the broader local economy. These often take the institutional form of co-operatives, mutuals and public savings banks.

Empirical studies from European counties have shown that geographically-limited stakeholder banks help reduce ‘capital drain’ to urban centres and thus regional inequality, and other studies have shown that such banks direct a much greater proportion of their capital towards real economy lending. Local sources of finance are often an important determinant for economic development by creating and retaining wealth regionally rather than reinforcing existing geographic lending imbalances.

In contrast, UK banking is dominated by large corporations whose main aim is to maximise shareholder return.

Image credit: Adrian Scottow via Flickr

Without a focus on specific geographical areas or social objectives, these banks choose to allocate their capital to the most profitable activities, and lending to local businesses – often involving high transaction costs for relatively small loans – is less profitable than other activities such as mortgage lending and lending to other financial institutions.

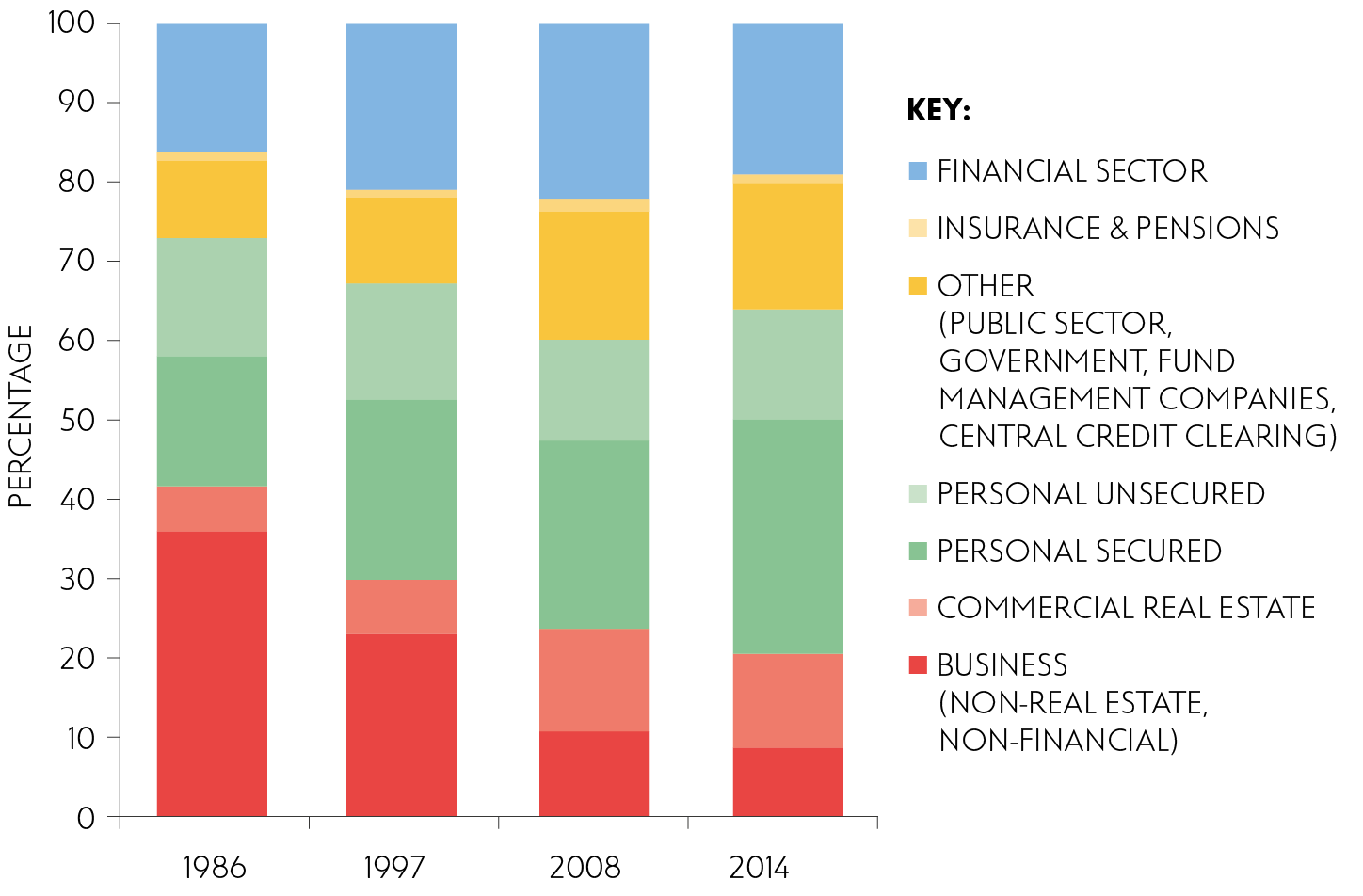

The result is that since the mid-1980s the share of lending going to businesses has been falling rapidly, and now represents less than 10% of total lending (see red colour in figure 3). Meanwhile, lending to financial institutions for speculative trading has boosted the profitability of the City, and a rapid increase in mortgage lending has contributed towards a boom in house prices which are now nine times average incomes across England and Wales, and up to 20 times incomes in London and the South East.

Figure 3: UK domestic banks – composition of net lending by industrial sector

Source: New Economics Foundation

Of the business lending that does occur in the UK, most is heavily concentrated in London and surrounding areas. According to the most recent available data, 33% of SME lending goes to London and the South East compared to just 8% to Scotland, 5% to Wales and 3% to the North East.

By leaving many regions on the wrong side of the UK’s finance-led economy, the UK’s homogenous and highly concentrated banking sector has contributed towards a lack of productive investment and growing regional imbalances. Re-establishing local and regional sources of finance should therefore be a key priority in addressing these acute regional imbalances and promoting economic renewal across the country.

3. RBS: the old model and a record of failure

