Funding local government with a land value tax

Swapping business rates for land value tax can plug the local authority funding gap.

13 November 2019

By Sarah Arnold, Lukasz Krebel, Alfie Stirling

Could a land value tax replace the complex business rates system that councils currently rely on for much of their funding, and raise much needed revenue? In this blog we set out some high level options for how some of the local government funding gap could be closed by replacing business rates with a land value tax.

This year (2019/20), councils face a deficit of £19.4 billion per year in real terms compared to what they would need to provide services to today’s population at the level seen in 2009/10 (2019/20 prices). During the first half of the 2020s, up to 2024/25, this deficit is due to widen by a further £8.4 billion, as reforms to local government funding will not keep pace with need. Of this widening deficit, the majority – £5.4 billion – is attributable to social care – with an additional £3 billion needed at a minimum to ensure the gap doesn’t widen for other services beyond social care.

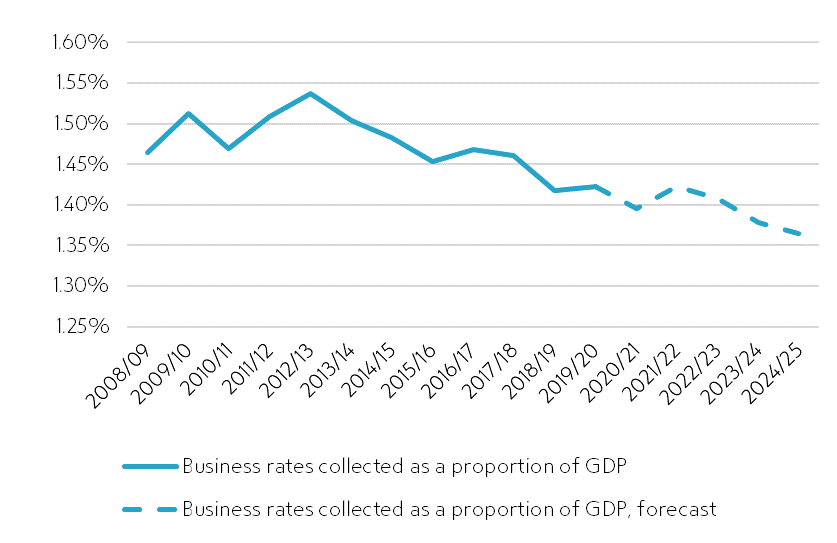

We have written elsewhere about the gaps and their causes. But in brief, in addition to rising demand, a large cause of this gap has been reforms to local finance – specifically the decision to effectively replace central government grant funding with local business rates income, redistributed through a complex formula. As the central government grant was slashed from £32.2 billion to £4.5 billion between 2009/10 and 2019/20, the overall amount councils are forecasted to gain from business rates in aggregate is only £17.8 billion in 2019/20 – not nearly enough to keep pace with demand for services. In fact, business rates have been falling as a percentage of GDP over the last decade, and the latest forecasts predict it will continue to decline (Figure 1). Plans from 2021/22 to allow councils to retain a greater proportion of business rates income in aggregate will be insufficient to keep up with demand.

Figure 1: Business rates income has been declining as a proportion of GDP

Annual business rates current receipts as a proportion of GDP, historical and forecast, 2008/09 – 2024/25

Source: HM Treasury Budgets, various.

It is clear that the current system is not working to provide councils with sufficient income overall. The way taxes are levied and redistributed is exacerbating the problem, allowing a few councils to gain from runaway growth in business rates income whilst the majority do not have enough to provide vital basic services. Both council tax and business rates are in need of significant reform, and our forthcoming report will present a full package for reforming them both. However, in advance of our final recommendations this blog discusses the possible reforms to business rates in particular, and some of the options to radically overhaul the present system.

A key focus of our research and policy development has been on how land value taxes (LVTs) might be used to replace some or all of business rates. Such taxes have had both recent and historical appeal.

The basic idea behind a land value tax is that pieces of land get their value from their location rather than the quality of the development sitting on top of them. What gives the location its value is the surrounding infrastructure – land tends to be more valuable in the centre of a city with high footfall, or areas with good transport infrastructure, schools, hospitals, and so on. This infrastructure has not been paid for by the landowner, but rather generations of taxpayers. Therefore in economic theory, land value tax is seen as an attempt to capture value that has nothing to do with the owner’s efforts, to reimburse society.

