Basic human needs: what are they?

18 July 2014

Social justice and environmental sustainability are twin goals of NEF’s work on a new social settlement, which explores the future of Britain’s welfare system in the face of rising inequality, accelerating climate change and a dysfunctional economy.

Drawing inspiration from the Brundtland Report on sustainable development, we are aiming for a settlement that can meet ‘the needs of present generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.’

But what do we mean by ‘needs’? Curiously, Brundtland doesn’t elaborate. Today we release a new working paper by Ian Gough, setting out a theory of human need.

The essential premise is that every individual, everywhere in the world, at all times present and future, has certain basic needs. These must be met in order for people to be able to pursue their own goals, to participate in society and to be aware of and reflect critically upon the conditions in which they find themselves. Why does this matter? Because understanding needs in universal terms, applied across time and place, makes it possible to plan for and measure progress towards our social and environmental goals, both globally and into the future.

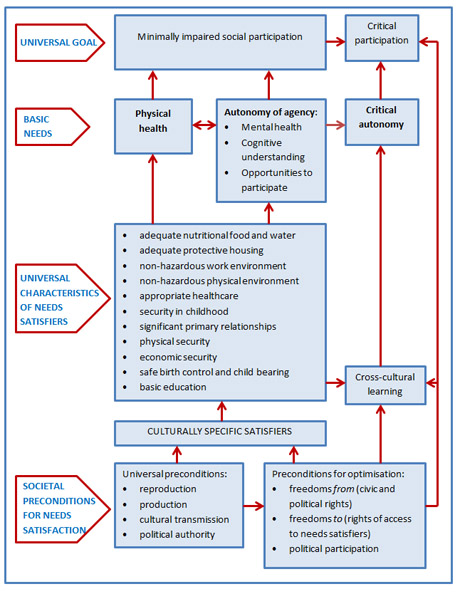

Gough defines basic needs as health, autonomy of agency and critical autonomy. Autonomy of agency means being able to take action and participate. Critical autonomy means being able to question things. Basic needs are held to be objectively verifiable and to apply in all circumstances, to everyone.

How these needs are met, on the other hand, will vary – often widely — according to the social, environmental, economic, political and cultural circumstances in which people live. In other words, basic needs are absolute, while ‘needs satisfiers’ are culturally specific or relative.

However, there are certain needs satisfiers that are generic, because they enhance physical health and human autonomy in all cultures. These are: adequate nutritional food, water and protective housing, a non-hazardous physical and work environment, appropriate healthcare, security in childhood, significant primary relationships, physical and economic security, safe birth control and child bearing, and basic education. There are also preconditions for satisfying needs. Some of these apply in all circumstances and some are necessary for satisfying needs in optimal ways. The table below shows how goals, needs, satisfiers and pre-conditions relate to each other.

The paper argues that need theory offers a more useful tool for planning and measuring progress than theories based on wants and preferences, which prevail in classical economics. Wants and preferences are eternally relative and adaptable. They are changeable and ultimately insatiable, so they’re entirely unhelpful when it comes to dealing with planetary boundaries. They cannot be compared across space or time – and therefore offer no help to policy-making for sustainable social justice.

There is some overlap with the capabilities approach developed by Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum, but only need theory offers objective, evidence-based and philosophically grounded criteria for making decisions about how to allocate resources. It provides a basis for understanding what future generations will need and what will make it possible for those needs to be met. It suggests a moral framework for deciding about trade-offs. And it strongly indicates that today’s surplus preferences cannot be allowed to impair the health, autonomy and critical capacity of present or future generations.

The theory of need in outline

Image credit: pedrosimoes7 via Flickr

Topics Climate change Health & social care Inequality Public services Wellbeing