As a result of the emergency bail-out package in October 2008, the British public acquired a majority shareholding in RBS at a total cost of £45.5 billion. In August 2015 the Government conducted its first RBS share sale since the financial crisis, disposing of a 5.4 per cent stake which raised £2.1bn of proceeds and left the UK government with a 73% stake in the company.

In recent years RBS has undergone major restructuring in an attempt to refocus on its core business. In April 2014, RBS announced a new strategy to focus on UK retail banking and simplified its structure, grouping its activities into three distinct businesses. It has also sold its US bank, Citizens Financial Group, and has transferred high risk assets into a so-called bad bank – RBS Capital Resolution. In order to comply with conditions attached to the bail-out in 2008, RBS also attempted to launch Williams & Glynn – a bank with 314 branches, approximately £20 billion of loans and £22 billion of customer deposits – as a new challenger bank.

However, after years of expensive delays RBS recently announced that it had abandoned plans to launch it as a new standalone bank and will instead seek to sell the assets and branches to a rival. Previously the government has used the spin-off of Williams & Glynn as an argument against reforming RBS, stating that the creation of a new challenger bank will improve banking diversity through new “challenger branches”. While this argument was always flawed, confusing local branches with local banks, it is clear that with Williams & Glynn now being sold to a rival this reasoning is no longer valid. In September 2016 it was revealed that HM Treasury drafted in Rothschild investment bank to help speed up the sale process.

Despite this restructuring, RBS has struggled to improve its performance. The company has run eight successive years of losses amounting to a total of £50 billion, and despite repeated pledges to improve customer satisfaction, RBS was ranked bottom out of more than 30 banks for customer satisfaction in a recent survey carried out by consumer group Which?.

RBS Global Restructuring Group

In the wake of the financial crash more than 12,000 companies were pushed into the bank’s controversial “turnaround” division – the so-called Global Restructuring Group (GRG). This division has become notorious for its behaviour towards SMEs and has for years been accused of deliberately pushing businesses towards insolvency in order to shore up RBS’ own capital position, in some cases then buying up their assets cheaply.

