A safety net for all

The Minimum Income Guarantee would make sure no one falls through the gaps in our social security system.

03 April 2020

Yesterday the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) revealed that nearly one million people have applied for universal credit (UC) in the final two weeks of March – a 10-fold increase on the usual level of applications.

This enormous surge makes it clear that for many the coronavirus crisis is an economic emergency, as well as a health one. And just as some of us are more vulnerable to the virus than others, it is increasingly clear that some are more vulnerable than others to the economic shock. We need to make sure that, during this period, no one slips through our social security safety net by ensuring everyone has access to enough cash to meet the basic cost of living. And we need to do it immediately.

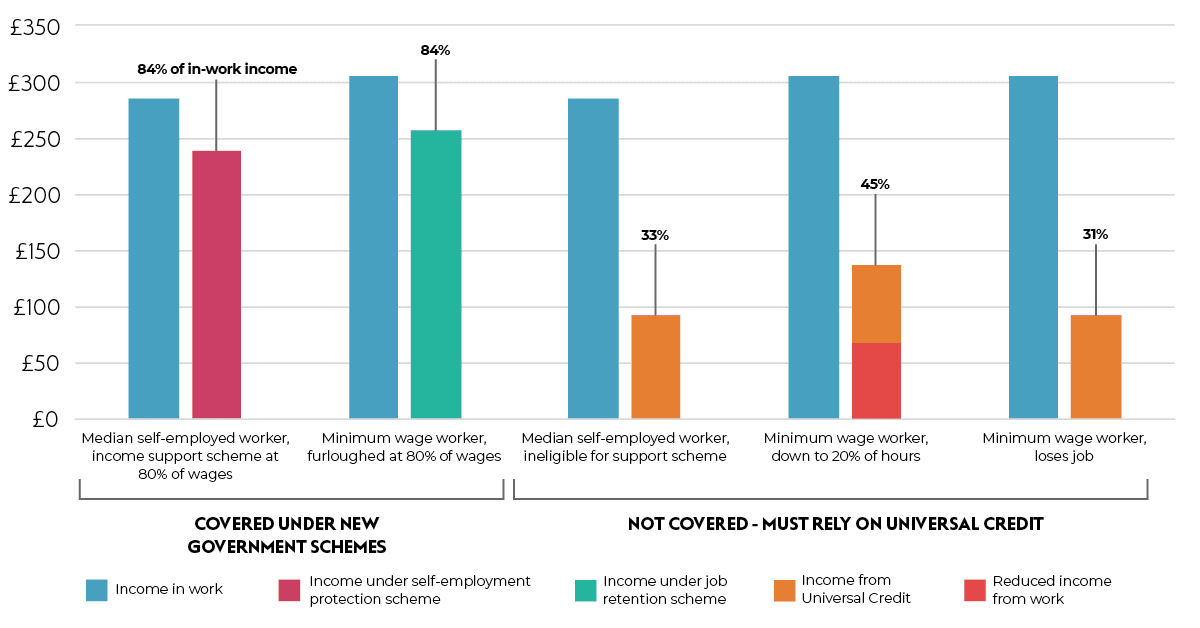

The government’s job retention and self-employed income protection schemes ensure 80% of incomes for many people, but still exclude large numbers of workers. These include employees who are losing their jobs, employees who have taken on a new job after 28 February 2020, and self-employed people who have been operating for less than a year, amongst others.

This is creating a clear divide between those who are protected under the government’s schemes, and those who aren’t. The former will have nearly their full wages covered by the state.

But those who aren’t will have to rely on our decimated social security system. On the eve of the current crisis, the UK’s safety net was particularly weak — both among advanced economies globally and compared to the UK’s own post-war history. And although the government has temporarily increased the main elements of universal credit and tax credit payments by £20 a week, overall this represents a reversal of just one fifth of the cuts to welfare since 2010. Meanwhile, those on other so-called ‘legacy benefits’ (such as jobseekers allowance and employment support allowance) and who have not yet moved over to UC have not seen any increase at all.

