Setting a dangerous precedent

What can finance teach us about the risks of deregulation?

14 March 2019

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis and the devastation left in its wake is a textbook illustration of the catastrophic effects of deregulation. It is a testament to what happens when the rules and regulations designed to serve and protect society are stripped away, replaced by a supposedly ‘self-regulating market’ benignly guided by the profit-maximising ‘free-hand’.

Much like the Better Regulation agenda – the big business-backed EU push to strip back regulations on anything from pharmaceuticals to food – proponents of financial deregulation promised greater profits, which would lead to the efficient allocation of resources, more employment, and higher levels of growth. Instead, a privileged few managed to scoop up the gains of deregulation, while the devastating and overwhelming losses have been pushed onto the rest of society.

Regulation and finance: the ‘golden age’ of capitalism

In the aftermath of the second world war, European policymakers were acutely aware of the financial system’s historical tendency to swing from boom to bust, and regulated the banking and financial sectors accordingly.

Alongside the establishment of the Bretton Woods institutions, regulators had a number of policy tools at their disposal to protect society from unrestrained speculation and casino-like gambling – of the kind witnessed in the run up to 2008. Sensible rules were also in place to curb excessive risk taking in the real estate sector, and housing bubbles were successfully thwarted. In fact, our research suggests that effective regulation was also used to ensure that banking activities supported broader social, national and industrial objectives, proving pivotal to the post-war economic boom which has been called ‘Europe’s golden age of capitalism’ (1945 – 1975).

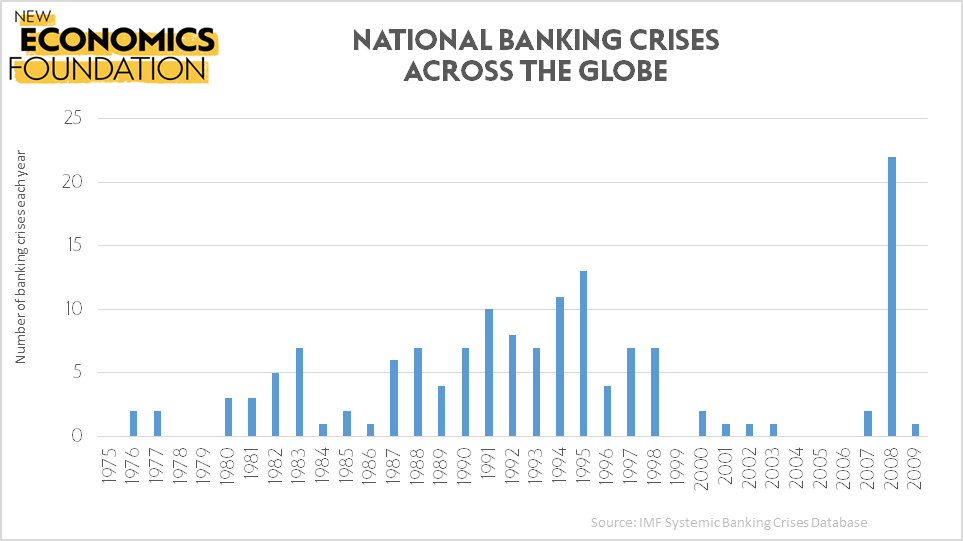

According to academics Monnet and Kelber, during this time Europe did not experience a single banking crisis. Yet from 1975 we’ve seen the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, and the wider drive to deregulate finance – using logic that has continued in the form of the EU’s so-called ‘Better Regulation’ agenda. Since then, we’ve seen 147 national banking crises across the globe, with roughly one third taking place in Europe.

‘Freeing up growth’ in the 70s and 80s

Much like the Better Regulation agenda, the theoretical support for financial deregulation is a central plank of neoliberalism. According to this logic, financial markets need to be left to their own devices to operate properly. From the 1970s onwards, financial regulation was largely perceived by policymakers, regulators, and mainstream academics as standing in the way of jobs and economic growth.

Lord Adair Turner, the former chairman of the UK Financial Services Authority, has said that market deregulation became so popular and dominant that it was like a religion.

Over the course of the 1980s, the regulations that had served Europe so well throughout the post-war boom were stripped back, and democratic oversight over them removed – only to be replaced with ‘self-regulating’ regimes with light touch technocratic scrutiny.

Deregulation in practice

From 1988, under the newly established Basel Capital Accords, which governed financial stability, European banks were permitted to internally model their own financial and lending risks instead of adhering to statutory regulation. While banks were still supposed to retain a certain amount of shareholder investment as a buffer in case loans went bad (a regulation known as ‘capital requirements’) the internal models developed by Europe’s biggest banks allowed them to keep their reserves artificially low so that they could profit more (more information on banks and buffers here and here).