These accusations have now been substantiated by internal leaked documents that were published by BuzzFeed News and BBC Newsnight on 10 October 2016. The documents show that bank employees were rewarded with higher bonuses based on fees collected for “restructuring” business customers’ debts – cutting the size of their loans and getting cash or other assets from the customer. In what was described by one RBS executive as “Project Dash for Cash”, employees were asked to seek out companies that could be restructured or have their interest rates increased. Where business customers had not defaulted on their loans, bank staff were encouraged to find a way to “provoke a default”.

Many business owners say that unrealistically low valuations were used to claim they had breached their loan covenant or terms of business and force them into the GRG. In many cases the bank then sought to impose higher interest and fees, pressure customers to sell assets to pay down loans or push the business into administration to enable asset stripping.

“Many of the small business owners affected say they have not only lost their businesses but also experienced family break-ups and deteriorating physical and mental health due to the stress of their treatment at the hands of the bank. Others have been made homeless or bankrupt.”

In light of these revelations, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has been urged to publish its long-awaited but repeatedly delayed investigation into the GRG. A group of 500 businesses are suing RBS for the conduct of the GRG and is also threatening legal action against the FCA if it does not immediately publish its report into the scandal.

Conduct and litigation charges

Since the financial crisis RBS’s financial performance has been weighed down by extensive conduct and litigation charges relating to gross misconduct at the bank. According to the CCP Research Foundation, between 2011 and 2015 RBS paid out £14.7 billion in fines, legal bills and customer compensation. These charges relate to litigation and investigations covering a range of activities including securitisation and mortgage-backed securities, foreign exchange trading and rate-setting activities, London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) fixing, product mis-selling (including mis-selling of Payment Protection Insurance), treatment of SME customers in financial difficulty, and money laundering. Many of these investigations are still ongoing – including a substantial case being pursued by the US Ministry of Justice – and it is likely that future conduct and litigation charges could be substantial.

Branch closures

In recent years the large UK banks have embarked on major programme of branch closures in an attempt to cut costs in the face of downward pressure on profits. In 2014 and 2015 alone 1,150 branches were closed across the UK.

Image credit: Kake via Flickr

RBS has been most aggressive in its programme of branch closures, being responsible for 385 of these closures – one in every three. Despite promising in 2010 to “never to close the last bank in town”, 165 of these closures were the last branch in town – accounting for around half of all such closures in the UK. The result is that there are now 1,500 communities across the UK with no bank and another 840 with only one bank remaining, leaving many vulnerable customers and businesses without access to essential services.

As well as increasing the risk of financial exclusion, bank branch coverage is important for SMEs – not only as a means to carry out essential transactions, but also because evidence suggests this may be a factor in the geographical distribution of lending. Research conducted by Move Your Money found that branch closures have been associated with a decline in business lending, with SME lending growth falling by 63% on average in postcodes that lost a bank branch, increasing to 104% for postcodes that lost their last-bank-in-town.

“Worryingly, RBS appears to be closing branches in communities that need them most, but opening new branches in affluent urban areas.”

