Job Support Scheme leaves two million jobs unprotected

Scheme likely to protect just 17% of jobs at risk from redundancy.

21 October 2020

Update 28 Oct 2020: After this research was published, the Treasury announced significant improvements to the Job Support Scheme. The Financial Times reported: “Officials had read a carefully researched report by the New Economics Foundation, which warned that 2.2m jobs were at risk under the original version.” Under the revised scheme the government will fund 62% of pay for hours not worked, rather than 33%. But the government must go much further to prevent millions from facing real hardship this winter. NEF will publish full proposals during November.

Last month, under significant pressure from businesses, unions and communities across the UK, the Treasury ended its stubborn resistance to extending furlough. From the end of October we will have the Job Support Scheme (JSS) – the policy which, in theory, stands between us and perhaps one to two million people becoming unemployed. But new NEF analysis shows the JSS is likely to protect only a small fraction of the number of jobs currently at risk of redundancy, and paints a bleak picture for communities across the UK.

Bolted on top of the JSS is what is being termed ‘expanded’ JSS, a scheme which is more generous to employers but less generous to workers, which will provide support to employment costs in areas placed in full lockdown. However, the ‘expanded’ version of the JSS is only available to employers during temporary enforced closures, and does not provide support to business supply chains. As such, the JSS remains the baseline level of support which most businesses will use to calculate the viability of retaining employees.

A critical pillar of the government’s rhetoric around the JSS is that it will support so called ‘viable’ jobs: jobs that may return to full productivity when the infection rate begins to fall. As a result, and as others have already pointed out, the JSS is a far less generous scheme than its predecessor, the Job Retention Scheme (JRS). This is both in terms of overall salary protected and, more importantly, the level of employer contribution towards salary costs. Such is the level of employer contribution, that even where they can claim the £1,000 Job Retention Bonus, the direct costs of keeping two employees working part-time (50% hours) on the scheme are often higher than keeping one employee working full-time (100% hours) and firing the other.

One feature of the JSS is that it performs better when ‘staff turnover’ costs (redundancy and recruitment costs) are higher. There may be some employers who are able to save money overall by using the JSS to retain workers on their books, avoiding the costs of redundancy payments today and recruitment costs tomorrow. The government’s theory is that this will make the JSS scheme viable for businesses which rely on workers whose skillsets are in short supply, for example in sub-sectors of manufacturing and transportation. But for many, the economics simply won’t stack up.

In order to understand just how many jobs these dynamics might affect, NEF first makes an estimate of the number of jobs that were likely to be at risk as of September. Based on analysis of business turnover and national unemployment data, we find that around 2.7 million jobs were at risk of being lost as of the final weeks of summer. If economic activity were to pick up through the autumn these figures could come down. But given the national reintroduction of the ‘rule of six’, and the scale and severity of local lockdowns, 2.7 million could even be an underestimate of the true number of jobs currently at risk.

Next we need to know whether employers are likely to keep workers on using the JSS. To get a sense of this, we adapt the Resolution Foundation’s worker ‘archetypes’ approach to modelling the JSS (comparing the cost of retaining multiple workers part-time on the JSS against the cost of retaining one worker full-time on a given salary) by adding into the equation an estimate of the financial benefits of employee retention (the avoided costs of redundancies and rehiring workers). To do this, we use estimates for the observed relationship between ‘employee turnover’ and firm financial performance.

What really matters here, however, is not what actually happens over the winter, but rather what employers currently perceive will happen to the UK economy over the coming months. If employers believe their turnover is likely to pick up later in the winter, then avoiding the costs of having to rehire later is more attractive. Firms will be more likely to pay an employer contribution towards unpaid hours on the JSS, and less likely to make redundancies now. However, if firms are pessimistic about future turnover, then they may as well make workers redundant now rather than later and the JSS will make little financial sense.

