The true scale and impact of benefit cuts for ill and disabled people

NEF analysis shows the cuts will hit ill and disabled people by almost £2bn more than what has been widely reported

31 March 2025

Documents published alongside the spring statement last week, revealed the true scale and impact of the government’s benefit cuts for ill and disabled people — but only if you knew to look beyond the headline figures.

The widely reported numbers were concerning enough — £4.8bn of cuts would lead to 250,000 people being pushed into poverty, including 50,000 children. However, the way these figures have been presented has concealed the reality. NEF analysis shows that these cuts will hit ill and disabled people by almost £2bn more than the reported figures and could see around 100,000 additional people pushed into poverty.

The headline figures downplayed the scale and impact of these cuts by factoring in the decision not to proceed with a policy announced by the previous government and pencilled in, but never fully confirmed, by this government. This policy would have changed the Work Capability Assessment (WCA) to make it harder for people to qualify for a higher rate of universal credit (UC) on the basis of illness or disability.

Ever since the previous government’s consultation on these plans was struck down in the High Court, it had seemed unlikely that the changes would proceed as planned. This government’s green paper revealed that the WCA would be scrapped altogether in 2028 and that they would not implement the previous government’s planned changes ahead of that.

This allowed them to claim that they would effectively be “spending” £1.6bn (what they were projected to save if the policy had gone ahead) and lifting 150,000 people out of poverty, by not implementing a change that hadn’t even got past an initial consultation phase. As the Resolution Foundation pointed out:

“In strict scorecard terms, this is the correct approach, but as it represents the cancellation of a never-implemented cut, it will never be felt as a positive impact by households and we do not consider it further [in our analysis].”

To put it another way, using this phantom policy to offset the scale and impact of actual cuts happening in the real world is akin to suggesting that you should feel better off because your boss had thought about cutting your wages but then decided against it.

Rejecting this accounting trick allows us to gain a clearer picture of how ill and disabled people will be affected by the government’s plans. Figures from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) show that changes to the personal independence payment (PIP) assessment and cutting the health top-up in UC will see ill and disabled people lose out on £7.5bn by 2029 – 30.[i] This will be offset slightly because this group will receive around 43% of £1.9bn being spent on increasing the basic rate of UC, bringing their total cuts down by £800m to around £6.7bn.[ii]

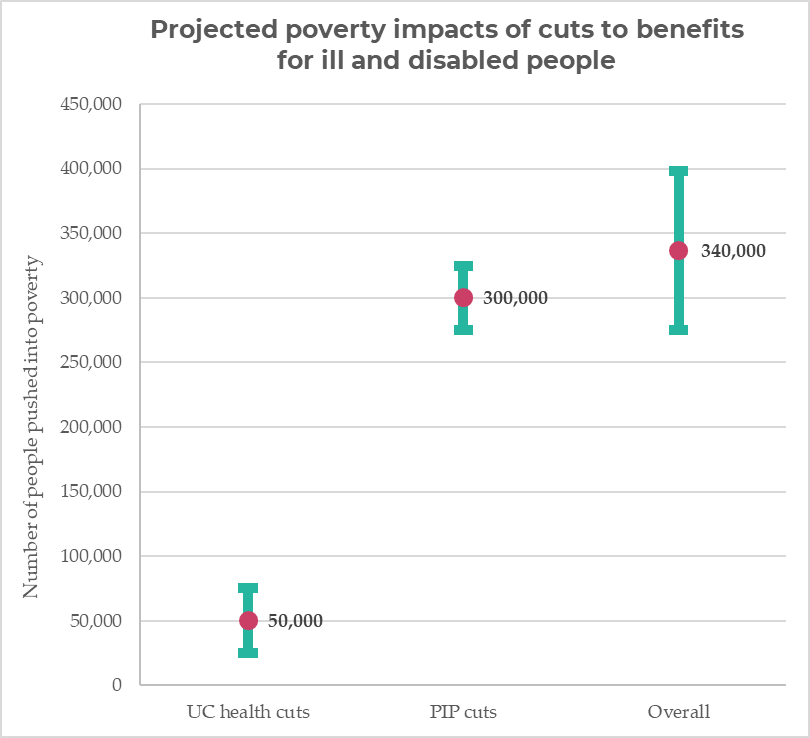

When it comes to the effect of these cuts on poverty, discerning the true impact is difficult. The Department for Work and Pensions’ (DWP) impact assessment suggests that the changes to the PIP assessment will push 300,000 people into poverty, while the cuts to the UC health top-up will have this effect on 50,000 people. However, these figures are (unhelpfully) rounded to the nearest 50,000, meaning the actual impact of each of these changes could be 25,000 either side. Furthermore, the document flags that the two cuts will impact some of the same people, which means we can’t simply add these two figures together.

That leaves us with a range for the potential impact of each policy, and an even big range for the combined impact. But taking the middle of these ranges, we estimate that the likely cumulative impact is around 340,000 additional people pushed into poverty.

The government has argued that any projected rise in poverty should be treated with caution, because they expect it to be mitigated by more people moving into employment. They make this claim primarily in reference to additional planned investment in employment support, but their narrative has also implied that the cuts themselves are a necessary part of “encouraging” more people into work.

However, the government is yet to produce any estimates or evidence of how many ill and disabled people will return to work as a result of their reforms. Meanwhile, the OBR reports that they received too little robust information from the government to make their own assessment.

Politicians and the public are therefore being asked to support cuts to benefits for ill and disabled people, and a consequent rise in poverty, both of which have effectively been understated in government and OBR figures, on the promise of better employment support (and an assessment of its likely impact) at some point in the future.

Returning to the reality of how these cuts will be experienced by ill and disabled people, we know from our research that hardship, anxiety around losing benefits and the threat of conditionality all fundamentally undermine the sort of genuine engagement with employment support that leads to people overcoming barriers and returning to work. The government may want to present these cuts as being consistent with the promising reforms to employment support announced in last year’s white paper, but the truth is that they are contradictory and incompatible agendas.

Footnotes

[i] We have not included the £200m and £300m that is projected to be saved through more frequent reassessment of those on PIP and the UC health top-up respectively, because it is debatable whether these constitute ‘cuts’. However, many of these reassessments may lead to ill and disabled people losing out despite experiencing substantial barriers and additional needs.

[ii] This 43% figure was arrived at through data included in DWP’s impact assessment of the cuts, which shows that, by 2029 – 30, the UC caseload is projected to be 6,890,000, of which 2,980,000 will be in receipt of the health top-up

Topics Social security