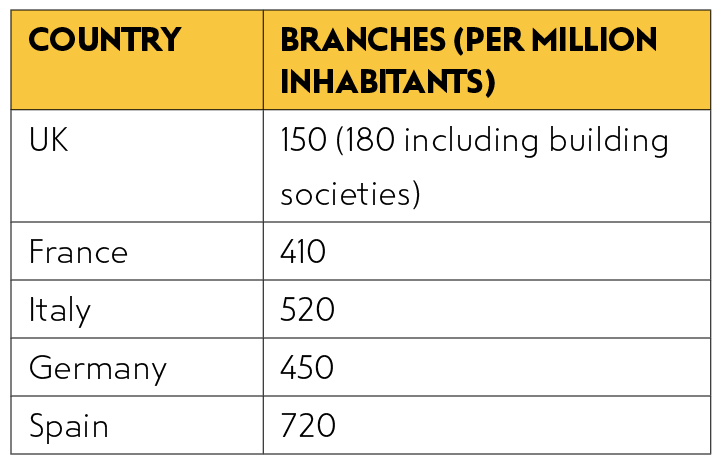

This year alone, RBS has closed over 100 branches in predominantly rural and non-affluent areas, whilst opening new branches in the prime real estate locations of Canary Wharf and Bishopsgate – changes that will act to reinforce existing geographic lending imbalances. The result is that the UK now has only a third as many bank branches per person as other European countries. If these trends are allowed to continue unchecked, SMEs will find it even harder to access finance and basic banking services.

Table 1: European comparison of bank branches

Source: Campaign for Community Banking Services

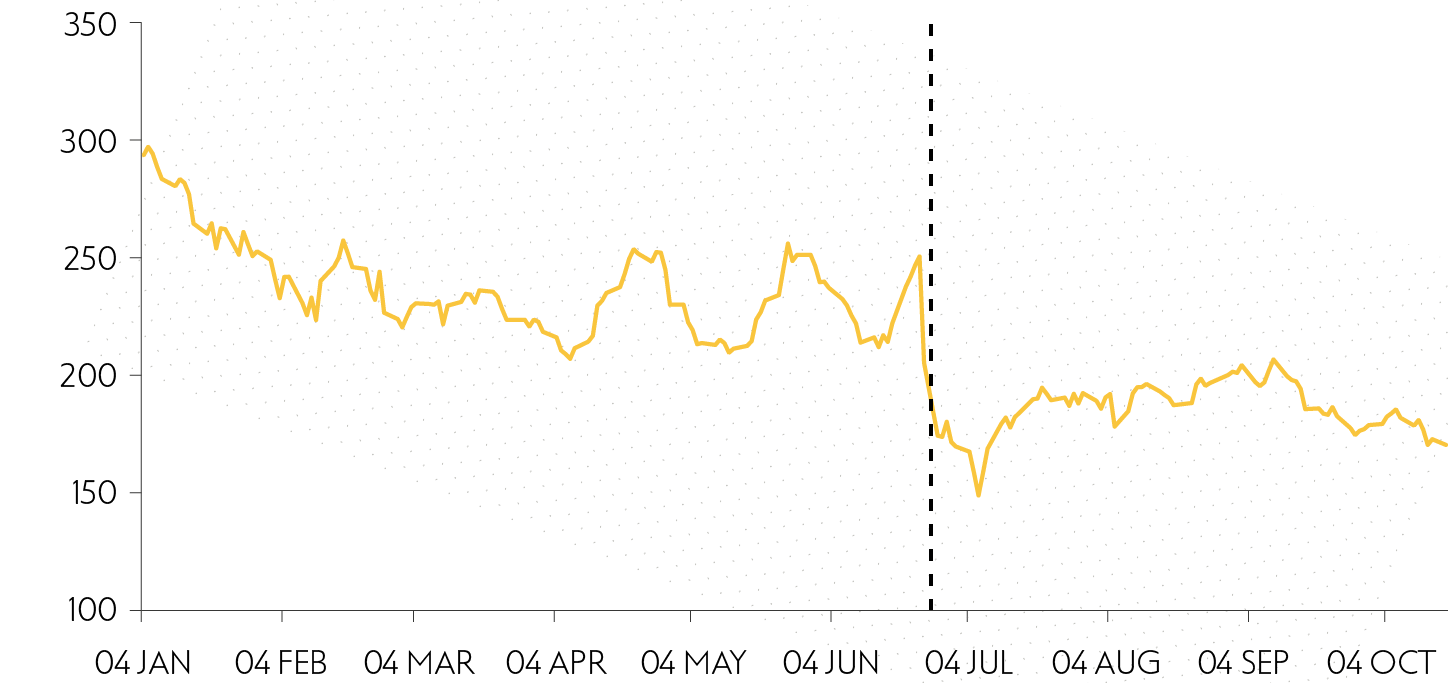

Share price

Despite the UK government’s initial claim that it would not sell RBS at a loss, it is becoming increasingly clear that there is no way the taxpayer can make its money back by selling RBS back to the private sector. Following the result of the EU referendum the RBS share price fell to its lowest level since the collapse of 2009, causing shares to be temporarily suspended from trading (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Royal Bank of Scotland share price in 2016 (dashed line = EU referendum)