The additional £20 only brings the main adult payment up to around £90 a week. Hundreds of thousands of new claimants are now coming to realise what those who have relied on this system over past years have known for a long time: it is simply not enough to cover living costs for the majority of people, even with the modest top-ups for housing and costs for children. And the income shock — the change in income after moving onto UC — can cause particular economic pain. Someone may be able to survive on lower resources if they have time to plan, but an unplanned change without the ability to adjust their outgoings — such as rent, mortgages or other debts — can be ruinous.

Graph 1 below illustrates the gaps in the government’s current response for families, with respect to these possible income shocks. It shows how those on either the job retention scheme or the self-employed income protection scheme will still keep over 80% of their weekly pay after tax, compared to what they would have earned at work. (The figure is more than 80% due to slightly lower effective tax rates at a lower gross income.)

But those who must rely on the social security system will lose out significantly. The average self-employed worker not eligible for the above scheme will only get 33% of their income, a loss of almost £200 a week. An adult working full time and earning the minimum wage — the most meagre of in-work incomes — will only get 31% of their previous income once on UC, a loss of over £210 per week. And if instead that minimum wage worker had their hours cut down to working one day a week, they will still have less than half the income they would have had in work even with the modest UC top up available to them.

Graph 1: Under the current system, those not eligible for the job and pay protection schemes must rely on inadequate social security

Weekly net in-work income compared with income after a loss of work for a single adult homeowner over 25 with no children, under new government schemes

Note: 80% of gross income is retained for those on government schemes amounting to over 80% of net income due to lower average tax rates at lower incomes

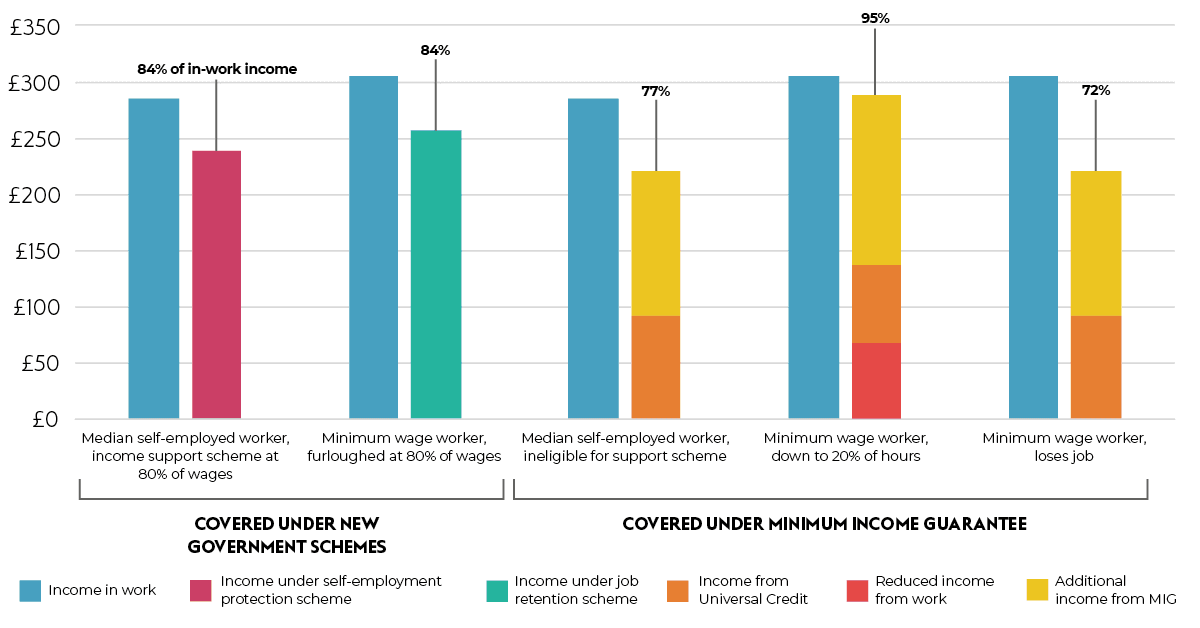

We urgently need to ensure that no one slips through the net. At NEF, we are proposing a Minimum Income Guarantee (MIG) as an urgent part of a range of measures to ensure that everyone has enough to cover the basics such as rent, bills and food.

