3 things we’ve learned about the future of the UK economy

Today's OBR assessment shows big change is on the way

23 November 2016

The first post-Brexit budget, and the OBR projections published today, confirm two things: firstly that Brexit does indeed have grave implications for the UK’s economy; secondly, that neither Brexit nor the current government show any signs of genuinely shaping the UK economy towards a better, more inclusive growth model.

Here are three examples of the impact of Brexit, as assessed by the OBR:

1. The implications of Sterling depreciation

Commentators and analysts have repeatedly claimed that the one silver lining to Brexit will be the effect of the devalued pound on our exporters. The story goes that with our exports much cheaper than they used to be there could be a renaissance of production, especially manufacturing, across the country.

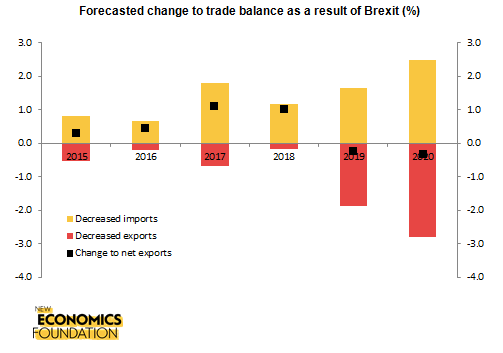

But forecasts published by the OBR today should put this dream to rest. Comparing their forecasts from March this year with today’s equivalent shows that Brexit is expected to reduce exports in every year until 2020 compared to pre-referendum expectations.I

It is expected to improve our trade balance between now and 2018, but this is only because our imports are expected to fall even more than exports. This collapse in imports reflects the expectation that consumers will get poorer, so it’s no real reason to celebrate. By 2019 the overall effect on the trade balance is negative as the UK becomes a “less trade-intensive economy”. This is a picture of decay, not resurgence.

Undoing our large trade deficit is going to require more than wishful thinking about a devalued pound. One can’t expect an economy posting a trade deficit and manufacturing decline for almost 20 consecutive years to shift towards an export-based model overnight, just because exchange rates have changed. It will require more domestic supply chains, new skills, financial capital willing to invest in risky endeavours, and improved infrastructure, and these all take time to build.

But we need to take the first step – today’s Autumn Statement went nowhere near far enough towards a genuine rebalancing of the economy. Meanwhile, imported inflation will erode the purchasing power of ordinary people, in effect jeopardising incomes – and poorest will suffer the most.

2. The implications of reduced private investment

The first post-referendum budget forecast also confirmed that we should expect lower business investment as a consequence of Brexit.

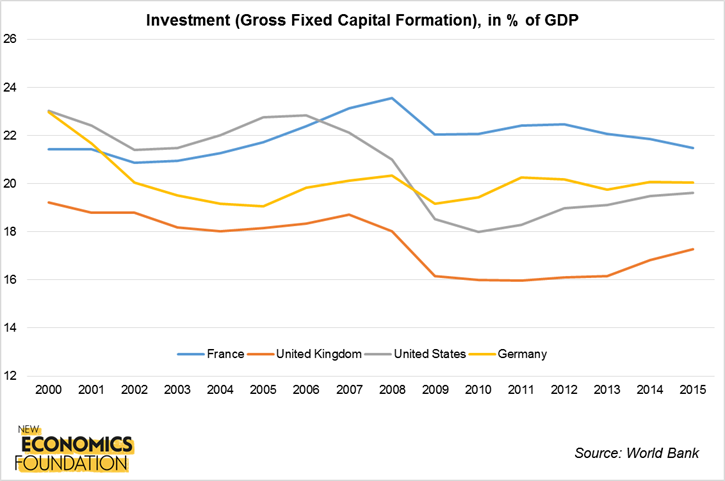

This is bad news for the economy: low investment compared to other countries has been one of the key drivers of flat productivity growth since the onset of the crisis, which in turn is one of the factors behind real wages decline since 2008. Less investment is also likely to lead to fewer good jobs around the country.

But there is a wider point too: unless investment in the real economy increases substantially, particularly in regions left behind, a genuine rebalancing away from the City and finance will remain an empty promise.

3. The government is still not doing enough

The Chancellor suggested that his newly announced ‘National Productivity Investment Fund’ would help mitigate these economic “headwinds” and enable other regions of the UK to ‘catch up’ with London’s high levels of productivity. But this is also fantasy. Over-reliance on high profits in the City is a core part of our economic malaise. Addressing it requires deep structural changes to our economy – not what the OBR described as a “modest giveaway” of public investment.

Although the £23 billion of infrastructure investment promised by the Chancellor is a step in the right direction, it actually represents a relatively small net increase (one analyst has calculated it at just £4.6bn). This is clearly insufficient to deal with low productivity growth and address the needs of people around the country.

The Chancellor equally failed to explain where this money is going to be invested. The problems of the UK economy are indeed geographically localised. Brexit will disproportionately hit the regions which are already left behind – and this means that additional public investment should specifically target those regions.

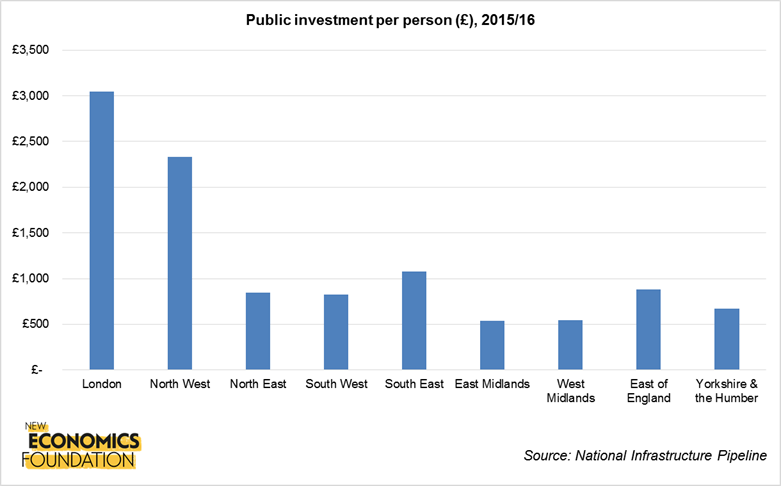

If judging from current breakdowns (see figure below), where the average Londoner receives three times more funds for public investment compared to the average North Easterner – then there is a risk of failing to channel additional funds to places which need it the most.

What we needed from today’s Autumn Statement was a bold new industrial strategy to give real control to struggling communities up and down the country. We needed a willingness to genuinely rebalance the economy by transforming our financial system into one focused on supporting communities rather than on speculation. Instead, these communities have been offered token amounts of public money and expected to mimic the City’s economic success.

Big change is certainly coming for the UK economy, but at the moment, it’s not at all clear that it’s going to be for the better.

Topics Macroeconomics