Redesigning tax for a just, green recovery

The UK’s tax system promotes inequality and fails to prevent environmental degradation. Here’s how we can change it.

01 June 2020

In response to Covid-19, the Treasury is considering changes to the UK’s tax system on a scale not seen for decades. While changes to the tax system are much needed, there is a danger that reforms fixate on ‘shoring up’ public finances after Covid-19, which would be the wrong approach and neglects the key reasons for an overhaul. Rather, the tax system offers a powerful tool to shape economic activity and combat systemic issues that long predated Covid-19, such as inequality and environmental degradation. Proposals for redesigning tax should reflect this capacity. If we are to achieve a green and just recovery from Covid-19, both the purpose and the sequencing of these proposals will be vital.

While spending cuts would be more harmful still, there is also no need to increase tax revenues in the near term to support public finances, for two reasons: first, borrowing is currently a cheap and sensible alternative, and second, increasing taxation in the midst of the crisis could jeopardise the recovery. Despite a significant uptick in UK government borrowing to tackle Covid-19 and support a necessary period of economic hibernation, the cost of this borrowing remains at historic lows, meaning the debt remains entirely affordable. Indeed, even if the debt doubles (an outcome that far exceeds most forecasts), the current cost to the taxpayer to pay for it will remain lower than at any time in the 20th century.

Enacted too quickly, higher taxes on incomes, consumption or productive investment could needlessly jeopardise recovery by suppressing economic activity and prolonging a deep recession. At this stage, facing a potentially severe economic depression as well as an accelerating climate emergency, it is not only responsible but advisable to borrow to finance a Green New Deal-led recovery: investing in green infrastructure projects, upskilling a ‘green workforce’, creating jobs restoring nature and biodiversity, and increasing funding for the low-carbon forms of work proven so invaluable by this crisis, like health, social and child care. We must also begin to consider tax reform beyond the immediate crisis to support long-term prosperity, equality and sustainability.

Taxes for a Green New Deal-led recovery

The UK’s tax system currently fails to adequately combat high levels of inequality, and fails to sufficiently inhibit harmful behaviours leading to environmental degradation — two essential tasks in a just, green recovery from Covid-19.

Tax is unfairly distributed in the UK. Analysis by the Office of National Statistics finds that the overall combined effect of direct and indirect taxes is to slightly increase inequality. The tax system currently supports a vastly unequal distribution of wealth and income, contributing to increasingly untenable levels of inequality in the UK. Income inequality has increased sharply since the 1970s, while top income tax rates plummeted from 80% to 45%. Meanwhile, the richest own the vast majority of personal wealth, but wealth is taxed at a significantly lower rate than income. Recent research from the Resolution Foundation highlighted how excluding capital gains (which are taxed at a lower rate than income from work) from calculations of income inequality has contributed to a significant underestimation of income inequality in the UK.