The MIG would provide an income floor for all working age adults for an initial three months, with the option to extend. It is comprehensive, non-conditional, and non-means tested at the point of access. Not only does this avoid the stigma of claiming, but it also eases the process.

We argue that the MIG should be set at a rate of £221 per person per week, equal to the 2019 minimum income standard, established by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and the Centre for Research in Social Policy, excluding rent, mortgage and childcare costs (forthcoming work at NEF will set out proposals for alleviating these costs separately).

Those already on benefits would get an automatic top-up to bring the main element in the relevant benefit up to the level of £221 per person. For new applicants to UC, payments will be non-conditional and non-means tested at the point of access, by using the universal credit advanced payment system — crucially this means no five week wait for payments.

Anyone can apply for the MIG. But where the MIG takes an individual’s disposable income above £2,500 per month, the difference above £2,500 would need to be paid back — either through any backdated payments made through other government schemes, or through higher taxes in the 2021/22 tax year. Universally raising the level of the safety net will ensure that those losing all or part of their income will not be expected to fall so far, and will also raise income for current claimants, who may face further hardship as a result of the crisis.

Graph 2 below shows how the introduction of the MIG would bring those left out of the existing schemes — and currently making UC claims in droves — onto a comparative level of support. A typical single adult losing their job will now have an additional £127 per week in their pockets to pay for the basics compared to the current offer under universal credit.

And the system can top up those who are working on reduced hours — the example we give shows how a minimum wage worker who is reduced to working one day per week will have nearly the same level of income compared with if they were still working full time.

Graph 2: With a Minimum Income Guarantee, those not covered under the job retention scheme or self employed income protection scheme will be much better off

Weekly net in-work income compared with income after a loss of work for a single adult homeowner over 25 with no children, under new government schemes plus NEF’s Minimum Income Guarantee

Notes: 80% of gross income is retained for those on government schemes amounting to over 80% of net income due to lower average tax rates at lower incomes

The Minimum Income Guarantee is a weekly cash payment available to anyone who applies for it to the value of £221. Additional income under MIG shows how much this payment is worth additional to the amount they would have received under the current system of Universal Credit.

It is natural to ask how much this will all cost. The MIG will be in place for an initial three months with an option to extend for a further three months on a rolling basis. Outside of any payments recouped – either through the job retention scheme, the self-employed income support scheme or additional tax in 2021/22 – the MIG will be funded by government borrowing.

Initial modelling by NEF shows that the additional cost of the MIG for existing benefit claimants would come to around £3 billion per month, or £9 billion for three months. For every additional 500,000 claimants of the MIG, the marginal cost above what they would have received from the present benefit system would be a little under £0.5 billion per month, or less than £1.5 billion for three months. The latest forecasts from the DWP for an increase in the claimant count would imply a total cost for the MIG of around £4.5 billion per month, or little under £13.5 billion for three months. However, the latest DWP forecasts are likely to prove an underestimate of the demand for a MIG: the final cost may be closer to £20 billion over three months.

In which case, the question is not whether we can afford it. Compared to existing government commitments, which already run into the tens of billions, the additional cost of the MIG is relatively low, but will help mitigate against very extreme hardship for those not currently covered by the government’s new schemes.

It is clear that the MIG, or something like it, is vital to ensure that no one is left without enough to cover their basic needs. By the time the coronavirus crisis is easing, there will be many more than one million who fall outside the schemes for salaried and self-employed workers. It is vital that they find something capable of supporting them until work is available again.

Image: Pexels

Campaigns Coronavirus response Living income

Topics Social security