Source: Yahoo Finance

Using the methodology that the Foundation published in 2015, selling the government’s remaining 73% stake in RBS would yield around £15 billion, resulting in a loss to the taxpayer of an eye-watering £30 billion. On 18 October the Financial Times reported that the Office for Budget Responsibility is preparing to once again revise up its forecast on the likely losses on the taxpayer’s stake in RBS as part of the Chancellor’s Autumn Statement, creating a £7bn hole in plans to reduce the level of public debt.

Both the Treasury and RBS now acknowledge that the bank cannot be sold in the foreseeable future and have delayed the sale for at least another two years.

4. Taking real control of RBS

Eight years after the financial crisis, it is clear that RBS is still not delivering for customers or its owner – the UK public. With it now being clear that RBS cannot be sold in the foreseeable future, it’s time for the government to put all options for the bank’s future back on the table and urgently examine whether there are alternatives that could deliver better value for taxpayers and the economy.

As we set out in our report ‘Reforming RBS: Local banking for the public good’, transforming RBS into a network of 130 local banks with a public service mandate and supervised by citizen stakeholders would transform the face of UK domestic retail banking and bring significant economic benefits.

The key features of our proposal are as follows:

- The government should purchase the remaining minority interest shares in RBS to take complete control for a transitionary phase.

- The Corporate & Institutional Banking and Private Banking divisions should be divested, and the capital realised used to repay the cost of buying out the minority interest and to bolster the bank’s capital position.

- The bank would be separated into 130 local banks in England, based on local authority areas and subject to consultation.

- The degree of decentralisation for the Scottish and Welsh parts, and Ulster Bank, would be a matter for their respective national governments.

- The local banks would operate as a network, with a mutual guarantee scheme based on the German savings bank model.

- Central functions such as IT, training, marketing, regulatory compliance, public affairs, liquidity management, and specialist financial services would be retained in a group entity jointly owned by the member local banks.

- The new local banks would be retail banks focused on households and local businesses, including social enterprises and charities.

Public service mandate

Each new local bank would have a public service mandate to serve the common good by the provision of financial services according to the following principles:

- to restrict its activities to the geographic region in which the enterprise is domiciled;

- to conduct the bank’s business so as to benefit the economy of the region;

- to promote positive attitudes to saving and to advance financial literacy;

- to provide access to basic transactional banking services to all citizens regardless of income, wealth, or social status;

- to provide access to personal credit on fair and affordable terms;

- to support private, social, and public enterprise through the provision of appropriate financial products and services, including advice;

- to manage the bank’s capital prudently; and

- to earn sufficient profits to grow the bank’s capital, to maintain its commercial vitality, and to invest in the delivery of its objectives. Although the bank will aim to generate profits, but this is not the primary purpose of the bank.