We discuss the arguments for and against such a tax, and in comparison to both current and hypothetical property taxes, in more detail in our forthcoming report. But economists have been calling for land value taxes since Adam Smith and the beginning of modern economic theory, because of the advantages in terms of taxing rentier wealth (rentier wealth is wealth gained from simply owning an asset, such as land) rather than productive investment (eg investment in productivity enhancing property). The idea also gained modern political salience in the UK with commitments from three opposition parties in 2017 – Labour, the Liberal Democrats and the Greens – to at least consider proposals.

Under the current business rates system, businesses occupying commercial property pay a levy on the so-called ‘rateable value’ of the property, an estimate of its open market rental value at the point of valuation (the most recent was in 2015). Small businesses (usually defined as those in a property with rateable value under £51,000) pay a slightly lower rate of 49.1% and larger business (rateable value over £51,000) pay 50.3%. Business rates are a property tax, but at the moment, businesses are implicitly taxed on the value of the land as well, since the value of the property and land is combined in the rateable value.

To support businesses who are struggling, the system includes a complicated series of discounts, exemptions and reliefs, such as the empty property discount which allows properties to remain empty without paying tax for three to six months. Other notable discounts include reliefs for the lowest value properties (those with a rateable value under £12,000-£15,000), for high street retail, and for charities.

Table 1 below shows a range of illustrative, high level revenue raising options for replacing current business rates, either with a land value tax or with a hybrid taxation that separates out the value of land and commercial property and taxes them separately. These options cover only the plots of land underlying properties currently eligible for business rates. We preserve existing discounts and exemptions, with the exception of the empty property discount (as this might incentivise landlords to avoid renting out their properties to avoid the tax), although these could be redistributed to protect those most in need under the new regime.

For our hybrid option, the balance between land and property taxation could shift over time, and a hybrid could also be a step towards implementing a full LVT. All options below simply consider land currently occupied by commercial property (ie the current tax base), but this should be expanded to include undeveloped land with planning permission – which would improve the economic efficiency of the tax, as well as increasing receipts.

Packages 1a and 1b show options for replacing business rates fully with a land value tax. In order to raise over £4 billion, a rate of 3.6% tax on the capital value of commercial land would be required, and in order to raise over £5 billion, a 3.8% tax on the capital value of land would be required. These are high rates, equivalent to 72%/75% respectively on the annual rental value of the land. The rates are high because by considering land alone rather than land and property together narrows the tax base.

Packages 2a, 2b, 3a and 3b show options for a hybrid land value/property tax. These would involve separating out the value of land and property, and paying separate levies on each. Packages 2a and 2b show that just over £4 billion/£5 billion could also be raised with a 2.8%/2.9% tax on the capital value of land, and a 51%/52% rate property rental values. These options present a uniform property tax multiplier (ie the same rate is paid regardless of the rateable value). Packages 3a and 3b present the same option, but ensuring that the small business multiplier is not increased and only the standard multiplier is raised. An infinite array of similar options could be generated which could raise similar revenue.

Table 1: revenue raised at various rates for options for replacing business rates in 2024/25

|

Description of policy package |

Current system |

Package 1a |

Package 1b |

Package 2a |

Package 2b |

Package 3a |

Package 3b |

|

Land value tax rental rate |

- |

72.00% |

75.00% |

56.50% |

58.50% |

56.50% |

58.50% |

|

Equivalent land value capital rate* |

- |

3.60% |

3.8% |

2.8% |

2.9% |

2.8% |

2.9% |

|

Property tax rates: |

|||||||

|

Small business multiplier |

49.1% |

- |

- |

51.0% |

52.0% |

49.1% |

49.1% |

|

Standard multiplier |

50.3% |

- |

- |

51.0% |

52.0% |

51.7% |

53.1% |

|

Revenue raised in 2024/25** |

- |

£4.4 bn |

£5.5 bn |

£4.4 bn |

£5.5 bn |

£4.4 bn |

£5.5 bn |

Source: NEF calculations using MHCLG data, various and Corlett, A., Dixon A., Humphrey, D. & von Thun, M. (2018). Replacing business rates: taxing land, not investment. See notes/appendix for details of method.

To estimate the packages above, we draw on methodology developed in Corlett, A., Dixon A., Humphrey, D. & von Thun, M. (2018). Replacing business rates: taxing land, not investment, in particular estimates of land value as a proportion of current rateable value generously shared with us by the authors.

