Public debt and debt servicing costs: The nightmare that never was

Debt servicing costs needn’t keep the chancellor up at night, maybe environmental breakdown should?

19 November 2021

Not too long ago, the state of public finances was thought to be giving chancellor Rishi Sunak “sleepless nights”, as he struggled with Britain’s growing debt levels and how to pay it all back. But then it became clear that the Bank of England was bankrolling the Coronavirus bill and in almost a blink of an eye, it was as if the last ten years of devastating public spending cuts may have been for naught, what we were told about public finances might have been flawed, or worse, politically doctored to justify a narrow ideology.

As the penny dropped, the majority of public commentary began to show a greater appreciation for the fact that debt and deficit (the negative difference between government revenue and spending) levels are less important than the actual cost of servicing debt (i.e. the interest we pay on that debt). Net interest payments had fallen fourfold, from 3.8% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 1980 – 81 to 0.9% in 2020 – 21, despite the debt-to-GDP ratio more than doubling from 40% to 97% over the same period.

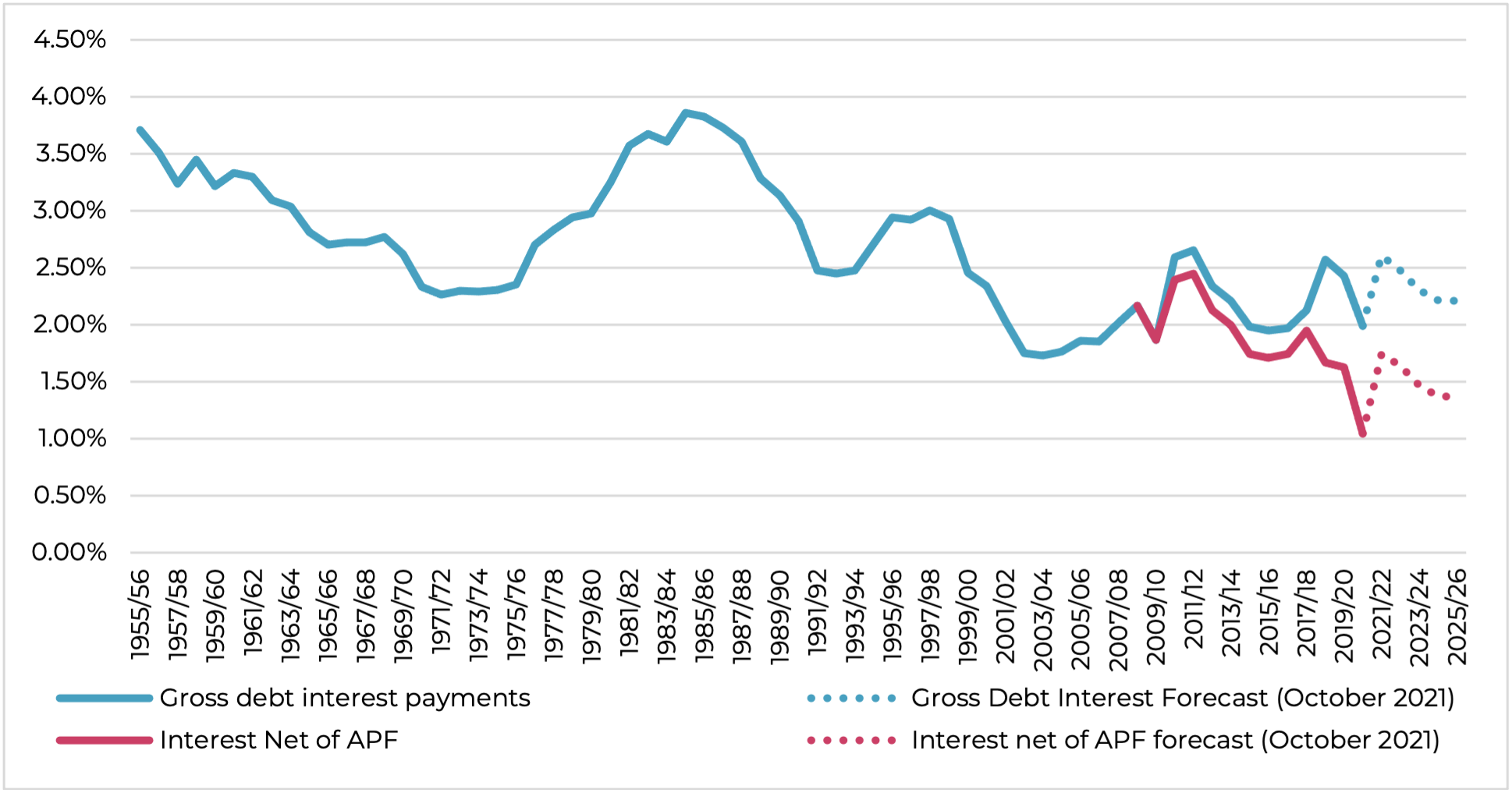

Government debt-servicing costs at historical lows

Government interest payments: gross and net of asset purchase facility (APF) as proportion of GDP, 1955 – 2026

