Credit where it’s due

Ten years after the Lehman collapse, finance still hasn't been fixed

14 September 2018

Ten years after the failure of Lehman Brothers brought the global financial system to the brink of collapse we still have not addressed the fundamental problem: the nature of how finance operates.

As with all financial crises, the 2008 global financial crisis one was caused by the failure to adequately constrain the banking sector’s ability to create and allocate credit.

Ten years on, the banking sector is still failing to supply the right types of credit to the right parts of the UK economy. The allocation of bank credit is still fundamentally misaligned with key social and economic objectives, and will not help us tackle some of our biggest and most pressing challenges – like climate change, the housing crisis, inequality, and the productivity puzzle.

A well-designed financial system is not a silver bullet to fix all our economy’s flaws, but it is one of the single most important things to get right. In the absence of reform, finance risks ‘locking-in’ and exacerbating large swathes of the UK’s prevailing weaknesses.

This why we need a proactive credit policy framework that helps realign credit allocation with democratically defined social goals.

Ten years on

The 2008 global financial crisis showed us that left to their own devices banks deliver sub-optimal levels of credit, helping to swing the economy from boom to bust. Since 2008, a number of positive regulatory reforms have reduced the risk of another bailout (including ringfencing and the introduction of a macroprudential regulatory framework).

But the fundamental truth is we haven’t done enough to reform the underlying nature of banking – and its tendency to inappropriately allocate credit.

UK growth rate of financialisation

The UK continues to experience unprecedented growth in the scale, size and power of the UK financial sector, known as ‘financialisation’. But despite the surge in financialisation, banks are failing to support the industrial and sustainable activities that would boost the productive capacity of the economy and facilitate the green transition required by today’s environmental imperative.