In order to model the likely effects of the JSS for at-risk jobs while taking account of these sensitivities to employer optimism about the future economy, we construct three illustrative scenarios. However, the level of firm optimism doesn’t just affect the proportion of at-risk workers who might receive support through JSS, it also affects the numbers at risk in the first place. This is because more pessimistic expectations mean employers will see less benefit to retaining staff on their books. For each of our scenarios, we therefore adjust the initial estimate of 2.7 million jobs at risk up or down, depending on the level of firm optimism.

- Downside scenario: Employers expect some economic recession to take place over Oct-Dec 2020, with the economy shrinking by around 3.65% (approximately half of the decline seen in March 2020 when the first lockdown was enforced). Under this scenario, the ‘at-risk’ group is 3.3 million people.

- Upside scenario: Employers expect strong growth (4.4%) by Oct-Dec 2020. This is our best case, based on the median of a panel of independent forecasts made in September, made prior to the tightening of social distancing regulation. The ‘at-risk’ group is 1.9 million people.

- Core scenario: Employers expect very limited growth (0.1% of GDP) by Oct-Dec 2020. This is our central estimate, and the growth estimate is based on the OECD’s ‘double hit’ scenario for the UK. The ‘at-risk’ group is 2.7 million people.

Figure 1 below sets out the proportion – and total number – of at-risk jobs where the incentives of the JSS are unlikely to be sufficient for employers to retain workers on the JSS. In our most optimistic scenario, the JSS would not be able to avoid 900,000 job losses, in our most pessimistic scenario the number is 2.9 million.

Figure 1. NEF modelling suggests the poor cost-benefit profile of the current JSS means that employers are only likely to save a small fraction of jobs.

It is hard to know for sure where employer optimism is likely to be right now, as firms start to make their redundancy decisions in view of the JRS ending this month. However the OECD’s double hit scenario represents a reasonable core scenario given that we now know the virus is already resurging in the UK, and local lockdowns are being extended. Our core scenario, which uses the OECD’s forecast, suggests that 83% of jobs at risk of redundancy going into the autumn, a total of 2.2 million jobs, out of 2.7 million at risk, are unlikely to be protected by the JSS.

