UK workers could be owed a significant holiday

Increases in leisure time have decoupled from productivity increases

12 September 2019

New analysis at NEF has found that productivity increases appear to have translated into far slower gains in leisure time for workers since the 1980s, without a compensating increase in the rate of pay growth. Had the pre-1980 trend in rising leisure time continued, UK workers would now be working just under 13% less than they do today – which would be roughly in line with equivalent annual working hours in Germany.

Sometimes it feels as though the UK economy is trying to out parody itself. The latest suite of statistics from August made for some befuddling reading. GDP was found to have shrunk for the first time in 7 years, but despite this the most recent unemployment rate remains near record historical lows. Meanwhile monthly real earnings grew by their fastest rate since 2016 helped along by faster increases in nominal regular pay than at any time since 2008. Yet incredibly, quarterly labour productivity – the amount the economy produces per hour worked – also saw its fourth consecutive collapse for the first time since 2013.

Some part of the seemingly contradictory picture can be attributed to the unusual combination of effects and signals brought on by Brexit uncertainty. For example, one reason why Apr-Jun GDP was lower than Jan-Mar, was because GDP in the first quarter of the year received a bounce from firms stockpiling for a ‘no-deal’ departure from the European Union, some of which then needed to be wound down in the following quarter.

But a large part of the confusion is also created by the lagged relationships between different parts of the economy (productivity slowdowns, for example, can take months to feed through into real wages), and between the fieldwork period for gathering information and the statistical release date. General statistical ‘noise’ also surrounds, and can distort, attempts to draw concrete narratives from any small number of data points.

For more reliable trends, researchers need to observe longer-term data. As part of a new project at NEF, led by my colleague Aidan Harper and due to report later in the autumn we have been studying the decades’ long relationship between productivity, wages and leisure time. The lines of causation between these three economic indicators run in almost every direction imaginable, but together they offer an important gauge for how well an economy is serving the people who work in it, and in what ways (notwithstanding longer-term environmental impacts as well).