Source: OBR 2021 & author’s own calculations

But many still argue that, despite borrowing costs having reached historical lows, the situation is still very fragile, as a potential increase in inflation, and the associated increase in interest rates by the Bank of England (BoE), will raise government debt servicing costs. This is why the government is targeting declining borrowing levels. For example, borrowing over the next five years is forecasted to be 6% lower than estimated in March 2021. As a result, the government will only be deploying £25.5 billion of net zero spending between 2021 – 22 and 2024 – 25, when it should be spending at least £30 billion a year.

In part, the government’s debt servicing costs could increase because certain government borrowing instruments (index-linked gilts) pay an interest rate that is tied to inflation (as inflation increases, so do government debt payments). Meanwhile, the government’s public finances are more sensitive to an increase in interest rates because the BoE pays interest (the BoE’s policy rate) on the central bank reserves it creates — i.e. it currently pays 0.1% on the £895 billion of money created through its quantitative easing programme. If it raises interest rates to help control inflation, say to 0.25%, it will have to pay out more in interest to the banks that hold the central bank’s reserves.

All this means is that government interest servicing costs are much more sensitive to a change in interest rates and inflation. Earlier this year, in the chancellor’s autumn budget speech, it was suggested that a 1% increase in inflation and interest rates would increase the cost of servicing debt by £23 billion. Factoring in higher projected future inflation and interest rates, the Office for Budget Responsibility is now forecasting that debt servicing costs will rise to a total of £40 billion in 2022 and 2023.

While these figures should not be taken lightly, there are a number of reasons why we should not rush to the panic button.