This ‘self-regulation’ is nothing short of letting students mark their own homework – with predictably dire consequences when banks game the system. To make matters worse, in 2001 a new set of reforms (known as the Lamfalussy Process) was adopted to change the underlying decision-making process for financial regulation.

In a nutshell, the Lamfalussy Process aimed to make financial regulation less time consuming for policymakers, by leaving certain details to civil servants. But the end result was that important democratic oversight over the financial sector was handed from the European Parliament to unelected technocrats who, most importantly, where encouraged by a colossal financial lobby. These reforms were considered a good pilot for the EU’s Better Regulation agenda, some years later. Alter-EU says that:

“Instead of new rules being subject to scrutiny by the European Parliament and Council, the process relies on sector-specific committees, regulators and member-state representatives to shape them. In the Lamfalussy process technocracy has replaced democracy.”

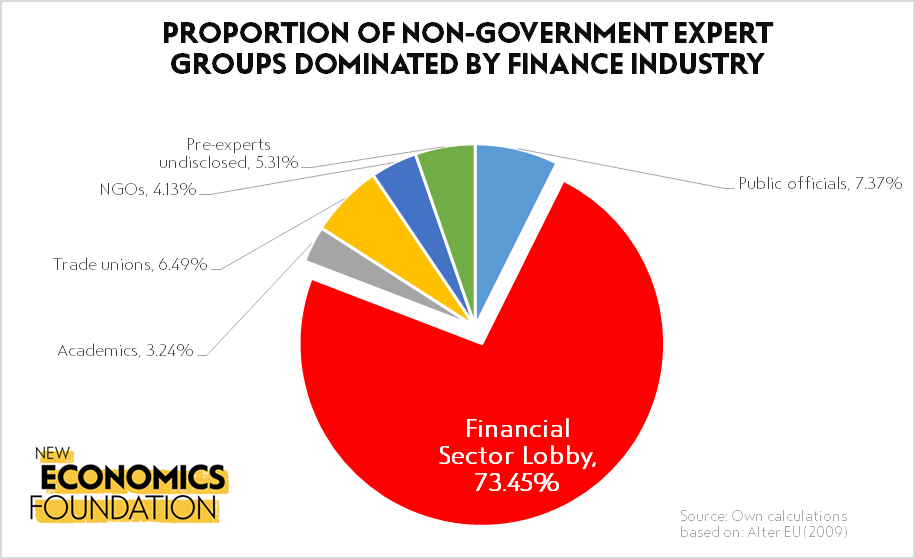

As a result, in the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis the European Commission’s Directorate General for the Internal Market, which is responsible for drafting proposals for financial regulation, shaped policy with the counsel of external stakeholders known as ‘expert groups’. A brief review of these expert groups shows that they were dominated by representatives of private financial corporations.

Three out of four of the representatives in these expert groups were from the financial sector; with only one in 25 coming from NGOs. 229 corporate financial experts participated, vastly outnumbering the 150 Internal Market policymaking staff responsible for drafting legislation.

In addition to these expert groups, a report by Corporate Europe Observatory showed that the financial industry spent more than €120 million a year on lobbying in Brussels and employed more than 1,700 lobbyists to influence EU policymaking. This corporate lobbying and stakeholder engagement prioritising corporate interests fundamentally skews the legislative process – and is a recurring theme in the Better Regulation agenda.

And the financial sector’s big investment in corporate lobbying is paying off. Evidence suggests that the dispensation of financial regulations from the 1970s onwards dramatically increased the profits of the financial sector compared to the post-war period. When measured as returns on equity (shareholder investment), average profits for the EU banking sector reached colossal heights in the run-up to 2008 – at times nearly reaching 25% (much higher than in the post-war period).

Despite soaring profits, our recent research suggests that the deregulatory policies of the 1970s and 80s led to a lower share of bank lending to businesses – lending that results in real world job creation and higher incomes. Instead, there has been seismic growth in non-productive and speculative lending, in particular real estate and financial trading, as well as environmentally damaging activities. If anything, deregulation has helped to swing the economy from the post-war boom to bust.

A light touch self-regulating financial system was supposed to allocate resources more efficiently, deliver more jobs, and increase growth. While deregulating the financial system may have increased the profits of the financial sector, it came at the hefty price of a global financial crisis.

Advocates of the EU’s Better Regulation agenda should have learned that overzealous deregulation in the name of short-term profits can endanger the long-term stability and safety of our society. The deregulation of the financial sector is perhaps the most painfully obvious example of the dangers of deregulation to date. Learning from it means being wary of any plans to strip back regulations in favour of the ‘self-regulating’ market.

The rules designed protect us and the places and habitats we hold dear have been painted as‘burdens’ on business – but a successful economy is one that puts people and planet first. Find out more about NEF’s work to end the deregulation agenda here

Image: Pixabay on Pexels

Campaigns Halt EU deregulation

Topics Banking & finance