A key question is the affordability of any reforms for businesses. Despite the discounts and exemptions, many businesses point to business rates as a key source of financial stress, and rates are unpopular. But this is in large part caused by infrequent property revaluations which cause large changes to bills: these occur only every five years or so, and therefore rates paid by businesses can jump massively if this has risen significantly in value (this was particularly a problem for high street retailers in the south in the most recent 2015 revaluation). Therefore, any new system should introduce more frequent revaluations, ideally on annual basis. Nevertheless if we replace business rates with a higher tax, it may indeed cause affordability issues for some.

In all the reform packages set out above, we argue that a land value tax should be levied directly on landlords rather than occupiers. However, this cost could be passed on to occupiers in the long term. Economic theory suggests that current high business rates bills have in fact been passed on to landlords, in the form of lower rents for businesses. The reason for this is that higher business rates will reduce the amount that businesses are willing to pay to rent a property, and a business owner always has the option to move to smaller/less expensive premises or moving the business online. Whereas the owners of the property have little else they can do with the property (leaving it empty would mean they got no rent at all and if they sell it the new owners would be in the same position – and so the sale price of the property would be commensurately lower anyway). Therefore landlords have no choice but to accept lower rents. To the extent that the current cost of business rates ultimately falls on the landlord in lower rents, we might also expect rents to rise faster in the long run to also offset the new direct tax on landlords, depending on the nature of the commercial renting market and the ability of landlords to absorb the costs.

Table 2 below presents the maximum likely change to bills for landlords, business owner/occupiers and business renters. We consider these different stakeholders with respect to size and geographic location, comparing a small retail property in the north west with a large retail property in the south east.

For businesses owning their own property, the impact on bills depends on the proportion of land value as opposed to property value in determining their property’s rateable value. Where land value is low as in example 1 below, business owner/occupiers will actually gain from a switch to land value tax. But where it is high, as in example 2 below, business owner/occupiers will face increases to their bills.

Although owner occupiers represent a minority of business owners, a proportion of the money raised through the abolition of the empty property discount could be used to compensate businesses against all or part of their losses.

For landlords and business renters though, the picture is slightly less clear. Business renters may enjoy decreases in their bills as a result of not paying business rates up to the maximum levels as presented below, although in the long run, landlords will likely pass back a large proportion in bills in the form of increased rents. A top-slice of preserved discounts and exemptions existing currently in the system (worth in excess of £4 billion) could be used to fund this in a revenue neutral way.

It should also be noted that, although in the short term there may be some adjustments over rent as landlords pass back some of the statutory incidence shift, in the long-run business renters will be more protected against increases if rates are raised on landlords. Under the current system, although increases are passed onto landlords in the long-run in the form of depressed rents, this may involve short-term pain. But under a land value tax, rates will impact landlords immediately and directly, protecting businesses from sharp changes to their bills.

Table 2 — Impact on bills — change in annual bill, 2024/25, compared to baseline, under our six packages

|

Policy package |

Package 1a |

Package 1b |

Package 2a |

Package 2b |

Package 3a |

Package 3b |

|

Small retail property in the north west (1) – current annual business rates bill £10,580 |

||||||

|

Change to bill, landlord |

£ 8,262 |

£ 8,606 |

£ 6,483 |

£ 6,713 |

£ 6,483 |

£ 6,713 |

|

% change to bill, business owner/renter |

-100% |

-100% |

-52% |

-51% |

-54% |

-54% |

|

% change to bill, business owner/occupier |

-22% |

-19% |

9% |

13% |

8% |

10% |

|

Large retail property in the South East (2) – current annual business rates bill £36,581 |

||||||

|

Change to bill, landlord |

£ 44,244 |

£ 46,087 |

£ 34,719 |

£ 35,948 |

£ 34,719 |

£ 35,948 |

|

% change to bill, business owner/renter |

-100% |

-100% |

-85% |

-85% |

-85% |

-84% |

|

% change to bill, business owner/occupier |

21% |

26% |

10% |

14% |

10% |

14% |

Source: NEF calculations using VOA stock of rateable value data.

We believe that swapping business rates for a land value tax not only brings the economic efficiency improvements of taxing wealth from simply owning an asset over productive investment, but also has the potential to raise revenue for councils and plug the local authority funding gap.

Download the technical appendix

Image: Marc Barrot (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Topics Housing & land Public services