The financialisation of UK homes

The housing crisis, land and the banks

21 April 2016

Average UK house prices are nine times incomes across England and Wales, and up to 20 times incomes in London and the South East. Why? In seven steps we explain the role of banks, supported by government policies — and point to some ways to cool the crisis.

We hear so often that house prices are rising because supply has not kept pace with demand. But tackling just the supply side of this equation will not stabilise prices.

We also need to take a closer look at what is fuelling demand. Demand is a combination of the desire for houses (the number of buyers in the market and the strength of preference that they feel) and the purchasing power that these buyers wield. Both elements have risen to unsustainable levels.

1. Why do people want to own homes?

The preference for home ownership has increased for a number of reasons. Other housing options are increasingly unviable: tenants want to escape poor-quality, insecure and overpriced rental properties, while social housing is being sold off and not replaced.

The expectation of future price rises has also changed how we think about property. Houses are no longer regarded as simply somewhere to live, but an investment that offers long-term financial security in the face of stagnating wages, dwindling pensions and reduced welfare provision. Unlike other types of unearned income, profits made on your home from rising prices are not subject to capital gains or windfall taxes.

People wanting to own their own home increasingly have to enter a bidding war with speculative buyers. These include not just wealthy overseas investors, but also asset-rich baby boomers taking out loans against their homes to invest further in the property market, often as buy-to-let landlords.

2. Where do people get the money to buy these expensive houses?

The prime source of purchasing power in the housing market is bank loans – in the form of mortgages – rather than people’s pay packets. The more banks are willing to lend, the more money floods into the housing market.

This is one of the key reasons that prices have been able to race ahead of most people’s wages.The credit that banks lend for mortgages is not money in someone else’s savings account, but new money created specifically to fund the loan. As banks become more and more willing to grant large mortgages, the supply of money to the economy — and therefore purchasing power — increases.

3. Why are banks prioritising mortgage lending?

In recent decades, banks in advanced economies have begun to lend more and more against property, mainly in the form of domestic mortgages. A recent study in 17 countries found that the share of mortgage loans in banks’ total lending portfolios has roughly doubled over the course of the past century. The UK is a prime example, with domestic mortgage lending expanding from 40% of GDP to 60% since the 1990s.

It was the deregulation and liberalisation of the credit market in the 1970s and 1980s that kick-started the shift towards this preference for mortgage lending over other activities, as banks and building societies were for the first time allowed to grant credit to households against the value of their homes. Previously, only building societies, controlled by their members, were permitted to issue mortgages.

Image credit: Elliot Brown via Flickr

Image credit: Elliot Brown via Flickr

Since this deregulation, the UK finance sector has changed considerably. Banks have merged and grown bigger, developing a more hands-off, centralised approach to their lending activity. Automated credit-scoring techniques are used to make loan decisions and alongside this, banks have developed a strong preference for securing lending against collateral, in particular property.

The incentive for this preference is clear: If a bank lends against a property and the borrower doesn’t keep up their repayments, the bank ends up with the house and the land it sits on. Other forms of lending require more involvement on behalf of the bank and are simply riskier: if a bank lends to a business and the business goes bust, the bank gets nothing.

With the majority of UK loans now funding mortgages, most new money in our economy is being pumped into land and housing.

4. How does the demand for houses affect supply

The high level of demand in the housing market has had a huge impact on the price of land. In fact, three quarters of the rise in UK house prices since the 1950s can be explained by rising land prices6 – and there is a self-reinforcing cycle at work that keeps these prices high.

If land costs a lot, stakes are higher for developers wanting to acquire it to build on, because the project will cost them more overall. As such, the prices of the homes they build have to be higher for the developer to turn a decent profit. The risk with building lots of new homes in a particular area is that it could have the effect of lowering prices. There is therefore a perverse incentive for developers to trickle out housing supply, in order to keep local prices up.

5. Can prices keep rising forever?

If the growth of mortgage lending outpaces the supply of new homes, then prices will inevitably continue to rise: there is more money chasing the same number of homes and so prices inflate.