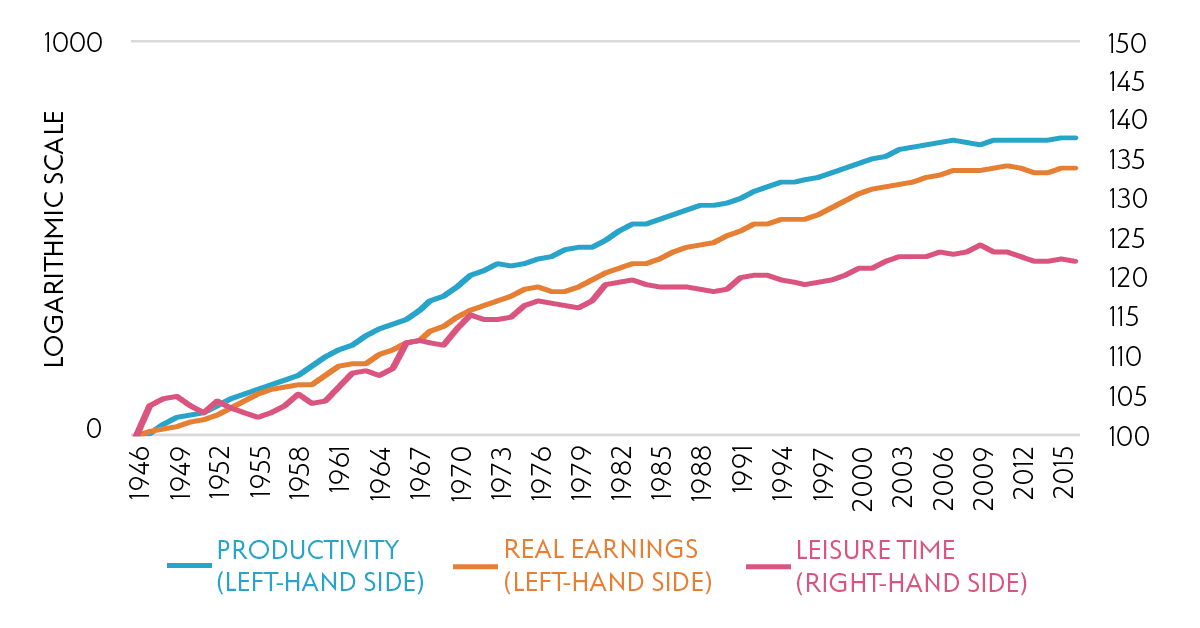

The chart below tracks these three variables back to the aftermath of WW2. It plots GDP per hour worked (productivity), earnings per hour worked (wages) and average waking hours outside of the average full-time week (leisure time) respectively over the past seven decades. All three variables have been computed using data from the Bank of England’s historical research database ‘a millennium of macroeconomic data’, and indexed to a 1946 base year so that proportionate changes across time are more easily observable.

Measures for productivity and earnings have also been plotted against a logarithmic scale – a non-linear scale where each consecutive unit on is ten times larger than the previous one – on the first vertical axis, to better reflect the marginal changes that are actually felt by people from otherwise near exponential increases in GDP and pay over time.

The evidence tells a striking story of two halves. During the decades up to the 1970s, a reasonably constant rate of increase in productivity appears to have been associated with equally consistent increases in both earnings and leisure time (see Figure 1 below). But these relationships shifted from the 1980s onwards. Despite increases in pay continuing to track rising productivity, increases in leisure time appear to peel off into comparative stagnation.

The fact that the rate of increase in hourly wages doesn’t appear to change much to compensate for slower improvements in leisure time is crucial. The implication is that, after 1980, workers benefited less overall from a given increase in productivity, but with the deficit coming in terms of fewer gains in leisure time rather than pay (unlike in the US where pay increases decoupled from productivity as early as the 1970s).

Figure 1

Since the 1980s, productivity gains appear to no longer translate into significant increases in leisure time

Respective indices for productivity, GDP per hour worked (left hand axis, logarithmic scale), average hourly earnings (left hand axis, logarithmic scale) and leisure time for full-time employees (right hand axis), 1946 – 2016, 1946=100

Source: NEF calculations using Bank of England (2018) ‘A millennium of macroeconomic data’ https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/statistics/research-datasets

NB: for leisure time we use a proxy based on the average hours worked by those in full-time employment subtracted from 84, which we take as a constant for average weekly waking hours

One explanation for the trends presented above are the choices made by government, politicians and policy makers. During the three decades following World War Two, strong collective bargaining and increased labour market regulation likely contributed to stronger rewards for workers per unit of productivity increase. But since the 1980s, this may have faltered due to less well-regulated labour market conditions and reduced union representation.

Testing this hypothesis thoroughly would require a more sophisticated analysis capable of estimating the precise relationship between leisure time and productivity during the two time periods respectively – and after controlling for a host of other relevant economic and policy variables (such as interest rates, employment or income inequality) beside just average wages.

This notwithstanding, and taken at face value, the evidence appears important. The UK works among the longest hours of any country in north-western Europe, with Germany leading the way in terms of the fewest average annual hours worked – a full 13% lower (NEF analysis based on OECD data) compared with those in the UK (both cause and effect of Germany’s higher levels of productivity).

