5 things Philip Hammond forgot to mention in his Budget

The Chancellor dodged Britain's biggest issues

09 March 2017

Yesterday Philip Hammond delivered his first Budget as the new Chancellor of the Exchequer. The Budget comes at a critical time for the UK. We face some of the biggest economic challenges in decades, but listening to Mr Hammond’s speech it would be easy to think otherwise.

The Chancellor painted a rosy picture of a robust UK economy enjoying strong economic growth and low unemployment. He also talked about how the government is helping ordinary working families and building an economy that works for everyone.

That’s far from the reality facing most people this morning. Here are five things he forgot to mention:

1. We face an unprecedented lost decade in living standards

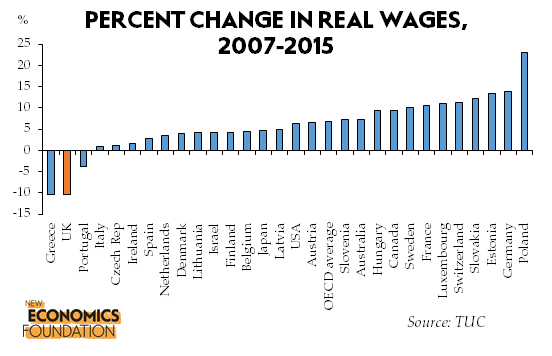

Since 2007 real wages – income from work adjusted for inflation – have fallen by 10%. Wages in Britain have fallen further than in any other advanced country apart from Greece. This represents the longest sustained decline in British living standards since records began.

According to the Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) forecasts which were published alongside the budget, we face another year of wage stagnation in 2017. The OBR expects that the weaker pound caused by Brexit will push up inflation, eroding the purchasing power of any wage increases.

While the OBR does expect moderate earnings growth beyond 2017, this will not be sufficient to make up the loss ground. In fact, the OBR expects that in 2020 real earnings will still be lower than they were back in 2008. The implications of this are stark: we are facing an unprecedented lost decade in living standards.

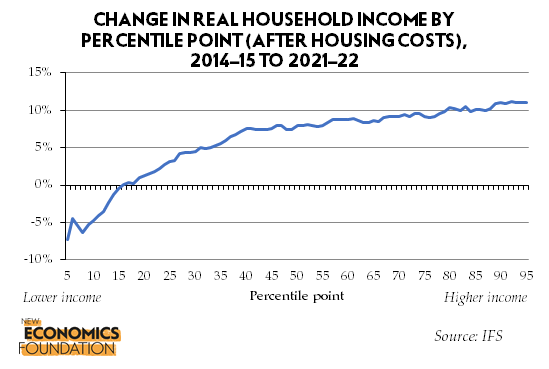

But these aggregate figures mask varying fortunes across the income distribution. The problem of low wage growth is further compounded by the government’s cuts to working-age benefits which will hurt the incomes of those at the bottom of the income distribution.

In a report published last week, the Institute for Fiscal Studies projected that while most households can expect moderate income growth over the next five years, the incomes of the poorest 15% of households will fall (after adjusting for housing costs and inflation). As a result, income inequality looks set to increase.

2. Private debt is ballooning, putting our economy at huge risk

Mr Hammond said that yesterday’s Budget was about continuing the task of “getting Britain back to living within its means”. He also said he will “not saddle our children with ever-increasing debts”.

He was of course referring to reducing government spending. Yet when we look at the consequences of the Chancellor’s Budget on private households, the government’s own figures show no signs of progress towards any conception of a society that is living within its means.

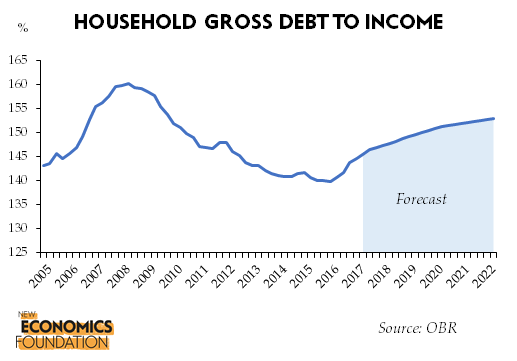

The below graph is taken from the OBR’s latest set of forecasts which were published alongside the Budget. It shows what has happened to household debt relative to income over the last decade or so, and what they expect to happen over the next five years:

So, the government’s own forecasters think household debt relative to income will increase dramatically in the next five years.

What’s going on here? Firstly, the OBR is forecasting that mortgage debt will continue to rise as house prices grow more quickly than incomes. With UK house prices already nine times average incomes – a consequence of financial deregulation and ill-thought out housing policy – this is a worrying sign.

Secondly, in recent years the UK economy has become increasingly reliant on household consumption spending. With wages failing to keep up, households have only been able to increase consumption by borrowing more or drawing down on savings. And with a government determined to curb spending, a trade deficit that is a drag on economic activity and sluggish business investment, the only way that growth can plausibly be achieved is through debt-fuelled consumption. This is not sustainable – eventually, an economy which relies on households spending beyond their means will crumble.

