Bailouts: creating the new normal

Bailing out struggling companies shouldn’t mean a return to business as usual after Covid-19.

27 April 2020

They say we should have put the economy on ice and frozen every business’ balance sheet the moment the lockdown began. Once the crisis came to a close we could have flicked the switch back on. Normality would have resumed.

Or would it? More importantly, is that what we want?

It is becoming increasingly apparent that the government’s primary crisis support mechanism, the Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme (CBILS) won’t be enough to prevent a private sector meltdown. The scheme currently only underwrites 80% of each loan’s value and doesn’t cap interest rates. This, coupled with the government’s reliance on profit-seeking intermediary banks to distribute loans and the lax regulation of those banks means money is not getting to the firms who most need it. Even for those businesses lucky enough to receive a loan, major question marks remain over their ability to make repayments in the long term. Business will need more support, and on more generous financial terms. Bailouts are on the cards.

Different kinds of businesses pose different bailout challenges and a debate has already begun regarding what form bailouts should take, and what the government should expect in return. Right now, it doesn’t make sense to attach strict conditions to support for smaller businesses. This is partly because such firms are so numerous (there are 5.9 million small and medium-sized businesses in the UK, if defined as companies with less than 250 employees), and there is only limited policy and administrative bandwidth to monitor and enforce conditionality. But more importantly, for many of these companies, time is of the essence – they need immediate support if they are to survive. For smaller companies then, the urgent priority is to reform the CBILS so that all companies who need support can get it, without being saddled with unserviceable debts.

For larger businesses, for example those with over 250 employees or with turnover greater than £45 million, the context is different. In general these companies are more likely to have the time and resources to engage with any conditions that are attached to support. More importantly, larger firms offer greater bang for buck with limited government bandwidth – 8,000 large companies (as per the definition above) account for 40% of the workforce. Attaching conditions to support packages for firms like this makes greater strategic and pragmatic sense.

Bailouts must reflect the wider need for a system shift

In constructing any conditional bailouts, we should learn the lessons of the 2007/08 financial crisis. Its legacy is at best one of missed opportunities to reform a fundamentally failing financial system, and at worst one of state-administered damage to worker wellbeing and exacerbation of extreme income and wealth inequality. The government must take urgent steps to lay down a robust framework which ensures big business bailouts deliver wellbeing for people in the short term, and lays the foundations for a more equal, more sustainable post-coronavirus economy.

The decade of economic stagnation that followed the last recession too often featured greedy, extractive, and short-sighted business practices. Underneath the hood of the UK’s productivity problem are issues caused by short-termist attitudes in firms’ corporate governance: such as share buy-backs, skyrocketing executive pay, profiteering from public services, underbidding on contracts, and overexposure to financial risk. Reforming corporate governance so that firms are more able to take a long-term societal view should be high on the agenda for bailout conditions.

On the other side of the coin is a decade-long assault on the quality of work. Use of temporary and often exploitative hiring and contracting practices has proliferated. Over five million workers (one in six) have insecure jobs. The UK has gone through its most sustained hit to living standards in a generation. Weak productivity and pay have helped lock-in high levels of household and regional inequality. Many large businesses whose shareholders have benefited from these recent economic trends operate in sectors, including hospitality and social care, which are now at the sharp end of the Covid-19 crisis. Improving working conditions in these sectors should be a high priority for any conditionality attached to government support.

Alongside concerns over the quality and distribution of work, productivity and profit, the climate crisis is becoming more urgent by the day. If we are to meet our international commitments, economic restructuring towards zero-carbon living can’t wait any longer. Critically, this means an end to public and private attempts to ‘net out of jail free’ – delaying any emissions reductions in favour of promising impossibly high rates of future offsetting. Our bailout programme must address the elephant in the room regarding the future makeup of high-carbon industries such as aviation, surface transport, and agriculture.

The present turmoil in the fossil fuel energy market may offer an important opportunity. Crude oil prices have hit their lowest level in history as, coming off the back of an international price war, Covid-19 has caused energy usage and road mileage to plummet. The World Economic Forum are speculating that depressed energy prices could “eliminate” coal as a fuel altogether. The high-carbon energy industry faces a reckoning and a highly uncertain post-Covid future. We can’t miss this opportunity to use bailouts to restructure how companies work and coordinate a just transition for workers.

Frameworks for conditionality

Bailout conditions can be used to deliver positive change in strategic areas like business culture, quality of work, and decarbonisation. But such conditions won’t be ‘one size fits all’. The government has multiple tools at its disposal when it comes to getting a fair return for public support, each appropriate to achieving different social or environmental policy objectives.