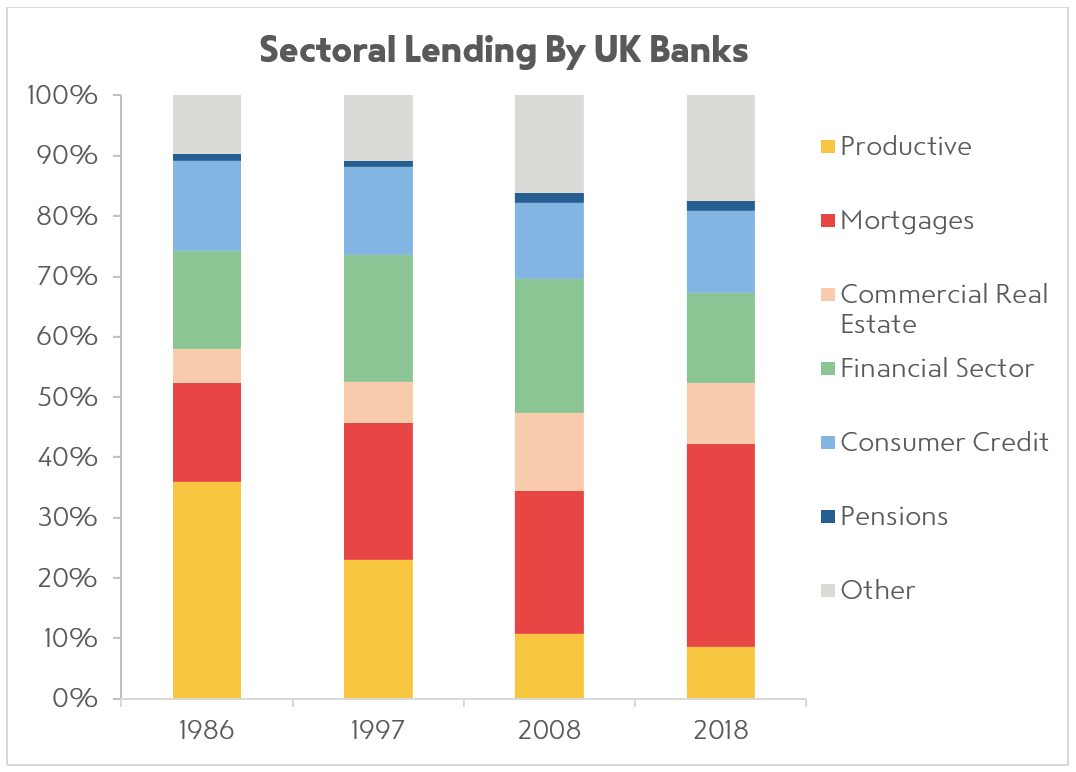

The majority of bank lending is still for non-productive and speculative undertakings, in particular real estate and financial trading, as well as ecologically damaging activities.

With not enough credit financing investment for the productive sectors of our economy, living standards are falling and green transition remains illusory.

Source: Bank of England

Misaligned credit is also a driver of wealth inequality, as the majority of bank lending leads to asset price inflation, increasing the wealth of asset holders, and the proceeds of owning wealth are outstripping investment in the real economy.

Conventional policy frameworks are not well equipped to deal with these challenges, as they still assume that credit markets will naturally self-correct towards equilibrium – that banks still allocate an optimal level of credit to the economy when the central bank is able to find the natural rate of interest.

Credit guidance: the way forward

In this regard, some ideas are already beginning to flourish. IPPR has suggested that the Bank of England influence credit conditions to freeze house price growth, while the Labour Party’s Turner review similarly suggested the Bank follow a productivity target.

Whether you agree with these specific objectives or not, this thinking is at least a step in the right direction. The logical next step to bring the debate forwards is to start thinking about specific instruments that can give policy makers more influence over the allocation of credit.

Credit guidance amounts to a form of interventionist credit policy, deployed on behalf of central banks with potential support from the Treasury, as means of directly influencing the allocation of credit flows for particular sectors.

Macroprudential policy is perhaps a step in the right direction, but this only really focusses on mitigating financial instability, neglecting the need for patient capital, productive credit, and real capital formation (or real income generating activities).

Other forms of credit guidance interventions could include introducing; a minimal ratio of lending to the real economy (non-real estate), credit ceilings, credit quotas, interest rate ceilings, rediscounting ceilings, targeted refinancing lines, and the establishment of public intermediaries with the express purpose of lending to particular sectors.

Credit guidance policies were the historic norm not the exception. Policies aimed at influencing the level of credit available to particular sectors played a prominent role in most Western countries post-war reconstruction and growth processes, and were pivotal to Europe’s Golden Age.

In a similar vein, these policies were imperative to the rapid expansion in post-war Japan, the recent growth of China, the development of East Asian miracles, and the growth of ‘other’ emerging economies.

As noted by Richard Partington of the Guardian, “The gleaming towers of Canary Wharf or the City might be potent symbols of free-market capitalism, but they are state sponsored. The financial system is a perversely socialist endeavour. It is the ultimate welfare recipient.”

The banking sector is potentially the most subsidised industry in the UK. With banks benefitting from a number of guarantees from the government and implicit subsidies, policy makers would be justified in implementing interventions that ensure bank credit allocation activities are more aligned with democratically defined objectives

A fair criticism, however, is that the liberalisation of international capital flows and the free movement of capital in the 1970s and 1980s may have rendered credit guidance policies increasingly ineffective. In more open, financially deep and liberalised economies, banks could circumvent credit guidance policies.

In this respect, demand side (borrower-based instruments) have proven most successful in curbing credit growth for particular sectors in advanced economies. Similarly, incentive based schemes (like lower discount rates or a tweaked Term Funding Scheme that specifically offers lower interest rates for banks lending to business) may prove more successful at boosting bank lending to the productive sectors of the economy.

Ultimately, given the prominent role central banks play in lending to the banking system – and the dependence the former has on the latter – public authorities have the ability to significantly affect the volume and direction of credit flows if they wish to.

It’s more of question of whether they want to, not whether they can.

Join the #ChangeFinance rally in the City of London on 15 September 2018.

Topics Banking & finance