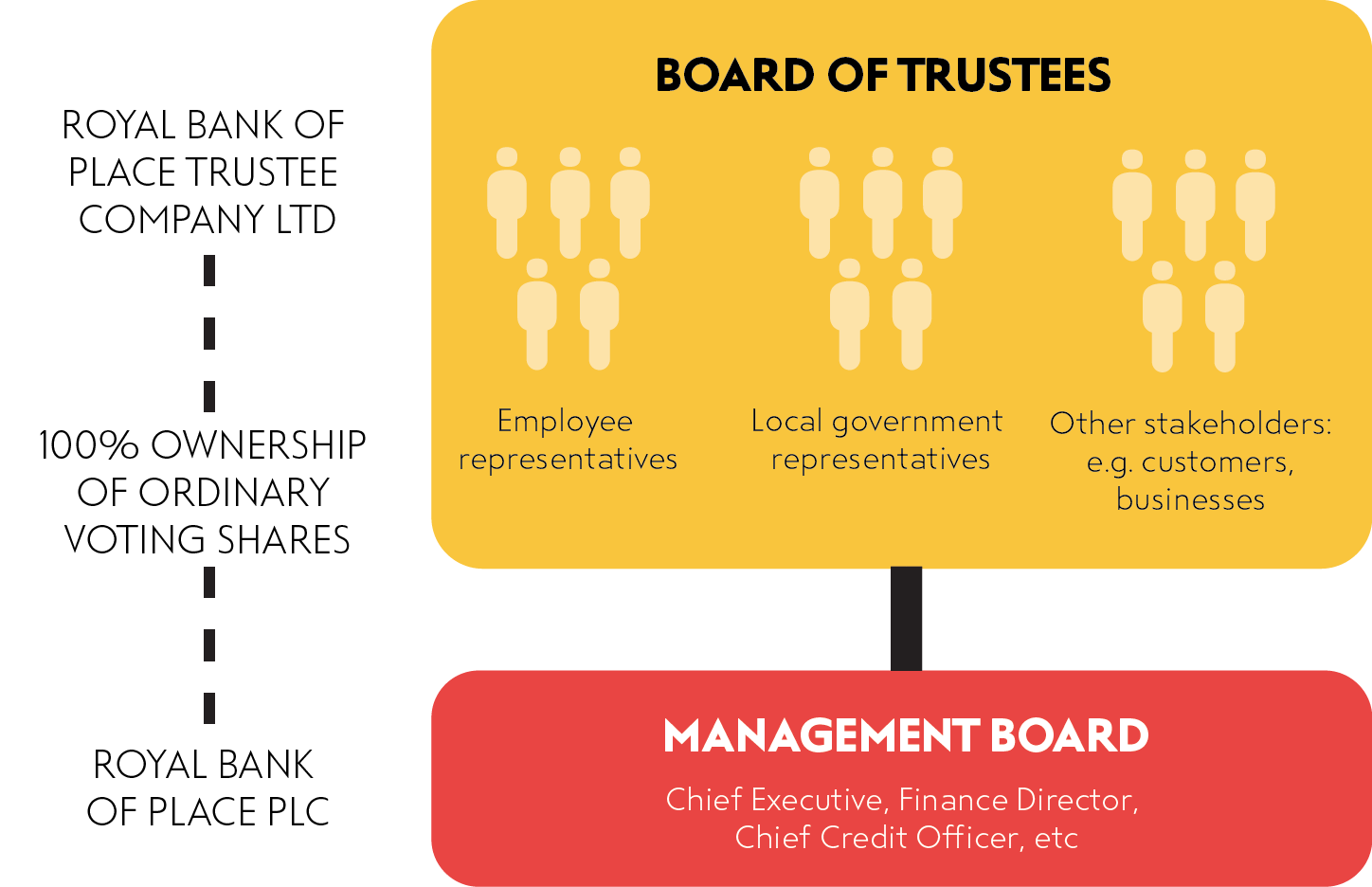

Ownership and governance

It is proposed that the new network of local banks are owned and governed under a public trust structure, which is similar to the ownership and governance model of retail group the John Lewis Partnership. Under this model, a Management Board would have responsibility for the day-to-day running of the bank, while a Board of Trustees consisting of wider stakeholder representatives would set the overall strategy for the bank and hold the Management Board to account for delivering against the bank’s objectives.

We suggest that three groups of stakeholders should be represented on the Board of Trustees:

- Local government – One-third of the Trustees should be nominated by elected representatives to provide broad representation of the citizens of the local area. It would not be the ruling party that controls the nominations, instead the right to nominate representatives would be given to all political groups, including those sitting as independents, in proportion to the votes cast at the most recent local election. This formulation prevents domination by a single party. The restriction of political representation to one-third of the Board of Trustees prevents the likelihood of interference in the banks decisions about individual lending projects, over which the Board of Trustees in any case has no jurisdiction.

