Our railways have failed — what next?

Rail commuters in Britain faced daily misery long before this week's strike action – a combination of poor services, spiralling ticket costs and overcrowding.

10 January 2017

Rail commuters in Britain faced daily misery long before this week’s strike action – a combination of poor services, spiralling ticket costs and overcrowding.

It’s little wonder privatisation of the railways remains a recurring and contentious feature in UK politics.

Between 1994 and 1997 the publicly owned British Rail was broken up and privatised amid promises of a better, cheaper service for passengers and reduced taxpayer subsidies. The idea was that private rail companies would bring in capital and business expertise which would transform the sector’s performance.

Supporters of rail privatisation insist the break-up resulted in new investment and a better deal for taxpayers. But since privatisation the average price of a train journey has increased by 24% after adjusting for inflation – far outpacing sluggish growth in wages.

It’s the result of a highly fragmented system and the need to reward private shareholders with dividends, even as taxpayers prop up the market with generous grants. Calls for a return to public ownership are louder now than they have been for twenty years.

The system clearly isn’t working, for passengers or staff. How did we get here, and how do we build a public transport infrastructure that meets the needs of our 21st century economy?

The structure of the UK rail sector

The 1993 Railways Act replaced British Rail with a disintegrated, tripartite structure. The national rail network and its assets – such as track, bridges and signalling – were initially owned and operated by a newly created private company called Railtrack.

But after serious management shortcomings led to financial difficulties and the disastrous 2000 Hatfield train crash, the company was wound up and ownership of the rail network transferred to a new a quasi-public corporation called Network Rail.

In 2014 Network Rail was reclassified as a fully public sector entity by the Office for National Statistics, meaning that the UK’s physical rail network and assets are under currently public ownership – for the time being at least.

The debate around bringing the railways back into public ownership therefore revolves around the private train operating companies (sometimes referred to as ‘TOCs’). These companies – such as Southern Railways and Virgin East Coast – bid for a time-limited franchise to operate train services on the tracks owned by Network rail. The train operators do not own and maintain rolling stock (the industry term for the train engines and carriages), but instead lease it from dedicated rolling stock operating companies.

Heads they win, tails we lose

At the point of privatisation there was not enough revenue in the rail system to meet operating costs, capital investment and the claims of shareholders. Like most countries, Britain’s rail system was and still is loss-making. To make up the revenue shortfall, the government introduced a system of public subsidies.

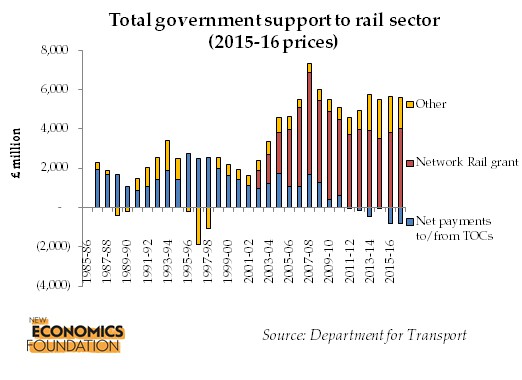

Initially this took the form of direct payments between government and train operators as part of their franchise agreement. In general, regional operators received a government subsidy, while those in the long distance and London and South East sectors paid a premium back to government. In recent years, however, successive governments have gradually reduced the amount of direct subsidies to the train operators, and since 2010-11 the premiums received have exceeded the public subsidy paid. This has led some commentators to declare that privatisation has successfully weaned the rail network off taxpayer subsidies.

“Far from producing a better deal for the taxpayer, privatisation has seen the amount of taxpayer support more than double”

However, this overlooks the dramatic shift that has taken place in the form government support to the rail sector over the past fifteen years. While direct subsidies to train operators have been falling, government grants paid to Network Rail (referred to as the Network Grant) have increased dramatically. This money is used to maintain, renew and improve the network.

Far from producing a better deal for the taxpayer, privatisation has seen the amount of taxpayer support more than double – from £2 billion in 1990 – 91 to nearly £5 billion in 2015 – 16.

Importantly, although the Network Grant (shown in red in the chart above) is initially paid to Network Rail, it is ultimately passed on to the private train operators in the form of an indirect subsidy. As part of the franchise agreement, train operators are required to pay Network Rail a fee to access the rail network. These charges have consistently been kept below the level required to cover Network Rail’s costs, and so a larger Network Grant has been needed to plug the shortfall resulting from these artificially low rail access charges.

“Without their generous public subsidy, train operators would not be generating profit.”

In economic terms, this is equivalent to a subsidy for the train operators, albeit an indirect one. As the Office of Rail Regulation states:

“The network grant is paid directly by government to Network Rail in lieu of fixed access charges that would otherwise have to be recouped from infrastructure users (i.e. TOCs). In the absence of the network grant, Network Rail would have to charge TOCs much higher access charges and, in turn, the level of TOC subsidy would also need to be much higher. As such, it is important to bear in mind, when considering the fall in direct subsidy paid to TOCs, that it does not capture the implicit government subsidy they receive via the network grant’s effects on access charges.”

In 2013 – 14, train operators paid out nearly £200 million in dividends to private shareholders. These profits had little to do with investment and innovation. Instead, train operator profits are sustained thanks to a complex subsidy system which obfuscates the economic reality and creates an illusion of financial self-sufficiency. Without their generous public subsidy, train operators would not be generating profit.

Train operators are actually engaging in a form of ‘rent-seeking’ – profiting not by creating new wealth or adding any real value, but by exploiting a position of monopoly privilege to extract existing wealth from others.

They don’t provide new capital investment, because rail infrastructure is provided by the publicly owned Network Rail. They don’t maintain the stock of existing assets, because the rolling stock is rented from a leasing company. They don’t have to worry about losing customers, because customers can’t switch to another provider if the service is poor. They are also sheltered from downside risk in a way that normal companies aren’t: they can walk away from the arrangement if things go wrong, leaving the state to deal with the mess.

We, as passengers and taxpayers, are the ones who lose out.

Taking control of the railways

Rail passengers have been failed by privatisation. It’s clear we need a new system that puts their interests over private shareholders.

“The government doesn’t have a problem with publicly owned companies running the railways — so long as they are not owned by the UK public”

Ironically, many of the UK’s train operators are already “publicly owned” — albeit as subsidiaries of other European states’ national rail companies such as the German national rail company Deutsche Bahn, the French national rail operator SNCF and the Dutch state operator Nederlandse Spoorwegen.

The profits made by these companies – which are sustained only because of British taxpayer subsidies – are then used to improve public rail services in Germany, France and the Netherlands. Clearly the UK government doesn’t have a problem with publicly owned companies running the railways – so long as they are not owned by the UK public.

The success of the European railways demonstrates that public ownership could deliver better results for customers and taxpayers in the UK. And there are other examples from closer to home too.

In 2009 the East Coast line was taken into public ownership after National Express walked out on the contract. The service had a 91% customer satisfaction rate, required much less public subsidy, paid back £1 billion to the Treasury and was the most efficient franchise in the UK.

A modern and efficient public rail service is entirely possible – and affordable. Importantly, taking control of our railways would not cost a penny, as each line could be brought into public ownership when the franchise with the train company ends.

Doing so would cut fares, removing dividends and other administrative costs associated with rail franchising from the system. Recent research by the TUC found that these savings over the next five years would be enough to fund a 10 per cent cut on regulated fares.

Public support for taking control of the railways is strong – according to a recent YouGov poll just 21% of the public are opposed to the idea.

It’s time to build a railway system that puts passengers – not shareholders – first.

Topics Transport