How to close the gender pay gap for real

The latest rules on reporting the gender pay gap are welcome, but they miss the bigger picture

07 April 2017

Yesterday laws came into effect requiring companies with more than 250 employees to publish the difference between the average pay of men and women in their companies.

This is crucial information if we are to identify where women are being paid less than men to do the same jobs.

But there’s a bigger picture here about the kinds of jobs we value and those that we don’t. If we look at average pay in different industries, there’s a strange pattern whereby those who do jobs on which we all rely every day are often paid the least.

The basic economy is that which delivers the essential goods and services of everyday life – providing energy to our homes, looking after our health, educating our children and delivering food for our table.

This basic economy includes some of the poorest paid sectors in care, retail and services. Women are over-represented in many of these sectors.

Women make up 77% of the workforce in health and social work, 72% in education and 54% in hospitality. While there are also poorly paid jobs in the basic economy that are male-dominated such as fishing and agriculture, they make up just a fraction of the workforce, while education and health between them make up almost a quarter of the total workforce.

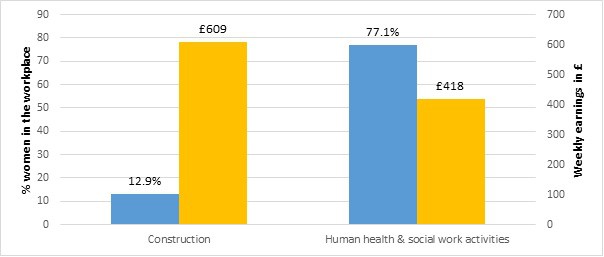

Furthermore, even industries within the basic economy that are dominated by women are often paid less. Take the two very gendered industries of construction, and health and social work. Both are professional industries made up of mostly skilled and semi-skilled jobs, but with a marked difference in pay.

Of course, if we considered the hundreds of hours of unpaid care and social work done by women, the picture would be worse again.

Understanding that women are not only paid less for the same jobs, but also paid less for doing some of the most useful and important work not only shows how urgent the problem is, it also helps us to see that individual-level responses are only going to get us so far.

The single most influential intervention on gender in the workplace of the past few years has been Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In. She argued that women should be more ambitious, more confident in their abilities and put themselves forward more often – in short, to act a bit more like men. Many responded that it would also help if men could lean out a bit at the same time, but on both sides of the debate, the focus was largely on what individuals and companies could do.

The government’s response has been along the same lines. When the Office for National Statistics launched a website comparing the pay gap within different sectors, Justine Greening argued that “this tool will empower both men and women to challenge this issue in their profession and help people to make more informed decisions about their career”.

But unless we start taking the basic economy seriously, we’ll never see gender equality across the economy. That means increasing wages and investing in high-quality training in these essential sectors, rather than relying on high-tech investment and over-paid jobs in finance to pull up average earnings.

The next few years will be crucial in ensuring the basic economy is not side-lined even further as a result of leaving the EU. But change won’t only come from government; we can also start acting now. Our work on creating good city economies shows how we can act now to put real control back in the hands of people at the local level.

Meanwhile our childcare system hurts women twice over – it is female-dominated and underpaid, but also costs so much it’s often not financially viable for women to return to work. We are helping to pilot a new model of childcare which brings costs down and improves working conditions for staff by involving parents in the delivery of care.

If we are clear-eyed about the gender pay gap, we will see that it is not enough just to make individuals and businesses act to close it. We have to support those fundamental parts of the economy which so often get overlooked. In doing so we can start to create a new economy that values people fairly and works for the benefit of all.