Why inequality is an economic problem

18 December 2014

Rising economic inequality was a major driver of the financial crisis. With the OECD recently debunking ‘trickle-down’ economics, our new report sets out the links between inequality, the growth in scale and influence of the financial sector, and the dangers for financial stability.

A fragile recovery

A return to growth in economies such as the UK and USA has been welcomed as a sign of recovery from the 2008 financial crisis. But as GDP picks up, so too has the widening gap between rich and poor.

The crisis may be over for the wealthy but the aftermath for ordinary workers – depressed wages and growing debt – is only getting worse.

Most nations have mustered only negligible growth – and this has failed to benefit the vast majority of those nations’ populations.

In the seven years following the crash, the UK has suffered the longest sustained decline in real wages since records began.

This decline hasn’t been shared equally across the income spectrum – latest annual data up to the end of 2013 shows real earnings for the top 10% increasing by 3.9%, and a 2.4% fall for the remaining 90%.

Households are once again piling on risky personal debt at a rate of almost £1 billion a year.

Globally, wealth grew by 8.3% last year to $263 trillion, even as living standards stagnate for the majority. Income inequality has seen a sharp return – the top 1% of earners have reaped 95% of the USA’s economic gains since the crash.

Inequality increases as economies are financialised

Over the past four decades, financial sectors have been extensively deregulated and have expanded enormously as a result, particularly in the UK and USA.

This deregulation produced two systemic outcomes: finance has been freed to become the motor of the economy while the pursuit of greater equality of citizens, as was the focus after the second world war, has been abandoned.

Instead, the notion that an unrestrained pursuit of wealth would trickle-down from rich to poor has been embraced in the mainstream political and economic arenas.

Financial markets, products, and firms now play a much larger role in many areas; from pensions and social insurance to homes and public infrastructure.

Privatisation and the doctrine of maximising value for shareholders have increased the amount of economic activity focused on extracting the largest possible short-term profit. These trends are referred to collectively as ‘financialisation’.

Until now the connections between this increasing prevalence of financial activities and the steady increase in economic inequality have not been clear. But when these two trends reached boiling point in the mid-2000s they fuelled a global collapse of financial systems.

The polarisation of wealth and incomes fed asset bubbles, risky financial activity and necessitated vast levels of household debt – resulting in the 2008 financial crash. With little done since to address these interconnected drivers, the threat of another crisis is very real.

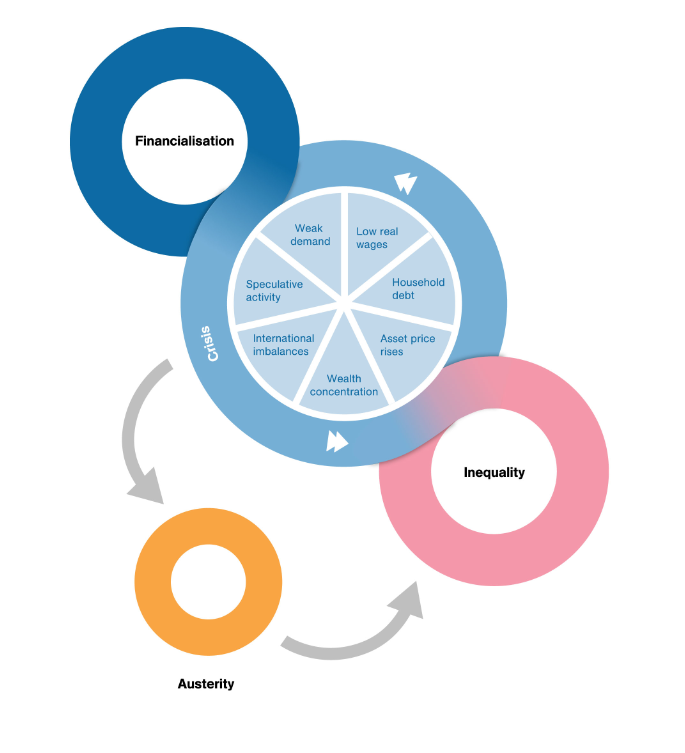

This diagram lays out the seven indicators of economic instability, each fuelled by rising inequality and increasing financial sector activity:

Our report describes how these indicators laid the path for the 2008 crash, and threaten to do the same again:

- Increasing inequality depresses demand since consumption levels depend more on the wages of those at the lower end of the income scale, than the profits of the wealthy

- In the face of stagnating wages, households rely increasingly on debt to maintain their lifestyles with rising asset prices, especially in residential housing, worsening this.

- Financial liberalisation allows money to flood into countries with trade deficits, such as the USA and the UK, providing the funds for debt-led consumption.

- Snowballing wealth at the top increases risky financial speculation.

Inequality doesn’t bring growth, it brings economic instability

In recent years there has been a marked slowing of growth across the world’s wealthiest economies, with none returning to the growth trends experienced before the crisis. Many have begun to speculate that this stagnation could, in fact, be a permanent development – meaning that wealthy economies are fundamentally unable to create enough demand to keep growing.

The mainstream political consensus has for decades now suggested that inequality is a price worth paying for economic growth.

But new research from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) shows definitively that this inequality/growth trade-off is false – adding to a growing body of research showing that inequality actually prevents economies from growing. This points to a fundamental structural flaw in the economy: if the proceeds of growth are not shared, the pie stops growing.

The pursuit of higher returns for the already wealthy within this dwindling pie cannot persist forever. With wealth refusing year on year to trickle down, debt has been used to plug the wage-consumption gap for the rest.

The signals are showing quite plainly that this pursuit of growth, via inequality, is ineffective and unsustainable.