Why the Bank of Mum and Dad is another sign of trouble in our housing market

Britain's broken housing is driving a wedge between generations

02 May 2017

Figures released today show that parents are set to lend more than £6.5bn this year to help their children get on the property ladder, making the ‘Bank of Mum and Dad’ the UK’s ninth-biggest mortgage lender.

The figures are revealing: a further, troubling sign that the UK’s broken housing market is driving a wedge through society.

Today a whole generation finds itself priced out of the market, struggling to make ends meet in the face of eye-watering rents. Millions of people feel they lack control over one of their most basic needs.

Average house prices are now on average nine times that of incomes across England and Wales, and up to 20 times incomes in London and the South East.

Levels of homeownership have been falling rapidly for fifteen years, particularly among young people. While in 1990 63% of those aged 25 – 29 owned their own homes, today it has fallen to 31%, and is still falling.

How did we get here?

Successive waves of ill-thought-out housing policy, changes in welfare and taxation and financial deregulation have resulted in land and housing in the UK becoming ‘financialised’.

The normalisation of double digit house price growth, combined with the expectation that house prices will continually increase, fuelled demand for houses as financial assets. Whereas fifty years ago houses were simply regarded as somewhere to live, today homeownership is viewed as a means of accumulating wealth and long-term security in the face of stagnating wages and dwindling pensions.

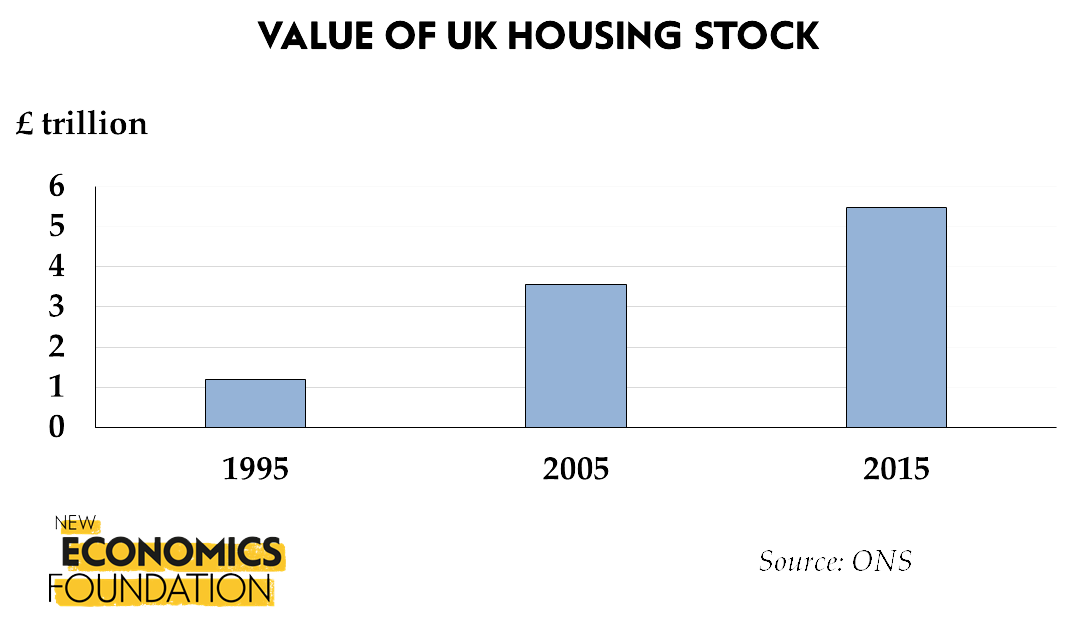

Today the value of the housing stock stands at £5.5 trillion – around 60% of the entire net wealth of the UK. This has increased from just over £1 trillion twenty years ago.

For those owning property, this has generated an unearned windfall gain which has increased net wealth. This has brought greater economic security – housing equity can be converted into income via home equity withdrawal, increasing spending power for a new car or holiday, or it can be used to leverage up further, perhaps buying a second-home, or entering the Buy to Let market.

But for those who do not own property, this has meant higher rents in the rental market, or having to save more for a mortgage deposit. So while rising house prices may make individual owners wealthier, society as a whole is no better off because, nothing new has been produced.

“The housing boom has come at the expense of younger generations who do not own property, who will now see their incomes eaten up by higher rents and mortgage payments”

In some lucky cases, people will be rescued by Mum and Dad as housing wealth is passed onto some of the next generation. Realising their children will never have the opportunity they had, parents provide children with a lump sum – or indeed hand over the keys to a second home – to give them a foot up onto the housing ladder. The big banks have been capitalising on this intergenerational wealth sharing with Bank of Mum and Dad mortgages. But for the majority of people this is not an option. Increasingly, the key dividing line running through society is not earnings, but access to property ownership.

Unfair and inefficient

Not only is this not particularly fair, it’s also not particularly efficient. By sucking up so much more of our income and savings, soaring land and housing costs diverts resources from much more productive uses.

This is the topic of a major new book by the New Economics Foundation, in partnership with publishers Zed Books: Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing.

In the book we show how many of the key problems facing the UK – including the housing crisis, deepening inequality, poor prospects for sustainable growth, intergenerational conflict, low productivity and financial instability – are all linked to a dysfunctional land market.

Looking at the ways in which discussions of land have been routinely excluded from both housing policy and economic theory, we make the case for urgent action to fix the problem.

What needs to happen?

Empty rhetoric about building more houses is simply not enough. Creating a fairer and more sustainable economy requires bold changes. We outline how policymakers should seek to give people back control over housing by:

- Making housing supply less dependent on the volatile private market in land and homes by halting the public land sale and boosting the stock of non-market housing

- Levelling the playing field between tenures so that people are not incentivised to overinvest in homeownership

- Capturing the uplifts in value of land for public benefit through taxation and more strategic use of public planning and purchasing powers

- Establishing new sources of low-cost finance for construction of new housebuilding

- Reducing the reliance on housing market as a means for accumulating wealth, paying for retirement, or funding care in old age

- Breaking the positive feedback cycle between the financial system, land values and wider economy

Topics Housing & land