Leave to care: a first step to a fair system?

Overdue recognition – but the proposals come with limitations

18 May 2017

Our social care system is a leaky bucket. It costs taxpayers billions of pounds, much of which ends up in the pocket of private investors. Meanwhile half a million vulnerable over-80s receive no social care support, despite struggling to shower or even get dressed in the morning.

So it’s right that social care has been given so much attention in manifestos this week. Here we look at one of the proposals in the Conservative manifesto – giving people the right to a year of unpaid leave to care for a relative.

This proposal marks a long overdue recognition of the scale of unpaid caring for other adults. It may allow more people to stay in their own homes, reducing demand on hospitals and helping those in need of care retain some level of independence.

But the measure is limited – both in terms of time covered, and in failing to address the question of who should ultimately pay for Britain’s social care.

“Lower salary families may struggle to make ends meet if one parent took up the proposed care leave”

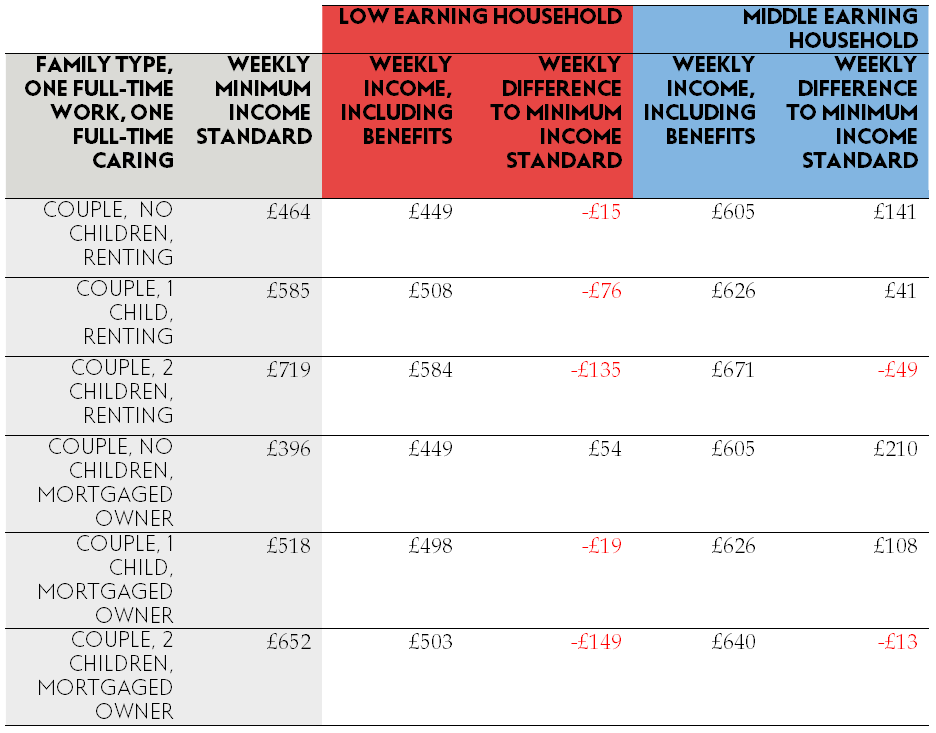

The table below sketches out some examples of how some families’ incomes may be affected if they took up a year of unpaid care leave, including estimating the benefits they might be entitled to under the current system[footnote]Assuming: renters without children live pay the median rent for a one bed flat, as recorded in 2015 – 2016 Valuation Office Agency data; renters with children pay median rent for a two bed flat; renters are entitled to the median level of local housing allowance for the corresponding bedroom size; mortgaged owners have the median housing cost paid by their family type, as calculated from the Households Below Average Income 2015 – 16 survey; council tax is the average per dwelling for 2016; the household has no savings that may affect benefits; children are 10 and 12 and the household has no childcare costs. Benefits calculated using the Turn2Us website[/footnote].

It looks at couples with and without children, where one person has taken leave to care for someone outside the household and one is working full-time. It assumes that the person caring can get Carer’s Allowance without affecting the benefits of the person they’re looking after.

It shows that for the most part, lower salary families[footnote]Defined as one parent earning the lower quartile full-time salary recorded in the 2015 – 16 Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings[/footnote] may struggle to make ends meet if one parent took up the proposed care leave, shown by comparing their weekly income with the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s Minimum Income Standard[footnote]This is the weekly amount needed to pay for necessities, as decided through research with members of the public conducted by Loughborough and York Universities. Customised amounts were calculated to correspond to the housing costs and council tax assumed in the benefit calculation. More details[/footnote].

If they have savings, they may dip into them or they may end up taking on debt to plug the gap. Renters may also find it harder than those who own their home with a mortgage due to their higher housing costs.

Middle earning families[footnote]Defined as one parent earning the median full-time salary recorded in the 2015 – 16 Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings[/footnote] may be able to absorb the hit to their finances more easily but those with two children could also struggle to get by.

Figure 1: Changes to family income through year of unpaid leave

This raises questions about our squeezed welfare system’s ability to support lower income families take up this offer. Granting a year off to care for an elderly relative could be the first step towards a care system that genuinely empowers people to make the life choices that suit them. But the devil will be in the detail.

Social care is not a question we can afford to dodge. It is right to treat the issue of our ageing society with the seriousness it deserves. We need long-term solutions that recognise the huge contributions of Britain’s paid and unpaid carers, and give people real control over their futures. A year of care leave is only a small step towards that goal. But at least it is a step in the right direction.

Topics Public services