3. The NHS isn’t getting the funding it needs

In his Budget speech Mr Hammond declared that “we are the government of the NHS”. This comes amid reports of a “humanitarian crisis” in hospitals, while doctors have warned that mounting pressures on the NHS are putting lives at risk.

The Chancellor said that he is committed to making more funding available, but by simply reeling off big numbers – “an extra £10 billion” – he obscures the underlying reality.

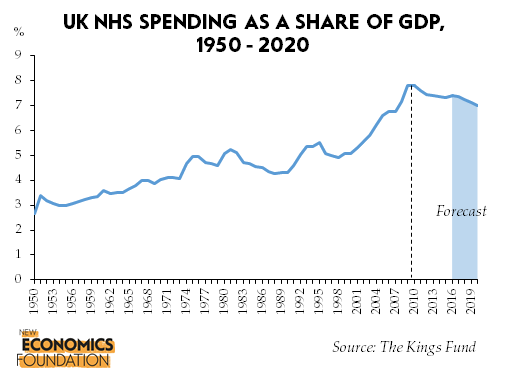

The most effective way to evaluate trends in health spending is by comparing it to the size of the economy. There are good reasons why health spending should increase relative to the size of the economy over time. An ageing population means that demands on health services rise since older individuals on average consume more, and more expensive, healthcare. Demand will also increase over time as a result of the rising prevalence of some chronic conditions, improvements in access to care, and improvements in technology.

Over recent decades spending on the NHS has indeed increased: in 1970 total UK health spending was 4% of GDP, rising to between 5% and 6% through the mid-1990s. From 1997 until the financial crisis in 2008 there was a steady increase, reaching nearly 8% in 2010.

Since 2010 however, this trend has reversed. As the Kings Fund has reported, we are now experiencing the largest sustained fall in NHS spending as a share of GDP in any period since 1951.

The extra money announced for social care in the Budget may help to alleviate pressure on the NHS by freeing up some beds. But the inescapable reality is that the NHS needs much more funding. Where this money should come from is an important question.

According to the Institute of Fiscal Studies, the corporation tax cuts since 2010 have cost the government £10.8 billion a year in tax revenue. In the Budget the Chancellor confirmed that he plans to reduce corporation tax even further to 17% by 2020. This is money that could go a long way to fixing the problems in the NHS.

At a time when the NHS is in crisis caused by lack of funding, slashing corporation tax further seems grossly irresponsible.

4. What about the housing crisis?

The Chancellor failed to mention housing even once, despite the fact that we are in the grip of a serious and escalating housing crisis. One of the things fuelling that crisis is the fact that the government is insisting on selling off public land rather than using it to help deliver more genuinely affordable housing.

At the current rate, the new homes target on sold-off public land will not be met until 2032, 12 years later than promised. And the majority of homes being built on the land sold are out of reach for most people — only one in five will be classified as ‘affordable’. Even this figure is optimistic as it uses the government’s own widely criticised definition of affordability. If the government ended the public land fire sale they could use that land to partner with local authorities, small developers and communities themselves to deliver the more affordable homes people need.

According to the latest Nationwide House Price statistics, as most people cannot afford to buy now even with a mortgage, cash buyers such as second homeowners and buy to let landlords are propping up the market. Things are getting worse for people left at the mercy of this failing market. The Chancellor could have put a stop to the fire sale of public land yesterday, but instead he acted as if there were no housing crisis all.

5. The Chancellor quietly ducked acting on the environment

With the nation’s cities gasping for clean air and ever-louder calls for politicians to act on dirty transport, the Chancellor had been widely expected to announce a new scrappage scheme for diesel cars – but he didn’t.

Pollution from traffic is the biggest factor in the 40,000 early deaths in the UK every year from dirty air, of which diesel vehicles are the biggest culprit. New research shows that a scheme to incentivise trading in dirty diesel cars for cleaner new models would be popular and successful, as well has helping support the Government’s broader industrial push to be a global hub for making low-emission cars. But the Budget documents deferred the decision on the scheme until later in the year, and Mr Hammond made no mention of the country’s air pollution crisis at all.

This Budget had little time for anything environmental. Previous promises that it would see an announcement of post-Brexit subsidy plans for renewable energy were also ducked. Yet there was the usual succour for the country’s fossil fuel producers, already basking in the “unprecedented support” of successive Budgets. This time, they will help design a tax change that will encourage smaller companies to wring every last drop of oil from the UK’s declining North Sea – despite the Government admitting most of the world’s fossil fuels will need to be left in the ground.

Today the Chancellor faces a growing backlash over National Insurance rises and whether it constitutes a breach of the Conservative’s 2015 manifesto. But yesterday’s Budget represents a wider failure.

This was a moment to take the first steps towards an economy that really puts people in control and to prepare Britain for life outside the EU. Instead, the Chancellor ducked the big issues and dodged difficult choices.

Topics Macroeconomics