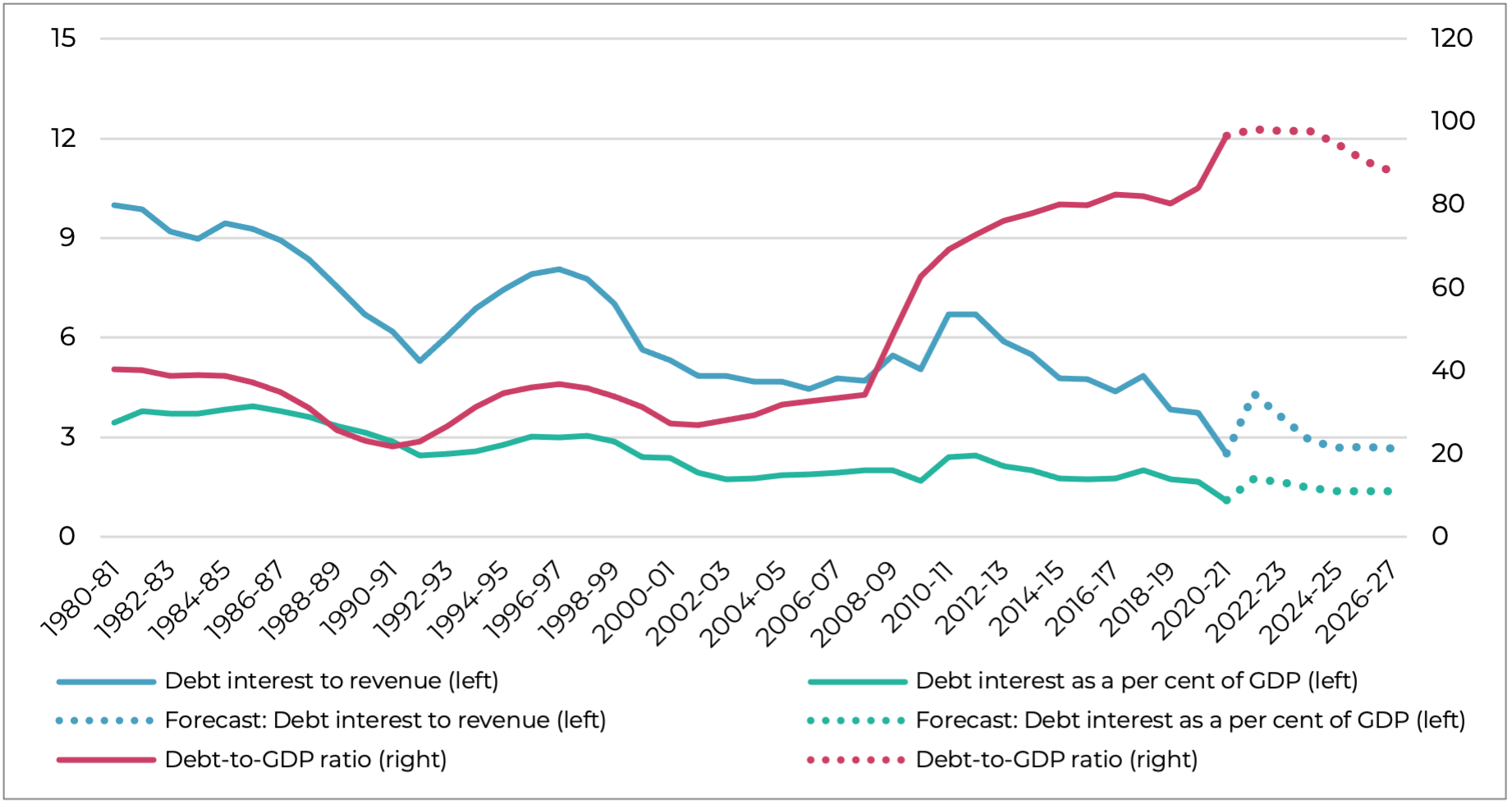

Firstly, these figures are somewhat misleading if not presented as a proportion of the size of the economy and/or a percentage of the tax take (which indicates debt affordability), alongside the wider historical context. As a proportion of the economy, debt servicing costs in 2022 and 2023 will still only be 1.6 and 1.7% of GDP and a percentage of the tax take 4.3% and 3.6% respectively — similar levels as 2018 – 2019 and still lower than at any time in the preceding three centuries (see figure below). In fact, despite inflation and higher interest rates, debt servicing costs, as a proportion of the size of the economy and tax take, will still be three times smaller than at the beginning of the 1980s.

This suggests there is significantly more headroom for borrowing to bring the economy to full output capacity by supporting the low-carbon transition and well-paid green jobs.

Spending and debt has risen significantly, but the amount spent on financing debt has fallen

Left Hand Side: Government interest payments net of asset purchase facility as proportion of GDP (%) and Debt interest as proportion to government revenue. Right Hand Side: Debt to GDP ratio (%), ex BoE, 1980 – 2026

Source: OBR 2021 & author’s own calculations

There is a separate question around whether interest rates may have to rise because of a sudden loss of investor confidence. This seems extremely unlikely given financial markets are currently extremely keen to lend to the UK government. Indeed, in its recent £6 billion sale of green gilts due to mature in 2053, the UK Debt Management Office (DMO) received £74 billion in subscriptions. That is the DMO got 12 times the amount of bids received in the Treasury’s auction versus the amount it was selling – no shortage of demand there!

