Climate finance: our planet is too big to fail

Do we need a climate bailout?

29 November 2018

10 years on from the groundbreaking Climate Change Act, we take this week to investigate what preventing climate chaos will look like across the UK economy. From digital tech to the health system, governance to finance, and how to talk about climate change, we explore where we are falling short — and how we can change the rules to build an economy fit for the future.

A decade has passed since the UK ratified a law the likes of which the world had never seen: the 2008 Climate Change Act. It’s also been a decade since the collapse of Lehman Brothers, leading to the global financial crisis, and a bailout of the banking system.

10 years on, alarm bells are beginning to ring. There is a growing realisation that climate breakdown could wipe out trillions of pounds worth of assets, making the devastation of the 2008 financial crisis seem like a walk in the park.

Our economy is inextricably bound up with the state of our planet, which is — of course — ‘too big to fail’. If we are to preserve any semblance of a functioning economy, this time round we may need a ‘climate bailout’.

A financial challenge or a political one?

Sadly climate change is hardly ever on the radar of the political establishment. Just weeks after the IPCC called for a 50% cut in CO2 emissions within the next 12 years, climate change was not even mentioned in the Chancellor’s Budget speech. The economic impacts of runaway climate change — on trade, natural resources, and entire industries — are continually ignored in announcements like these, in favour of a national obsession with ‘the deficit’.

This obsession stems from the Cameron-Osborne era, which saw the mainstreaming of the idea that the government needs to live within its means, ‘like a household’. But the ‘household analogy’ is a myth: the government is not financially constrained like a household is. Government spending is needed for investment in green infrastructure projects and to help create greener jobs, higher wages, and greater revenue across the country. We need to do away with the ‘household analogy’ myth if we hope to transition to a low-carbon economy.

The total global infrastructure investment required for a successful low-carbon transition until 2030 is estimated to be around the $95 trillion mark. That means investment would have to more than double from $3 trillion to just under $7 trillion every year (see graph below for breakdown of requirements).

The green finance gap: estimated green investment requirements per year, 2015 – 2030

We will also simultaneously need an unprecedented scaling down of carbon-intensive finance. A recent study put worldwide fossil fuel subsidies at $5.3 trillion in 2015 (6.5% of global GDP). Another study suggests that by reducing taxes and increasing subsidies to oil and gas production, the UK is the only G7 country that has sharply increased its fossil fuel support in recent years.

The scaling down of fossil fuel subsidies, and ramping up of green investment undoubtedly can — and must — be done. The question is not about financial resources, but rather about political will.

Whatever it takes to preserve… a healthy planet

In 2012, President of the European Central Bank Mario Draghi infamously stated he was prepared to do “whatever it takes to preserve the Euro”. If only our policy makers took a similar approach to the fight against climate change.