- Employees – One-third of the Trustees should be elected by the bank’s employees. Worker representation on the supervisory board not only ensures that a vital stakeholder voice is heard, it can also serve as a source of on-the-ground intelligence for the Board as a whole, shortening the long lines of communication that exist in command and control hierarchies.

- Other local stakeholders – The final third of the Trustees would comprise of representatives from other key stakeholders, such as personal customers, local chambers of commerce, and representatives of other organisations, such as social enterprises and charities and educational institutions, who would provide both insight and oversight for the delivery of the bank’s public interest mandate.

Figure 5: Ownership and governance structure of new local banks

Investing in communities that have been left behind

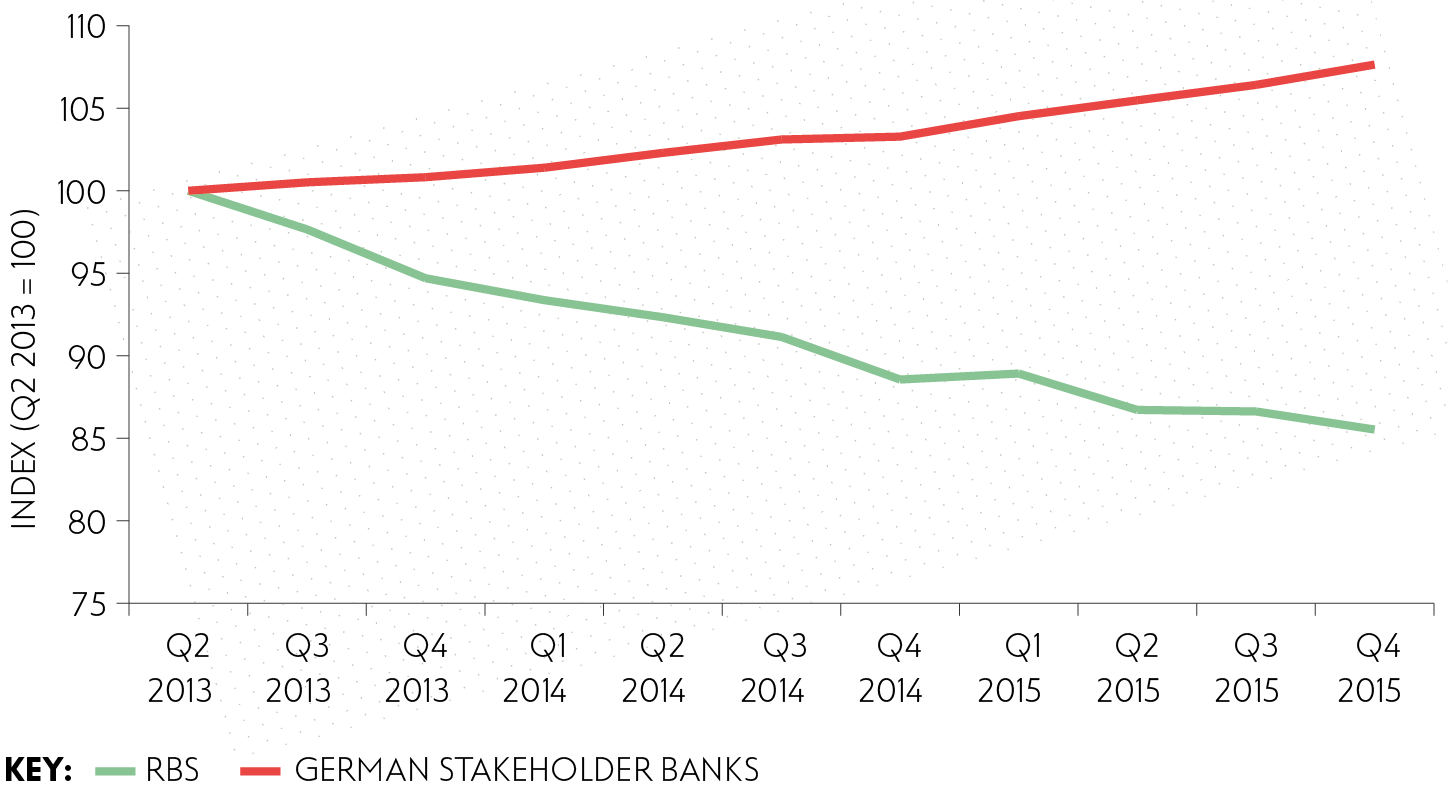

Evidence from other countries such as Germany shows that local stakeholder banking networks focus more on real economy lending. Across Europe, stakeholder banks on average lend 66% of their assets to individuals and businesses in the real economy, compared with only 37% for large shareholder-owned banks.

As figure 6 shows, German stakeholder banks have steadily increased lending to SMEs in recent years while RBS has dramatically cut back its lending.

Figure 6: SME lending – RBS and German Stakeholder banks

Source: British Bankers Association and Deutsche Bundesbank

Local stakeholder banks can maintain intimate knowledge of local people and the local economy, and evidence suggests that they are better than commercial banks at seeking and assimilating the ‘soft’ information needed to holistically assess the prospects of small firms. Often described as ‘relationship banking’, this approach ameliorates the information asymmetry which makes SME lending unattractive to larger banks, where the drive for process efficiency and control leads to centralised systems of credit scoring that become blind to regional, local and firm specific conditions.

By only investing in their local area, stakeholder banks create and retain wealth regionally rather than reinforcing existing geographic lending imbalances. This contributes to increased access to finance in areas which are poorly served by commercial banks – particularly relevant to the current UK context as commercial banks are rapidly withdrawing from rural areas.

“One of the key parts of the public service mandate of the new local RBS banks would be to act in the best interests of the local businesses, and to have a strong commitment to the local economy.”