At the simplest end of the spectrum will be firms in sectors which do not need fundamental overhaul in order to comply with social and environmental objectives. This includes businesses in hospitality, universities, and the arts. The government should still expect its bailouts to return improved employment standards in particular, plus better corporate governance and reduced carbon emissions over the longer-term. But for these sectors, meeting these conditions should be possible under present private ownership models. In these cases the government has the option of taking a minority equity stake in bailed out companies. To speed up the process the government could only use conditionality to ensure workers don’t lose their jobs. Longer-term business policies could then be influenced through public shareholder power in existing corporate governance structures.

Some commentators have suggested a minority stake model is workable as a blanket approach to most bailouts. Government holdings could be transferred to a sovereign wealth fund which can be managed for the long-term national interest. However, the government also has an interest in generating income for the Treasury, and some of the businesses now requesting bailout may represent very high-risk investment prospects. In these cases the government might protect its interest by taking a position as senior creditor of a conditional loan.

In other cases the government will have wider interest in businesses and sectors for their role in its industrial strategy. The most obvious examples include businesses with key roles to play in decarbonisation (for example aviation and bus transport), and businesses which provide public services (for example social care and child care). As a minority stakeholder or creditor the government may find its strategic aims coming into conflict with the profit motives of other business investors. Instead, the government could be in a better position to achieve its aims via a majority stake. From this position corporate governance can override the profit motive, even if just for a transition period. The most obvious examples are in the social care and transport sectors, which are likely to undergo significant transformation as a result of Covid-19, changing demographics, prevailing public attitudes and the need to decarbonise.

In some more extreme cases, particularly the fossil fuel sector, the government has a motivation to see the managed decline of entire subsectors. In this instance there is likely a negative financial implication to the government’s intervention. But due to the overriding priority of securing a just transition for workers in these sectors, there is a strong case for full nationalisation of these businesses. This would mean the government could directly steer a managed decline in the fairest possible way. In some cases the costs of nationalisation might be mitigated during the valuation process by considering the government’s past and future financial support to the business through preferential tax arrangements.

Nationalisation does not necessarily mean bailout in the traditional sense, as the business itself may be left to fail, but it is imperative that the workers’ jobs are protected for as long as possible. Some form of workers’ bailout might be appropriate, in which the government adopts and honours workers’ contracts while giving time and support to enable retraining and new job creation elsewhere.

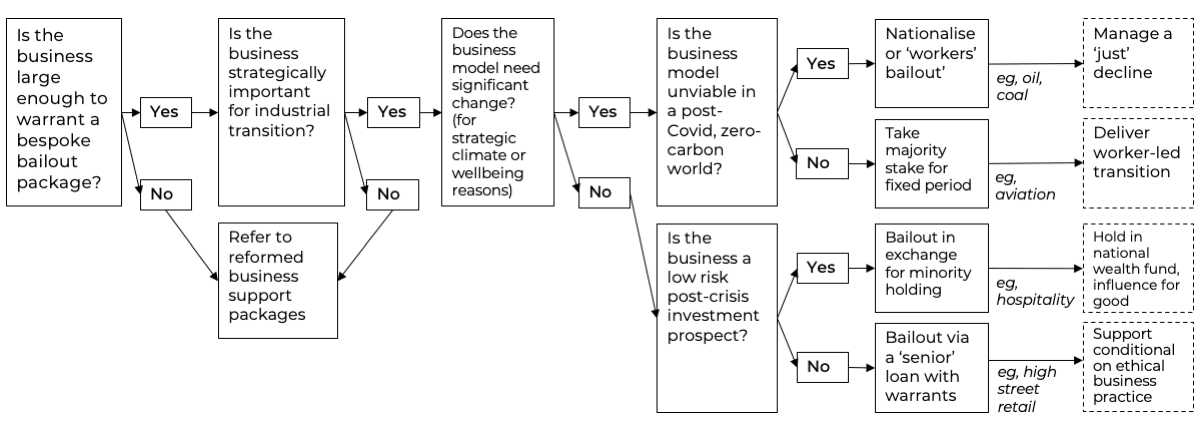

Below we present a simplified decision tree which illustrates how some of the various considerations with regard to a bailout process might be made. In the coming weeks at NEF we will be proposing a more detailed framework for fair bailouts, but this diagram provides a preliminary structure with the intention of stimulating discussion and debate.

Figure 1: A possible framework for decision making on bailing out businesses (enlarge)

Companies are facing widespread insolvency, and bailout packages are technically complex. This means the government will need a tight framework for bailout activity. It will also need a dedicated body to oversee its framework, which is at least partially insulated from the cacophony of the wider Covid-19 crisis. Social and environmental outcomes do not follow automatically from central government ownership. Even at this early stage the government should have its eye on the longer-term management of its bailouts, and how they influence the balance of power between workers and owners during and beyond the government’s financial commitment. Without careful management to ensure they apply fair bailout principles, the government risks being overtaken by the scale of the crisis. Take our eye off the ball, and short-termism will prevail and the mistakes of 2007/08 will be repeated. The government must use its financial powers to build the world we want, not rebuild the world we had.

Image: Pexels

Campaigns Coronavirus response