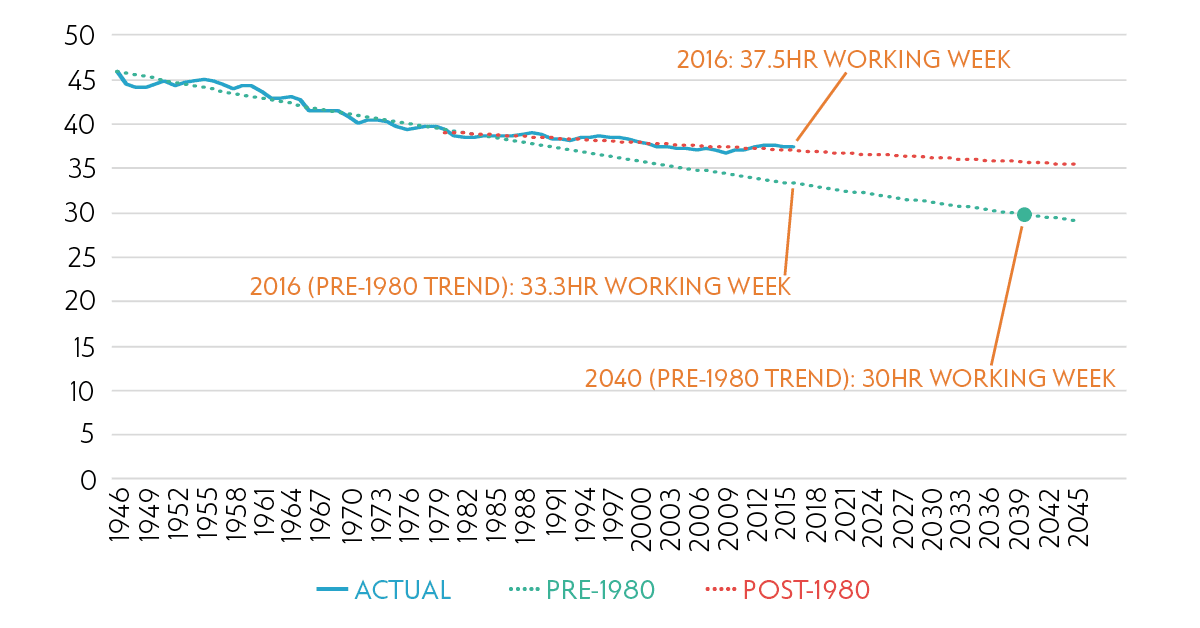

But if the pre-1980 trend in increased leisure time had continued uninterrupted in the UK, workers would now be working just under 13% less than they do today – by coincidence, this would be broadly in line with equivalent annual hours in Germany (see Figure 2 below). Furthermore, if the same trend were to have continued deeper into the 21st century, the UK would have been on track to work 20% less by 2040 compared with 2016 levels. Or in other words, the equivalent of a 30-hour – or ‘4‑day’ – working week.

Figure 2

If the pre-1980s trend had continued, the UK would be on course to reach the equivalent of a 30hr week by 2040

Average weekly hours for full-time employees, with both the pre-1980 and post-1980 trend lines, 1946 – 2045

Source: NEF calculations using Bank of England (2018) ‘A millennium of macroeconomic data’ https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/statistics/research-datasets

NB: projected trend lines based on simple bivariate regression

The stylised analysis above suggests that significantly reduced work time is not beyond the realms of plausibility. Indeed, in the UK’s recent past, increased productivity gains were commensurate with rising leisure time at a rate consistent with reaching a 30 hour full-time week in the first half of the 21st century.

Over the most recent decade, however, annual increases in productivity has collapsed by around two thirds compared with the previous forty years – compounding the UK’s position as one of the least productive countries among advanced economies globally. The immediate challenge then is arguably almost as much about returning to greater improvements in productivity, as it is about how the benefits of these gains are distributed. Recent NEF analysis has shown that a substantial part of the problem is a lack of aggregate demand – the total amount of spending in the economy – caused by a combination of inequality, austerity and Brexit among other things.

But in this respect, and if done in the right way, reduced working time could also be part of the solution: since increasing leisure time while protecting pay can be expected to increase spending in the economy overall.

Reduced work time can be driven in a number of ways, including from the bottom up involving negotiation between workers and employers, and from the top down via direct and indirect policy support from government. On the latter of these approaches, NEF recently proposed the introduction of a new working time commission, which would make official recommendations to government on regular increases to annual statutory paid leave, and on a similar basis to work done by the Low Pay Commission in the UK today.

Initially, this new commission should be tasked with recommending increases in statutory leave that are as large as possible – subject to not increasing unemployment – so as to maximise demand in support of higher productivity. But over time, the objective should shift to slower, more consistent increases in paid leave that help to ‘lock-in’ a dynamic where workers are automatically rewarded for sustainable increases in productivity with more paid time off, and alongside wage increases as well.

With the current UK economy and labour market in a state of Brexit induced turmoil, it can be difficult to see the wood from the trees. But the failure to remunerate workers fully for rising productivity over decades is also potentially one of the reasons we find ourselves where we are today. In any case, Brexit or not, it’s possible that UK workers could be owed a significant holiday.

Image: Unsplash

Campaigns Shorter working week

Topics Work & pay Macroeconomics