In addition, the different customer focus of local stakeholder banking networks would entail a reweighting of RBS’s capital away from supporting credit to financial services and commercial property sectors, where London dominates, and towards lending for investment in production sectors such as manufacturing, retailing and distribution, telecoms, construction, and energy, which are more distributed throughout the regions of the UK.

Turning it into a network of local banks could therefore help boost real economy lending while investing in communities that have been left behind by our London-centric economic model – exactly the kinds of communities who voted to leave the European Union.

Jobs, skills and economic renewal

Because branches are crucial when it comes to maintaining close face-to-face relationships with customers, local banks also generally provide more extensive branch networks than larger banks. The public service mandate we propose for RBS will give it the corporate mission and financial structure that will enable it to fulfil the public interest in maintaining universal branch coverage throughout the UK.

As well as having more branches, evidence from European countries shows that local banks tend to hire proportionately more staff than large banks, reflecting the fact that this kind of ‘relationship banking’ is more labour intensive. It is also important to consider the quality of jobs, not just their quantity.

When decision-making is devolved to the local level rather than centralised to head offices, employees have more autonomy, responsibility, and opportunities to develop new skills. Each of the 130 banks will require senior management and a range of skilled professional staff from human resources to lawyers and accountants. Local banking should thus also be viewed as an opportunity to help provide good job opportunities outside of London.

5. People-powered banking that puts communities first

Eight years on from the financial crisis, it is clear that RBS is not delivering for customers or its owner – the UK public.

With the share price of RBS crashing following the UK’s vote to leave the EU, it’s time for the government to put all options for the bank’s future back on the table and urgently examine whether there are alternatives that could deliver better value for taxpayers and the economy.

Big, deep challenges require big, deep solutions. It’s time for small businesses, bank customers, rural communities and unions to unite and demand a response from government that matches the scale of the crisis we face.

By creating a network of local banks investing in disenfranchised communities, we can start transforming our broken banking system into one that works for the people.