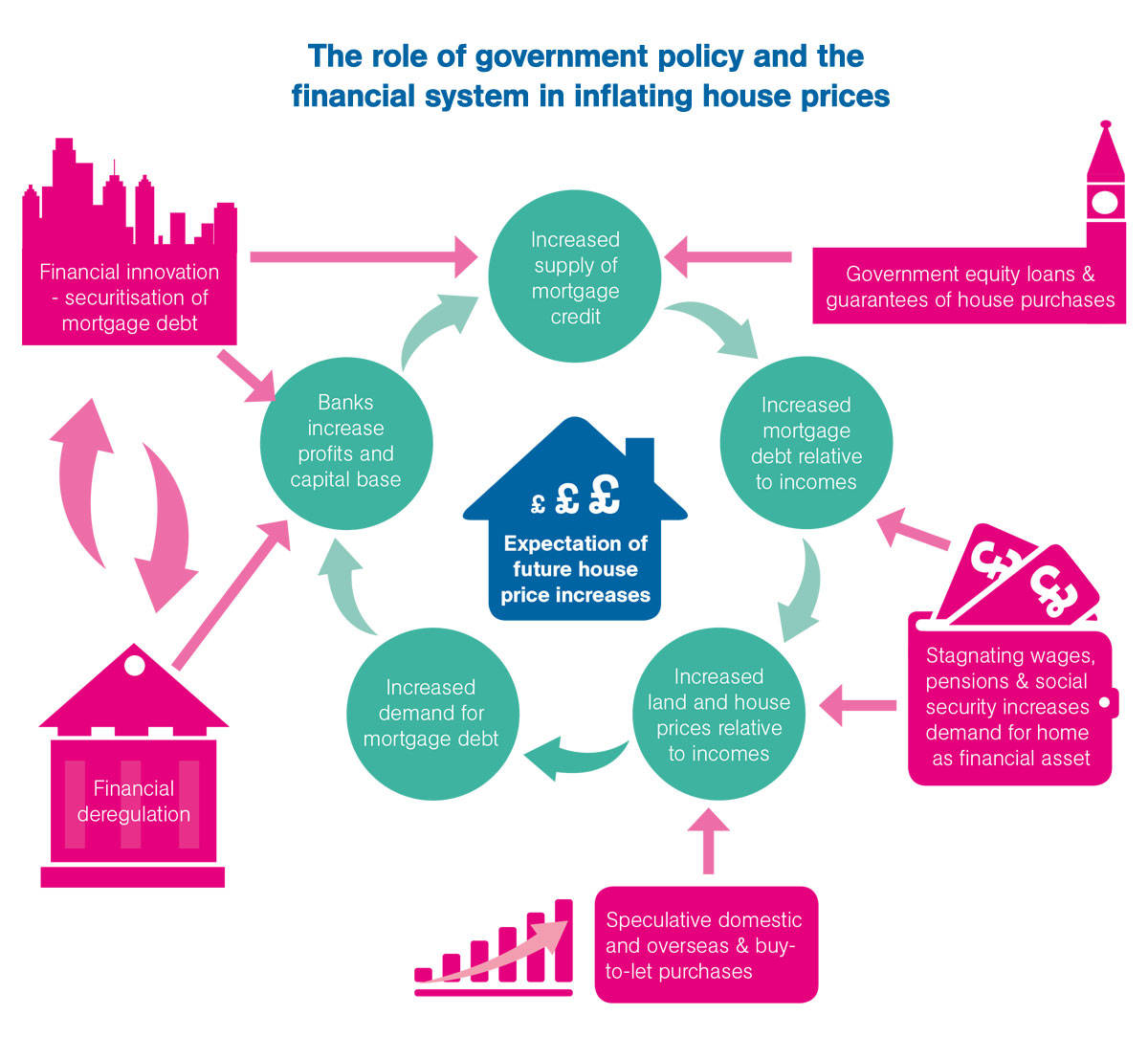

The cycle goes like this: as land and house prices rise, households are forced to take out larger mortgage loans to get on the housing ladder, boosting banks’ profits and capital. The boost in profits and capital enables banks to issue more loans, which further pushes up prices. This process can continue even when house prices are many times people’s incomes, sustaining the expectation that prices will rise, as laid out in Figure 1.

