Public land is a feminist issue

Community housing groups across London are putting women and non-binary people at the forefront of their plans for building affordable housing

10 August 2018

When the Landless People’s Movement of Brazil won back the land they had occupied, the women in the movement insisted that houses be built to form a single compound. This way, they could continue to communalise washing and cooking and give each other support when abused by men. This is just one story in a long history connecting socialist feminism to the politics of the commons.

Across the UK in the past few years, this radical history has continued as community groups led by women have sprung up to take control of housing in their local area. They are rethinking the way that gender inequalities are built into the physical structure of homes and cities.

The driving force behind this movement is the need for more genuinely affordable homes. The StART Haringey campaign was prompted by anger over outline planning permission for just 14% affordable homes when the former hospital site of St Ann’s was advertised to private developers. Reclaim Holloway activists were similarly concerned that private developers would prioritise luxury flats on the Holloway prison site while there are 20,000 families on the waiting list for social housing in Islington.

They are right to be concerned. Our recent report has shown that only one in five new homes built on public land will be affordable.

But there is a lesser known aspect to this story, which is that the lack of affordable or social housing disproportionately disadvantages women, particularly women of colour.

The gender pay gap means that women spend a higher proportion of earnings on rent and have more difficulty saving for a deposit. The bedroom tax affects twice as many women as men because of its implications for single parents (who are more likely to be women). Homeless women don’t get the gender-specific services they need. And housing benefit changes have made it harder to support women who flee domestic violence.

Community-led housing can address these gender inequalities, not only by building new homes but by changing the way we build them.

Preventing domestic abuse

For thousands of women and children across the country, their home is the most dangerous place they can be. Last May, eight activists from Sisters Uncut broke into and occupied the former Holloway Prison visitors centre to demand that after redevelopment it be used as a women’s building for local families and domestic violence survivors.

Reports from charities like Solace Women’s Aid show that soaring rents and a shortage of housing stock is having a devastating impact on vulnerable families, forcing women and children to stay in dangerous situations for prolonged periods. Last year, over 60% of women entering refuges from a secure social housing tenancy lost it when they moved.

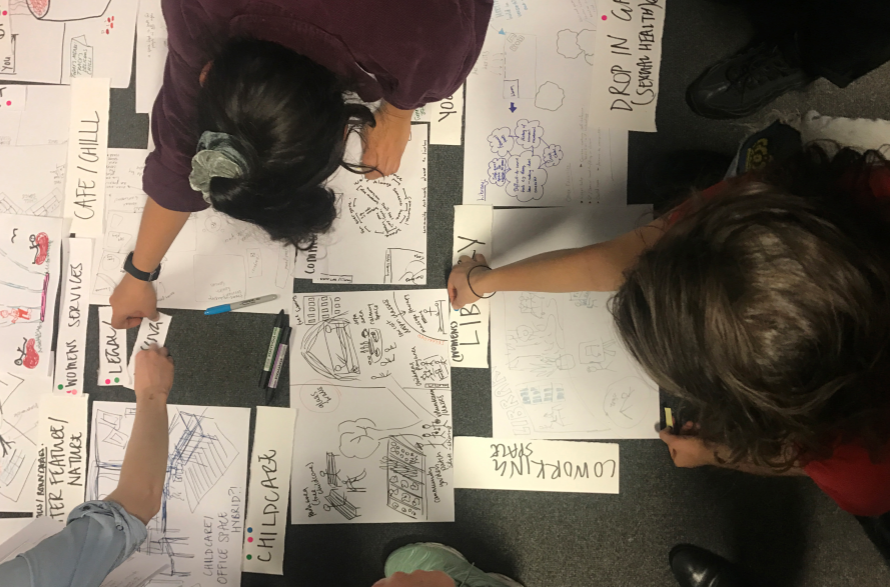

At a Sisters Uncut workshop last year run by architect Esha Thapur, activists and Islington residents shared ideas for the women’s building, ranging from a space for art therapy to shelter for the homeless in the winter. We also discussed the role of communal spaces as a form of resistance to domestic abuse. Helen Hester highlights how intimate partner violence flourishes in sites of isolation as victims are more easily manipulated, and detached from their support networks.

When it comes to public space, girls feel 10 times more unsafe than their male counterparts, and one in five LGBT people report not feeling safe in their local area. As StART Haringey — who are now working with City Hall to develop the site — develop plans for green public spaces on the St Ann’s site, they are focusing on how the presence of facilities such as public toilets or adequate outdoor lighting shape accessibility.

Reorganising housework

The restructuring of housing and public space into more communal arrangements is not just a question of power and safety but also work. Unpaid domestic work such as cooking and cleaning means that women work longer hours than men for much less money in isolating conditions.

Dolores Hayden’s Grand Domestic Revolution looks at feminist building projects, from communal kitchens in the 19th century to overcome isolation, to house designs in the 1930s with rounded rooms to minimise time spent sweeping.

Today, the single family home is still labour intensive and energy inefficient. Helen Hester asks us to consider, “how many people in London cook individual dinners every single night using individual supermarket ingredients? How many cookers are on at 6pm?”

StART Haringey, Reclam Holloway and the Rural Urban Synthesis Society (RUSS) have therefore explored plans for communal kitchens and laundries. But community-led developments on public land could also offer high quality, communally accessible workshops, health facilities, media suites, labs, food growing and maker spaces.

Collective care

How can these projects also ensure that elderly and disabled people are integrated into the community? StART Haringey has proposed that 7% of homes on the site could be sheltered or supported housing.

The prevailing approach of warehousing older people into low density bungalows at the edge of towns increases loneliness and assumes a privatised model of care provision. At a recent StART meeting, architecture student Ricardo explained how co-housing offers a strategy for adults to share caregiving in reciprocal relationships among an extensive group of people. In the face of today’s for-profit childcare and elder care providers, a vision of care that returns to this model is urgently needed.

NEF is currently in the process of establishing the UK’s first childcare co-operative for low-income families in Vanguard Estate, Lewisham. A similar project has been discussed as one potential use for the old visitors building on the site in Holloway. The lack of flexible, affordable childcare in London entrenches inequalities (with 31% of low-income families burdened with debt from childcare) and creates major barriers to female participation in the labour market. Projects like this could start to tackle these problems.

However, as activist researchers Helen Hester and Joni Cohen have highlighted, we should expand thisconversation to think about the needs of many different kinds of caregiver. In the absence of state support, queer and trans people (frequently led by people of colour) have had to establish their own communities of care without wider infrastructures of support in the face of employment discrimination, threats of gendered violence and increased vulnerability to homelessness.

As women occupy just 10% of the highest ranking roles in architecture, it is no surprise that cities are still built by men, for men. If we want to offer spatial solutions to social problems we need to ensure that campaigning groups are inclusive and representative of vulnerable groups in the wider community. StART Haringey’s emphasis on non-hierarchical consensus decision making does just this — rejecting patriarchal, top-down organising models to bring a feminist ethos into the public land debate.

Campaigns Save public land

Topics Housing & land