Cold truths about our cold homes

We can’t continue with this annual ritual of concern – Government needs to take action

08 February 2018

It’s difficult to properly grasp the human cost of cold homes. Whether it’s down to the dispassionate language of ‘excess winter mortality’, or the hidden way that cold temperatures lead to circulatory and respiratory problems, it’s not an issue treated with the seriousness it deserves. Perhaps it’s the fact that the problem is most severe for the elderly, who are often neglected in policy and in broader society. Yet every winter we read the same headlines about the 9,000 or so early deaths (four times the toll of motor fatalities), as well as the significant psychological impacts that come from living in a cold home.

The problem of cold homes comes down to three interrelated parts: household income, the cost of fuel, and the energy-efficiency of the building. All three deserve our attention. Compared to our European neighbours, UK household income is fairly high, but unequally distributed. Fuel prices, perhaps surprisingly, are lower than almost anywhere in Europe. Fuel bills, on the other hand, are not, and the answer to this riddle shouldn’t come as a surprise: it’s our housing.

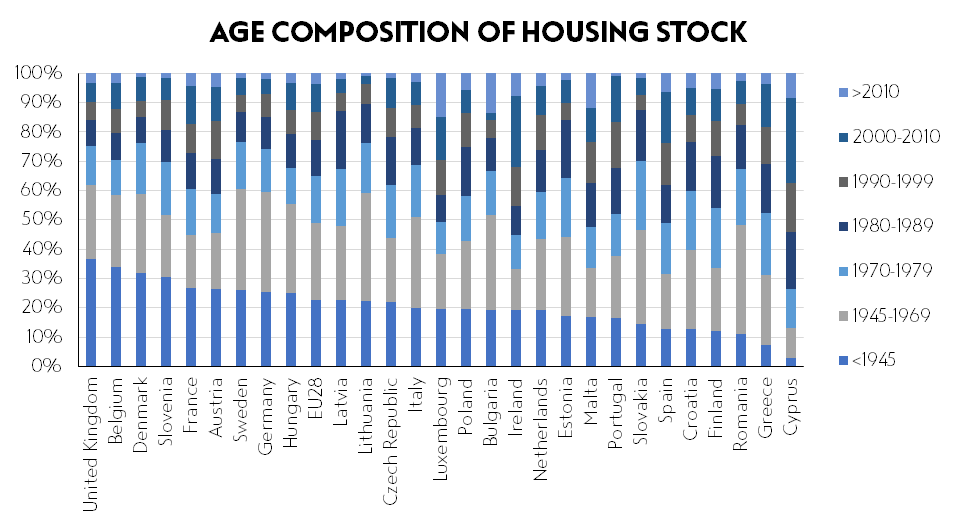

Yes, once again the UK’s failure to ambitiously build and renovate rears its ugly head. Over a third of the homes in the UK were built before 1945 and three quarters before 1980. This puts the UK at the top the rankings for the oldest building stock in Europe. Often these older homes are single dwellings with poor insulation and heating systems that consume four times as much energy. Not only have our European neighbours updated their building stock, many countries in the north use more efficient and less polluting electric or district heating.

Source: European Commission: EU Buildings Database

But there is potential for the UK to chart its own course on housing. For years now, the housing conversation has felt like a live auction for votes, with each political party’s manifesto promising ever more ambitious house-building programmes. And that’s fine, if the reality matches the rhetoric; but we also need to be thinking about the type of developments that we’re planning on building.

NEF has developed proposals to correct the country’s artificially inflated land prices, and ensure that public land is used to provide housing that is both genuinely affordable and developed in response to the needs of the local community. And one of these needs is for energy efficient homes – not only for health of people, but for the planet too. The Committee on Climate Change has put buildings’ energy efficiency as a central plank in its strategies for the UK to meet its climate targets. There have been calls to make energy efficiency part of the National Infrastructure Plan to unlock the levels of public investment that required to renovate the existing building stock.

The cold snap this week will eventually pass, but we can’t continue with the annual ritual of concern for the cost to human life and wellbeing caused by under-heated homes. Our current approach to housing is great at increasing land value, but poor at delivering homes that are affordable, community-led, healthy, and sustainable. An ambitious housing strategy would offer the chance to tackle these entangled issues together.

Topics Climate change Housing & land