Is there a breaking point? The process can continue until there is an economic shock and people’s incomes can no longer keep up with debt repayments. Indeed, as the ratio of house prices and mortgage debt to income increases, the economy becomes more vulnerable to any change that would spark a larger portion of people’s income to be taken up in debt repayments on their mortgages: such as a fall in salaries or rise in interest rates.

Such a change, if significant enough, would see the whole process goes into reverse: mortgage defaults, falls in house prices and therefore in people’s net wealth. This would spark a contraction of bank lending, a recession in spending and, potentially, a financial crisis.

6. What are the wider economic risks?

For those lucky enough to own homes, rising prices give the feeling of rising wealth and encourage more spending (the “wealth effect”). Unsurprisingly, this wealth is not evenly distributed across the population. The wealthiest 10% have an average of £420,000 worth of property — compared with the least wealthy half of the population who have negligible or no property wealth, either because they are renting, or because their mortgage accounts for such a large share of the value of their property.

Because of the interrelatedness of house prices and our nation’s spending patterns, it is not only home owners who might fear a change to the current system. Household spending contributes around two-thirds of GDP growth in the UK, and therefore the purchasing power of the population is vitally important for the UK’s wider economic health.

If an unplanned housing downturn prompted people to tighten their belts, economic activity is likely to slow.

It is therefore hardly surprising that the first thing the former coalition government did to try and boost spending and the economy post-crisis, was to boost house prices and home ownership by subsidising mortgages via the Help-to-Buy equity loan scheme.

But the growing preference for mortgage lending comes at the cost of funds for the productive economy – loans for business expansion, infrastructure and the job creation that comes alongside it.

In aiding the creation of an economy that runs off mortgage debt rather than through boosting spending power via increases in wages, productivity and trade, we’ve become entrenched in a housing affordability crisis with a great human cost. The burden of mortgage debt is now increasingly falling on the shoulders of the young, much more so than any other time in the last 20 years.

Soaring house prices are not just a problem for first time buyers wanting to buy a house. They create a powerful financial incentive for people to “overconsume” the housing we have whilst directing government spending away from supporting real housing needs.

The result is a widening of the gap between the housing haves and the have nots. Families paying social rents are being shipped out of areas of rising prices as the land their homes sit on is sold to developers. Overcrowding is becoming prevalent and there has been a 55% rise in street homelessness since 2010.

7. How do we fix this?

Mortgage debt cannot outgrow incomes forever, even if it is subsidised by governments. At a certain point, people will begin to cut back as more and more of their wage packets are taken up with mortgage repayments. Rather than waiting for this inevitable crash, is a different path possible?

NEF is working with campaigners, researchers and policy-makers to develop proposals that will stabilise house prices and ensure we have sufficient good-quality homes for the developing needs of the population. Three areas we will focus on:

1. Achieving a pluralism of housing models and improving options for debt-free homes across the UK

- Support the growing tenants’ movement to professionalise the private rented sector, making it more secure and priced according to people’s incomes

- Boost the stock of non-market housing including homes with social rents and community-led schemes, and develop new models of no-debt or low-debt ownership

- Rebalance demands on space with regional development strategies and investment in jobs and infrastructure outside London and the South East

2. Detering speculative investment in property and land

- Develop a new tax to capture the rising value of land for the public good

- Support schemes where land is held by either a public body or community, separating the cost of land from the cost of homes

- Develop secure, attractive pensions and alternative savings and investment options, to reverse the growing dependency on housing wealth to pay for retirement and old age care

3. Building a more diverse banking sector and tackle excessive mortgage credit

- Ensure banks hold more capital against mortgage loans and keep the loan until maturity, rather than packaging up and selling on

- Build a mortgage market that serves principally to enable people to organise their finances for the long term, for example by removing teaser rates, interest-only periods and by favouring loans with long-term fixed interest rates

- Reduce banks’ preference for mortgage lending by diversifying the financial sector to include public and other stakeholder banks

Topics Housing & land