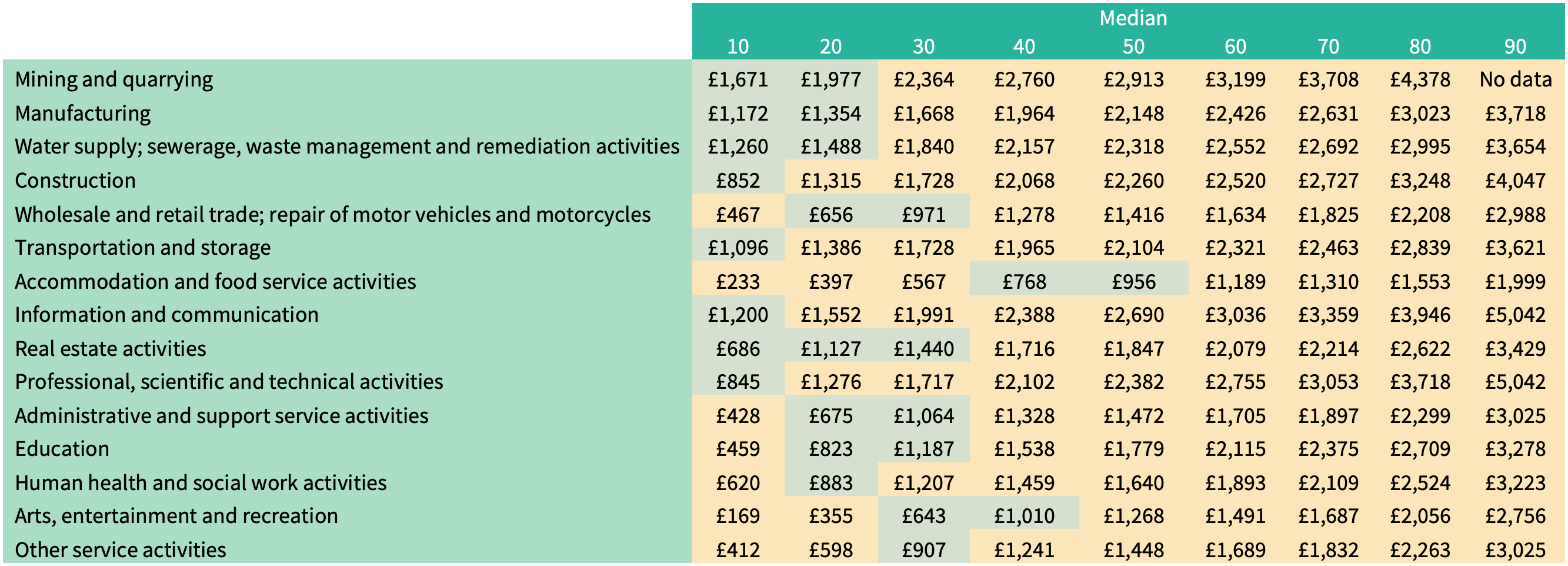

Our analysis also breaks this number down by sector and level of income. Table 1 below shows how the incentives of the JSS are likely to play out across sectors and across earnings levels, assuming our core scenario for firm optimism. Each cell in the table represents workers at a given income percentile within a sector. Green cells indicate that on average the economic incentives of the JSS mean firms are better off keeping two workers on at 50% hours through the scheme. Yellow cells indicate where a firm would be better off keeping one worker on and making the second job redundant. The key controlling factor which prevents many low-wage workers being cost-effective on the scheme is the minimum salary threshold at which the employer can claim the £1,000 Job Retention Bonus (£520 per month). The key controlling factor at the high-wage end of the spectrum is the cost of the employee’s salary in proportion to the size of the Job Retention Bonus. Some variation between sectors in the ‘window of cost-effectiveness’ can be seen – this is primarily caused by variation in rehiring costs between sectors.

Table 1. NEF modelling highlights the ‘window of cost-effectiveness’ implicit in the JSS scheme which varies by sector. Workers at both the top and bottom ends of the income spectrum are unlikely to be viable on the scheme.

Sectoral income distribution estimates (percentiles). Green cells highlight salary levels at which it is cost-effective to maintain two workers at 50% hours on the JSS instead of maintaining one worker at 100% of hours and making one redundant. Estimates relate to NEF’s ‘core’ scenario of firm optimism.

Source: NEF analysis of Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ONS), Business Impacts of Coronavirus (ONS), and HM Treasury guidelines on the JSS scheme.

These varying dynamics across sectors mean that the JSS is likely to provide a varied level of support across the economy as well. Figure 2 shows the number and proportion of jobs that the JSS is likely to support across industries. The analysis shows that job losses are likely to be concentrated in sectors like accommodation and food services, admin, education, and retail. When considered in proportion to the size of a sector, job losses are also very significant in the arts and entertainment sector.

Figure 2. NEF modelling suggests there could be up to 2.2 million unsupported jobs under our core scenario, this is how they might be distributed by sector.

But things needn’t be this way. The key feature that makes the JSS so limited in terms of job protection is the size of the employer contribution for unworked hours. Figure 3 below shows how simply adjusting this contribution down from the current 33% – for example to 25% or 10% respectively – would likely see 400,000 to 1.4 million more jobs protected by the scheme.

Figure 3. NEF modelling highlights that relatively modest increases to the government’s contribution towards unworked hours on the JSS could significantly increase the proportion of at-risk jobs which are supported.

Based on this analysis, there is a very strong case for improving the JSS. The cost of reducing the employer’s contribution to 25% of unworked hours is estimated to be around £65 per worker per month, and the cost of reducing it to 10% comes in at around £200 per worker per month. The latter would convert the JSS from a scheme which is likely to support only a minority of jobs, to one which could support the large majority. The upfront costs of such a scheme would bring it closer in line with the costs of furlough in October. But as modelling by the National Institute for Economic and Social Research has shown, due to higher taxes and reduced social security payments, subsidising wages in order to protect jobs is likely to pay for itself in the longer term.

Photo by Jose Fontano on Unsplash

Campaigns Coronavirus response Living income

Topics Work & pay