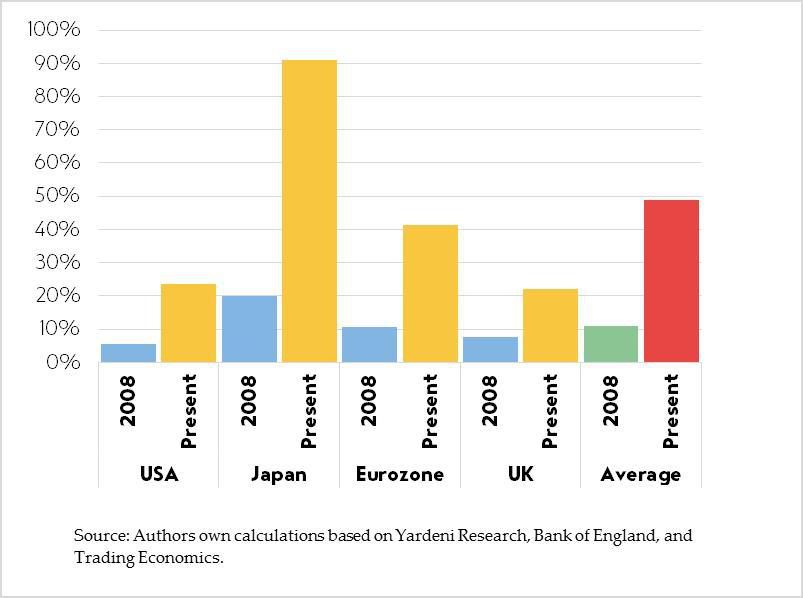

Following the path of the world’s leading central banks, Draghi went on to pump €2 trillion of newly created money into financial markets. To date, the world’s major central banks have expanded the size of their balance sheet at a rate not seen since World War II (see graph below). They have created over $15 trillion of new money through their quantitative easing (QE) programmes, pouring this money into the financial sector the name of ‘maintaining price stability’.

Balance sheet size for major central banks, 2008-present

But the truth is that these QE programmes were launched as backdoor bailouts of a defunct global financial system. Indeed, a main intention of QE is to prop-up asset prices in financial markets (like stocks and bonds) with the hope that some investment will trickle down into the real economy.

In reality, investors reacting to QE have channelled their investments into pre-existing financial and property assets. This has inflated the price of assets, and enriches their owners, with minimal positive impact on the real economy. Where investment has been channelled into the real economy, there is good reason to believe that this has gone into fossil fuel and carbon intensive sectors.

Five ways to reshape finance for a sustainable economy

If we want to get a serious jump on the fight against climate change we need to ensure all economic and financial levers are being pulled in the right way.

Better cooperation between monetary and fiscal authorities, coupled with fiscal rules that are fit for purpose, will allow the state to pool some of the risk that markets are unwilling take on their own (especially in face of growing uncertainty). It will enable the state to play a more active role in shaping markets and co-creating a financial system that promotes long-term green investment.

Here are five ways to do that.

1. Strategic QE for the climate crisis

When central banks unleash QE, they should get smart about it, acting more strategically and redirecting the newly created money towards a green transition. For example, we could use the newly created money to finance a public investment bank that could invest in green infrastructure projects or lend to green businesses.

2. Green the fiscal rules

The public finances in the UK are run according to a set of ‘fiscal rules’: inflexible limits for public debt and borrowing. These are pretty useless for helping us react to the need for long-term, large scale public borrowing.

Colossal monetary stimulus programmes have opened up significant ‘fiscal space’ for Treasuries, resulting in record low borrowing costs for governments. Yet finance ministers have not taken anywhere near enough advantage of the fiscal potential the central banks afford them.

Countering climate change requires sustainable, long-term investment solutions and a complete re-think of fiscal rules and public finance.The rationale and framework behind fiscal rules must be recast to realise the full potential of public balance sheets. Most importantly, front and centre of the fiscal rules framework needs to be the ‘environment’ and the task of realising a just green transition.

3. End fossil fuel subsidies

While we almost certainly need better carbon taxes to correct the vast implicit subsidy given to polluters — for whose environmental damage we all ultimately pay — the more immediate task is to begin weaning ourselves off of fossil fuel subsidies and our economic dependence on carbon intensive sectors. It is essential to take into account the risks to communities which are dependent on fossil fuel jobs: any transition away from fossil fuels must be collaborative, and provide high-quality jobs to replace those lost.

4. Green credit guidance

Our overly concentrated banking sector prioritises short-term profits over the environment. With banks benefiting from guarantees and implicit subsidies from the government, policy makers could implement green credit guidance that ensures banks allocate more credit towards sustainable activities and less credit for carbon intensive sectors.

5. Break up RBS into an army of green local banks

The government should also turn RBS into a network of 130 local banks, but with a climate twist: an environmental emphasis hammered into their social mission to serve their local area. Alternatively, RBS could be forced to pioneer new forms of green lending and offer patient strategic finance for urgent adaptation and mitigation activities.

Bailing out our planet is completely feasible. Over the next ten years of climate action, need to get real about the role of monetary and fiscal policy. The question is whether policy-makers will come to understand — with the same urgency with which they bailed out the banks — that our planet is simply too big to fail.