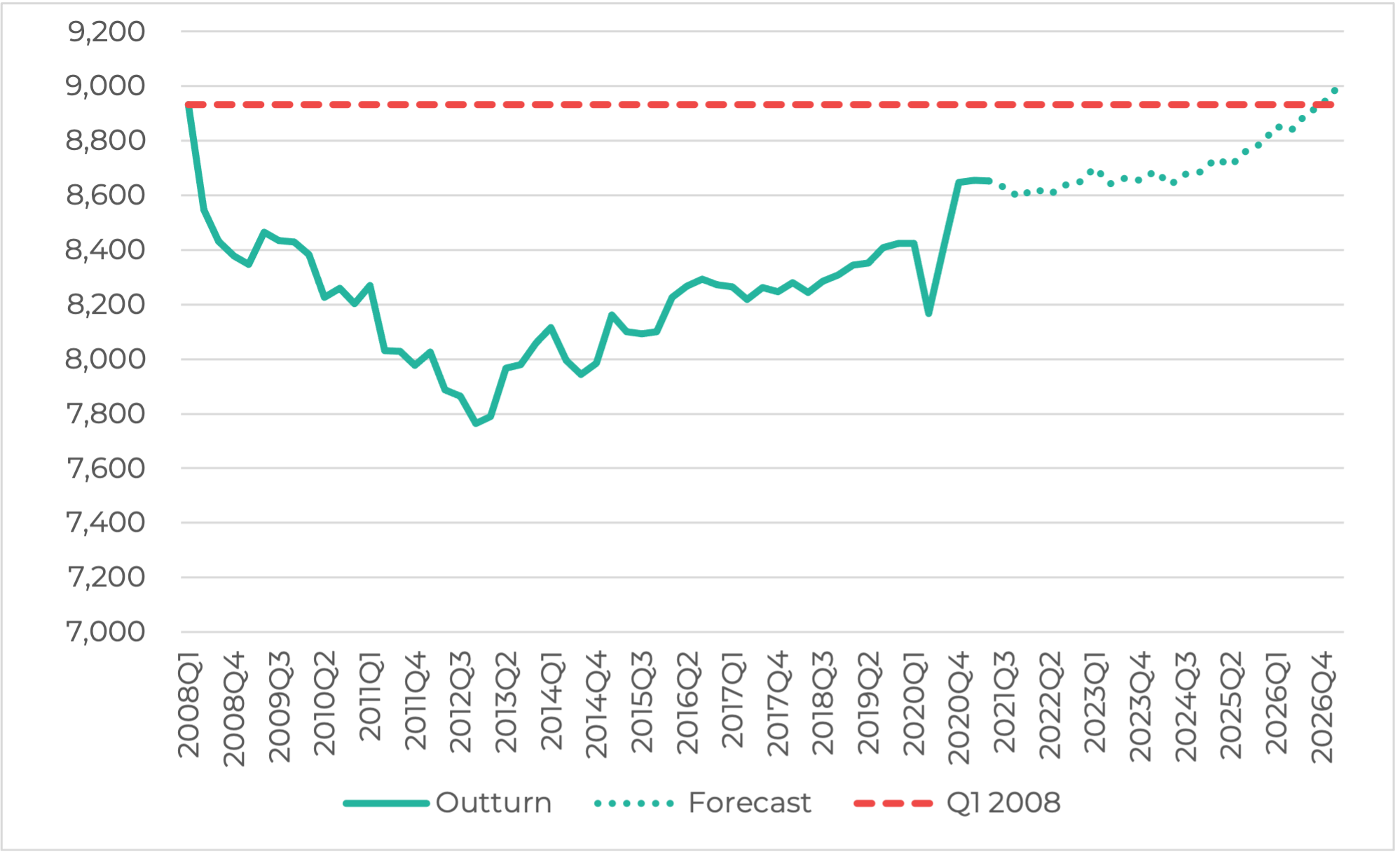

At the same time, what if the BoE decides to raise rates? The first answer is that the Bank shouldn’t raise rates, especially not past that forecasted by the OBR – in response to a largely externally conditioned supply-side crisis and given the frail state of the UK’s economic recovery. Inflation is not being driven by domestic pressures – such as an increase in wages (see figure below) and is likely to be transitory. An increase in the Bank’s interest rates will not help solve global supply chain issues, or reduce any of the pain caused by labour shortages associated with Brexit. Instead it will translate into higher costs for families who are already feeling the pain of higher prices, soaring energy prices, and declining living standards, and it will raise costs for businesses, weaken the economic recovery and possibly raise unemployment. The Eurozone learned a harsh lesson by raising interest rates too soon after the 2008 global financial crisis, it would be folly to make the same mistake.

Inflation is not being driven by sustained domestic pressure and is likely to be transitory

Average earnings (£ billions, Q3 2021 price), Q12008 to Q1 202

Source: NEF calculations based on OBR supplementary data, October 2021

However, the scenario where base rates go up beyond the OBR’s forecast, is one where the economy is recovering, jobs and household incomes are up, and overall demand is boosted. This would mean tax receipts are going up and unemployment and other income transfers to the private sector are simultaneously falling. If necessary, the BoE could deploy other credit guidance tools to curb aggregate demand, or the Treasury could raise additional taxes if needed. Finally, as a forthcoming NEF working paper will illustrate, the BoE could move towards a tiered reserve system, substantially reducing the government’s debt servicing cost all together.

Inflation and its implication for debt servicing costs shouldn’t be taken lightly. But for now, these issues are manageable, if not solvable. With an environmental emergency on our hands and a significant shortage of green investment that will only cost us more in the long run – there are other more pressing issues to keep us up at night.

Image: Pippa Fowles /No 10 Downing Street (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Topics Macroeconomics Climate change