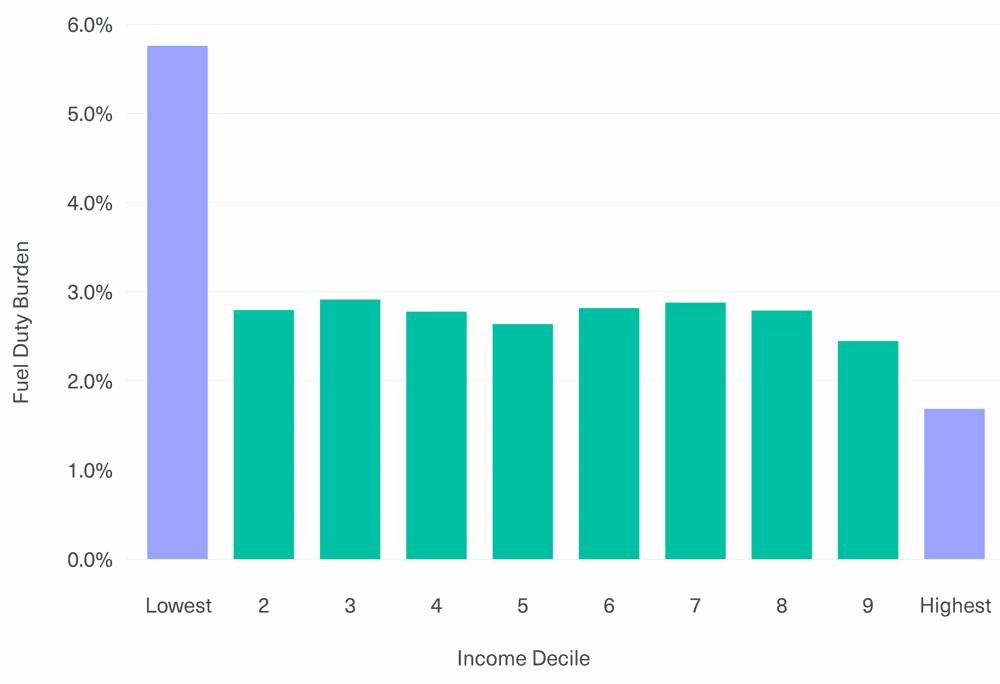

Moreover, taxes on polluting and carbon intensive forms of production and consumption, as well as tax reliefs for ‘clean’ production and consumption, fall far short of what is needed to confront the climate emergency. Over the past two decades, revenues from taxes categorised by the Office for National Statistics as ‘environmental’ have declined, as a fraction of both GDP and total tax revenues, and many of the UK’s current suite of environmental taxes exacerbate inequality, disproportionately impacting those on lower incomes. For instance, as shown in Figure 1 below, Fuel Duty – a flat tax on all motorists – places a significantly higher burden on the lowest income car owning households in the UK. Since access to alternative modes of transport is also limited in many parts of the country, some of the poorest households are forced to pay this higher burden out of necessity.

Figure 1. Fuel Duty burden by income decile, for car owners only, 2020 – 21

Source: NEF analysis using Living Costs and Food Survey Data, 2017/18

Note: We define Fuel Duty burden as proportion of equivalised household income after housing costs. We show impact by decile as a proportion of income, rather than expenditure, as considering expenditure ignores the potential need for borrowing in order to spend, which particularly impacts those in the bottom decile.

This is just one example of the potentially unjust outcomes that may result from environmental taxes that neglect the social and economic correlates of carbon consumption, nor pursue environmental goals concurrently with economic justice. A transformed UK tax system could provide vital support for a just, green recovery from the economic fallout of Covid-19, but to do that, reform must adhere to the following principles:

1. Contribute to meeting rapid decarbonisation targets

The climate emergency continues to deepen precisely because governments have to date consistently fallen short, both on the necessary scale of investment and on measures such as tax and subsidy that shape the nature of carbon-intensive or environmentally destructive production and consumption. Contributing to the effective, rapid reduction of carbon emissions is an essential task for a reformed system of taxation as part of a Green New Deal-led economic recovery. Reform must seek to penalise carbon-intensive activities – both production and consumption – while using effective reliefs and subsidies to encourage activities that support the transition to a decarbonised economy.

2. Support a green recovery rooted in the redistribution of wealth and power

There is good evidence that emissions rise with income, with poorer households contributing proportionately fewer emissions than richer households. However, in the UK certain polluting activities like international aviation – which is disproportionately undertaken by a small minority of the population – are undertaxed, while high rates of tax are applied to more widely distributed activities, such as private vehicle use and general consumption through VAT.

Further, while those on lower incomes may produce fewer emissions, they may also be locked into such emissions by structural economic factors, for instance because they are less able to work from home or need to travel further for work, cannot afford to purchase a low-carbon vehicle, or live in an area where no viable or affordable low-carbon alternative to car use exists. A just tax system should address these structural differences – even if every individual tax cannot be perfectly progressive, the system as whole must more than correct for this on aggregate.

3. Commit to global solidarity

Just as the UK’s carbon emissions contribute to climate change globally, the influence of the UK tax system also reaches far beyond our borders. Through its complex web of tax havens, the UK is a principal enabler of tax evasion and avoidance, thus undercutting the tax sovereignty needed for rapid decarbonisation and climate justice to become a reality in other states.

To address these issues, the UK should: increase its main rate of corporation tax to a level that ensures it does not promote a race to the bottom; pursue international best practice for clamping down on tax avoidance and evasion; take decisive action to shut tax havens under its jurisdiction; and support international measures to make polluters pay.

Harnessing tax for climate and economic justice

Covid-19 has reinvigorated a debate over the role and design of the tax system, but this debate must centre on harnessing tax as a tool to support a more just, equal and sustainable economy, rather than a narrow fixation on the public finances. Over the coming months, Common Wealth and the New Economics Foundation will explore the design of a tax system needed for a Green New Deal-led recovery and beyond. Our work will evaluate some of the key taxes currently in place throughout the UK that impact the climate and the natural environment, in addition to inequality, and outline the strengths and weaknesses of these taxes as tools for achieving our core goals. This evaluation will inform proposals for new or redesigned taxes that can support climate and economic justice.

Image: Unsplash

Campaigns Share the wealth